It started, as love stories so often do, over an argument. The pair ambled out of Macon, Ga.’s Douglass Theatre on an early Saturday afternoon; her, Zelma Atwood, 16 years old, pretty yet fiery; him, Otis Redding, 19, dashing, charming, a lover with an ambitious streak. He’d just been performing with local star Johnny Jenkins at the town’s hip teenage hangout, the Douglass’ Saturday matinee – he wasn’t the star of the show just yet, although that wouldn’t be too far away – and, at some point during the performance, he caught Zelma’s eye. Zelma doesn’t remember – or won’t say – what the argument was about, but it doesn’t matter. “We met, we fell in love and then we married,” Zelma recalls over 50 years later. “It’s as simple as that.”

To understand Zelma Redding is to understand Otis Redding. The two have been intertwined since they first met on that fateful afternoon in 1960. When Otis was alive, Zelma was the one he would confide in on whispered, late-night phone calls from the road; after his 1967 death, it’s she who has kept a hawkish eye on his legacy, protecting the name of the man she loved so much.

Born on Oct. 7, 1942, in Macon, she lives there still, residing on the Big O ranch Otis bought when he first started tasting real fame in 1965. Otis loved animals, so the place was teeming with cattle, pigs, horses – “the whole big farm thing,” as Zelma puts it – until about two years ago when, due to her leg amputation, she became more concerned with maintaining the property than actually farming it. “We got a pretty open field out there, so you can just look,” she says. “Just sit and look.”

Sitting and looking wasn’t something Otis ever did too much. The pair’s relationship coincided with his rise to fame; frequently out touring or recording, even when he was in town it was mostly business. It was a tight relationship, although one that must have been caught in snatches, in fleeting visits.

“Otis wasn’t at the ranch a whole lot,” Zelma recalls. “He was very busy, just beginning to get situated. He’d go out Thursday to Sunday, come back and work in the office until Tuesday, and then go back out.”

“Even after [we started seeing each other] he went to California and did his first record [1960’s "She’s All Right"] and stayed with his uncle out there for about nine months. He said he was going to pursue his career and come back. And he did, because when he came back we got married.”

After their marriage in 1961, Zelma stayed in Macon taking care of their young family; Dexter came first in 1960, preceding the marriage, followed by daughter Karla and son Otis III. She’d often glimpse Otis on TV, performing for increasingly larger and more enthusiastic crowds; his albums began to sail up the charts, the hits – "These Arms of Mine," "I’ve Been Loving You Too Long (To Stop Now)," "Try a Little Tenderness" – started flowing. His hard work away from home was paying off.

“It was a great feeling, you know,” she says, with a smile. “He was such a humble person and so appreciated what was going on because -- artists back then were so different from artists today -- they was doing it for the love, they had so much respect for their bands and family and friends and people in the music business."

“He just accepted it, that he had to be gone. I just took it as it came. One day at a time.”

That Otis Redding’s career – and, moreover, life -- ended as soon as it did is one of popular music’s greatest tragedies. On the cusp of superstardom, with a startlingly energetic breakout performance at the Monterey Pop festival just behind him and what was to be his biggest single, "Dock of the Bay," just ahead of him, he took one flight too many. On Dec. 10, 1967, a small plane carrying Redding and his band mates took off into fog and heavy rain, destined for a show in Madison, Wis. It never made it; shortly before landing, the plane plunged into the icy waters of Lake Monona. Only trumpet player Ben Cauley survived – Redding’s body had to be pulled from the bottom of the lake the next day.

It was a loss so sudden, so unexpected and so traumatic that, even 45 years later, it still resonates.

“A tragedy like that you never, ever get over,” Zelma says.

“Not until this day. I live Otis Redding. That’s my life.

“At the time, you know, you’re looking for him to call, you’re looking for that gate to open … you’re just looking for everything that happened. You’re waiting for him to come home. It takes a long time for it to sink in.”

Zelma looked inward, turning her focus on herself and the couple’s three young children. It’s where it stayed over the next few, hard years; even today, the tight bonds formed in the immediate years after Otis’ death still hold true.

