I think it's fair to say that the 113th Congress has been marked by more failures than successes, but where it has succeeded it's been thanks to the relative (repeat: relative) functionality of the Senate.

When internal GOP strife has paralyzed the House, Republican senators -- emancipated from the gerrymander and the pressures of biannual elections -- have managed to forge necessary alliances with Democrats and pressure the lower chamber into action.

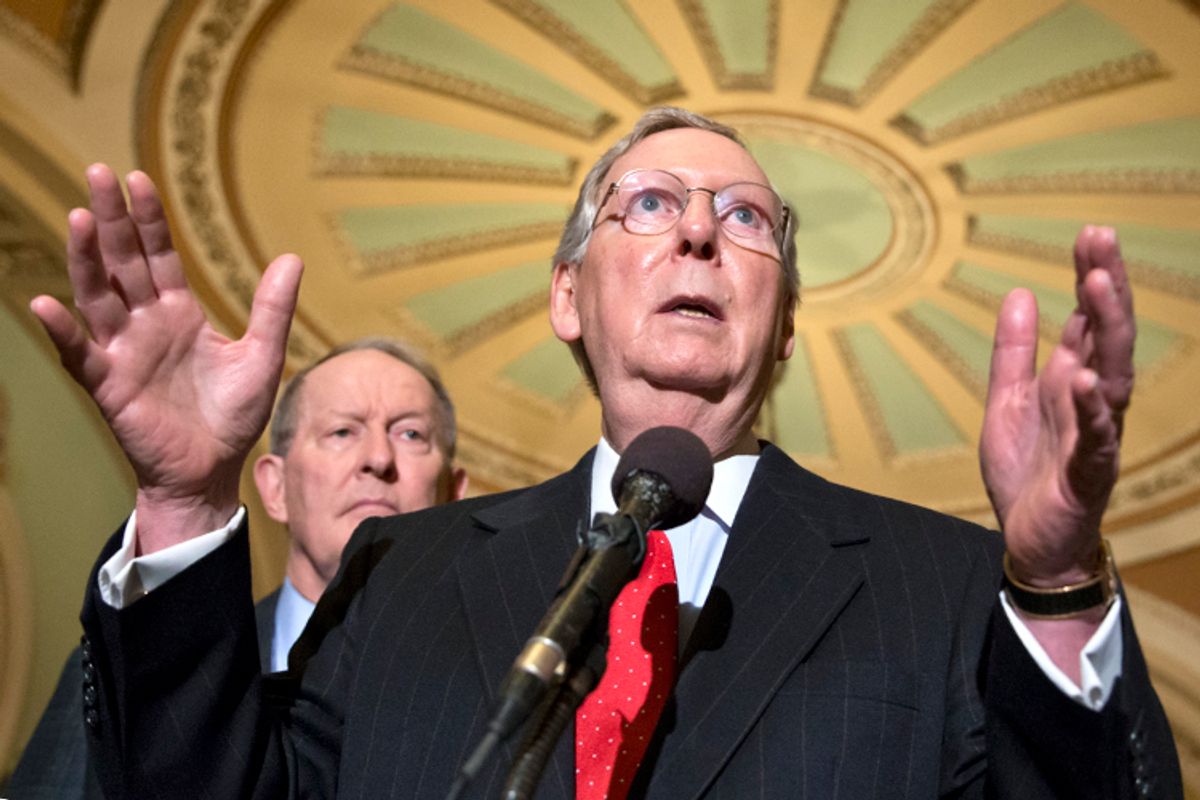

But right now we're witnessing a dramatic role reversal, which could threaten passage of a crucial budget bill, and underscores the delicate balance Senate Minority Leader Mitch McConnell must strike between his leadership responsibilities and his political obligation to defeat his primary challenger, Matt Bevin.

The Bipartisan Budget Act, authored by Rep. Paul Ryan, R-Wis., and Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., passed the House overwhelmingly on Thursday -- 332-94. Only 62 Republicans voted against it. So great was the imperative to prevent a GOP revolt that House Speaker John Boehner broke his silence and excoriated the conservative pressure groups that have been trying to defeat it and thus invite another government shutdown.

