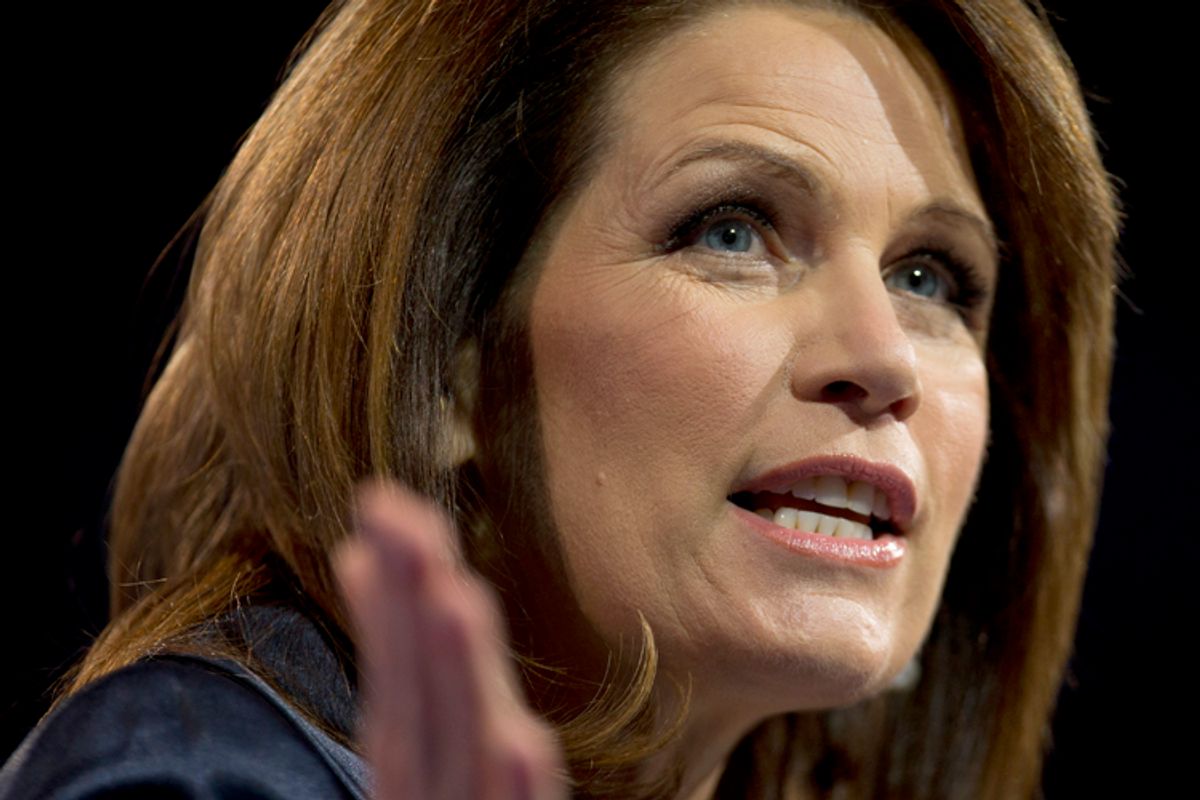

Last week, Michele Bachmann told a reporter that white guilt had helped elect Barack Obama, guilt that won't be a factor if Hillary Clinton is the Democratic presidential candidate in 2016. For this reason, Bachmann says she has high hopes for Republican success in 2016.

Bachmann is of course wrong. From exit polling, we know who voted for Barack Obama, and it wasn’t a wave of guilt-induced white people. In 2008, Obama won 43 percent of the white vote. In 2012, he won 39 percent of it. These are roughly the same percentages of white votes that Al Gore got in 2000 (42 percent) and that John Kerry got in 2004 (41 percent). As they typically do for Democratic presidential candidates, whites voted against Barack Obama by a landslide.

Obama rode to victory, not on the wings of white guilt, but on a swell of support from people of color. In 2004, 70 percent of people of color voted for John Kerry. In the 2008 and 2012 elections, that figure rocketed to 80 percent. This increased margin of support combined with an increased level of non-white turnout to deliver Obama decisive electoral majorities.

Although Bachmann may be confused on this point, the strategic leaders of the Republican party certainly aren’t. The darkening of the American electorate — and the decline in Republican power it entails — has been met head on with coordinated efforts to disenfranchise non-white voters and Democratic voters more generally.

Since 2006, Republicans have been passing laws to make it harder to vote almost anywhere they have a sufficient foothold to do so. This has included voter ID laws, restricting voter registration drives, ending same-day voter registration, shortening early voting and disenfranchising felons. Research from Keith Bentele and Erin O’Brien found that these kinds of “restrictive proposals were more likely to be introduced in states with larger African-American and non-citizen populations and with higher minority turnout in the previous presidential election. These proposals were also more likely to be introduced in states where both minority and low-income turnout had increased in recent elections.”

Moving outside of the electoral arena, Bachmann’s comments about white guilt are also remarkable because the phenomenon is surprisingly uncommon.

You might look at things like native genocide, black slavery, Jim Crow, the Chinese exclusion act and Japanese internment, and think that whites should feel guilty about it, but the surveys of racial opinion suggest they don't. Even though these historical events have helped generate the present world in which whites are, on average, wealthier and more powerful than people of color, most whites can’t be bothered and tend to think things are basically fine now.

In 2010, Pew asked people if they thought the country had done enough to give black people equal rights with whites. Just 36 percent of whites said more needed to be done, compared to 81 percent of African Americans. When asked whether black people face a lot of discrimination, 13 percent of whites answered in the affirmative, compared to 43 percent of black people.

This sort of racial disparity in opinion, in which whites downplay the significance of racism in society, shows up everywhere. Shortly after George Zimmerman's killing of Trayvon Martin, Gallup asked people whether they thought Zimmerman would have been arrested if Martin had been white. Seventy-three percent of black people said yes, compared to only 33 percent of whites who did so.

So, despite Bachmann's telling, white people aren’t wracked with guilt about race relations. The majority of them think everything is basically square now and will continue to think so even if you produce reams of data to the contrary. The white-guilt bogeyman of Bachmann and her ilk is not a serious theory of how whites think and act; rather, it — along with its close cousin of affirmative action complaining — is primarily a crutch used to explain away the success of people of color. It helps salve a dissonant mind that is forced to simultaneously contain within it the belief that people of color cannot succeed and real-world observations of them doing so.

Shares