“We’re a strong family, and that’s what it takes to get over things that happened to your loved ones and stay together,” she says.

“I raised them to let them know that their father lost his life doing what he loved. And it was a great loss … we appreciate each day, every day we look at something and say, ‘Otis did that, Otis did that.’ It keeps you going.”

“I had to learn to teach them not to dwell [on his death] any longer. There’s too many other things, great things, great memories, that I could tell the kids about. It makes it easier to accept. Every day of my life, somebody’s going to say, ‘You knew Otis Redding’ – and I did know Otis Redding, so, it’s just a thing that won’t ever go away. Not in my lifetime.”

Gradually, she turned her attention to Otis’ business affairs. Over the years it’s been a long, constant vigil, not only having to fend off the usual unscrupulous suspects looking to profit from a dead superstar’s estate – rip-off artists, songwriting claimants and the like – but attempting to work around something even harder to pin down: technology.

Problems with the unauthorized use of Redding’s work mirror those that many other popular musicians in the late 20thcentury have dealt with. First emerging in the ‘80s, sampling was an early issue; later, in the 2000s, illegal downloading became an even more serious problem.

“It’s so hard to keep up with,” she says. “The thing with technology is trying to get a hold on it; by the time you think you’ve got a grip on something, something else has popped up. It’s going to be a long, long story. We tend to search and find stuff that’s not just right and, when we find it, I’ll call my attorney and let him know. Some we can control, but most of it is just out of our control.”

Of course, with an estate as big as that of Otis Redding there’s bound to be a multitude of people attempting to cash in.

“To this day everybody has trouble with songwriters, record companies and the like,” she says. “You’ve got to stay on top of your game. Back then they weren’t making as much money as they do today, so you got to fight, to maintain and stay strong and believe he lost his life for this -- and I’m not just going to let it go away. And that’s what I’m going to do – some people say I’m a little bit crazy, but I have to get my point across.”

Zelma clearly isn’t crazy. When riled, though, she can certainly be fierce. Author Scott Freeman discovered this to his detriment when his 2001 book "Otis!: The Otis Redding Story" raised her considerable ire. Although critically well received, the book’s assertion that Otis considered divorcing Zelma before his death, plus hints that Otis wasn’t always the teddy bear he made himself out to be back in Macon, didn’t sit well with the family at all. Over a decade after its publication, Zelma’s still furious.

“That Scott Freeman book, that’s a no-good book,” she says, with fire in her voice. “Shoddily done, just say anything … he went around and talked to different people who said they knew Otis but didn’t."

“Losers round here in Macon, they say anything. It’s so great for a person to die and hear very few bad things about them, because nobody lives a perfect life … with anything bad you hear about Otis, it’s somebody involved with him where his career took off and theirs didn’t. Jealous-streaking people.”

Such was the family’s distaste – and influence – that the book wasn’t carried in downtown Macon’s now-defunct Georgia Music Hall of Fame. “It boggles my mind that a book detailing the story of how Macon became almost the epicenter of the R&B, rock 'n' roll and funk movement is not carried by the Georgia Music Hall of Fame,” an upset Freeman fumed to Creative Loafing magazine in 2002.

Over the years Zelma has turned down various "authorized" book projects and at least four potential film treatments, although she now says there are plans for both in the works. “The thing is, it’s got to be done right,” she says. “My thing is that you don’t rush and do things. But don’t worry, we’ll get it done.”