And in the end, it will probably pass the Senate, too. (While Sen. Dick Durbin said on Sunday that there were not yet enough votes to overcome a filibuster, Republican Ron Johnson came out in support of the bill, and many observers expect it will ultimately pass.) But it won't be by the safe margins we're used to.

The bill is in relative limbo for several reasons, but chief among them is that McConnell can't affirmatively whip for or against it. He's personally opposed to the legislation, supposedly because it eases sequestration's budget caps, but you don't have to be Sherlock Holmes to suspect that his primary challenge is motivating his opposition, too. At the same time, he doesn't oppose it so strongly that he's willing to kill it with a filibuster. He knows that if it dies, there's a strong chance that the government will shut down again, and he's vociferously opposed to letting that happen again.

So he's in a familiar bind. "Vote no, hope yes." His whip, Sen. John Cornyn, R-Texas, faces the same conundrum.

Suddenly John Boehner is the adult figure in the Republican leadership. By uniting in support of the bill, and taking outside interest groups head-on, House GOP leaders offered their members protection from transgressing against the right. They created a human shield around their vulnerable members. McConnell, by contrast, created an every-man-for-himself environment in his conference. The leadership void has produced a dangerous collective action problem. It's in the party's interest for this bill to pass, but absent a guarantee that a large number of Republicans will vote yes, it's in the interest of each individual Republican to vote no.

And the no votes -- including a number of reliable deal-makers -- are lining up. By Friday night, the list of nos and lean-nos included Sens. John Boozman, R-Ark., Jeff Flake, R-Ariz., Richard Shelby, R-Ala., Bob Corker, R-Tenn., Kelly Ayotte, R-N..H, Ted Cruz, R-Texas, Lindsey Graham, R-S.C., Tom Coburn, R-Okla., Roger Wicker, R-Miss., Mike Lee, R-Utah, Rand Paul, R-Ky., Marco Rubio, R-Fla., John Barrasso, R-Wyo., Richard Burr, R-N.C., and Dean Heller, R-Nev.

Exacerbating the problem, according to multiple Democratic and Republican sources, is the fact that the Senate GOP's top budget guy, Sen. Jeff Sessions, R-Ala. -- Paul Ryan's Senate counterpart! -- is whipping against the deal.

His main ground of opposition is as technical as it is political. Because the bill incorporates language from the Senate budget, it includes measures (called "deficit neutral reserve funds") that are designed to facilitate separate passage of specific spending priorities, provided they're paid for with tax increases or spending cuts. Under normal circumstances Senate Republicans would raise so-called points of order against Democratic tax-and-spend bills, and smother them in their infancy (waiving a budget point of order requires 60 votes), but if the Murray-Ryan bill passes, Republicans will be denied that option.

Any such legislation would still have to overcome a filibuster, so the concern isn't that Senate Democrats could force Republicans to pass tax increases. Rather, Sessions and others are worried that Harry Reid will use the budget bill to force Republicans to actively block popular bills that would be paid for by taxing wealthy earners.

National Review's Jonathan Strong was the first reporter to highlight this objection last week.

This may sound like a trivial distinction, and in some ways it is. Does it really matter which procedural tools Republicans use to block legislation? But the politics of a straightforward filibuster are harder to reckon with than the politics of technical objections like budget points of order. Which is to say, many Republicans want the Murray-Ryan bill to go down because they don't want to be subjected to tough votes in the future.

On top of all this, Senate conservatives don't like that the Murray-Ryan bill accomplishes much of its deficit reduction at the end of the 10-year budget window, and that it achieves billions in savings by cutting military pensions.

So, even if it winds up passing, it's not charging confidently out of the Senate.

Still, most, if not all, Democrats will vote for it. As much as they'd love to see Republicans shut down the government again, they want relief from sequestration and from crisis governing even more. The Murray-Ryan bill provides both of those things. It doesn't need overwhelming Republican support. But a handful of Republicans will have to join them. Those Republicans will draw all of the right's ire, along with McConnell for not doing more to sustain a filibuster. But he's damned either way. If too many of his members decide it's not worth the aggravation, McConnell might yet provoke the shutdown he's been so desperate to avoid.

Shares