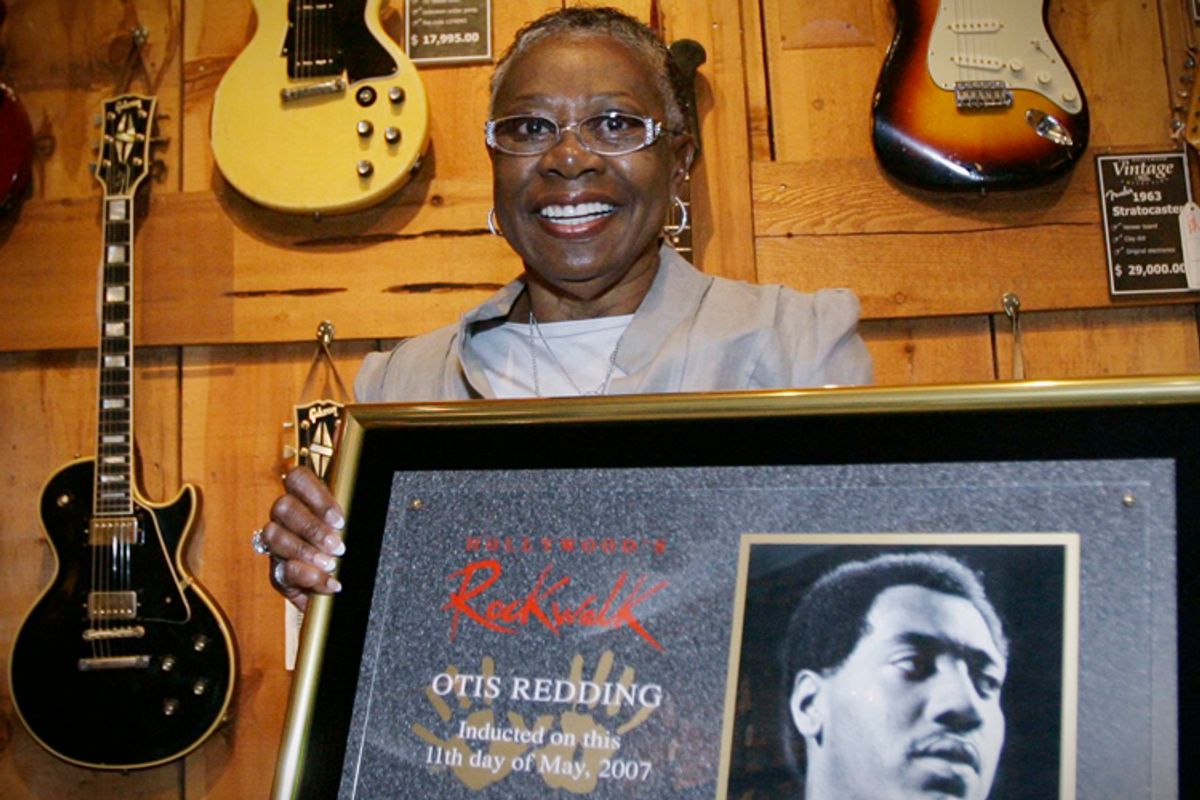

In 2007, she established the Big “O” Youth Educational Dream Foundation, now the Otis Redding Foundation. Created in Otis’ memory to help assist talented youths in the arts, the Otis Redding Foundation offers scholarship opportunities and holds a camp every year for around 30 to 35 young musicians to hone their singing, songwriting and general music skills. Although she no longer runs it – that’s left to her daughter, Karla Redding-Andrews – Zelma is still president of the foundation’s board of directors, keeping, of course, an ever-present eye on proceedings.

The foundation’s small office is situated a little off the main drag in downtown Macon, only three blocks from the old Douglass Theatre where it all started. It’s bright and colorful inside, decorated all around with mementos of Otis: paintings, album covers, the odd signed publicity shot of him staring straight into the camera with that famous, oh-so-charming smile. On this icy, grimy Georgian afternoon, Zelma sits in the center of the room, thoughtfully listing off her personal Otis Redding favorites. Otis, in a score of different guises, looks on from around the room.

“It’s so hard for me to pick just one,” she muses. “'These Arms of Mine,' 'My Lover’s Prayer,' 'Dreams (To Remember),' oh, I can go on and on. I put Otis Redding on at home on Saturdays and let it play all day. You know, that’s my favorite: all of them.”

“But,” she adds, “I do love 'These Arms of Mine,' just the way he phrases it. Then I say ‘he’s talking to me.’ That’s what I tell myself. You know, I always thought everything he sang he sang for me.” She stops, and a smile creeps across her face. “But now I’m being biased, aren’t I?”

Shares