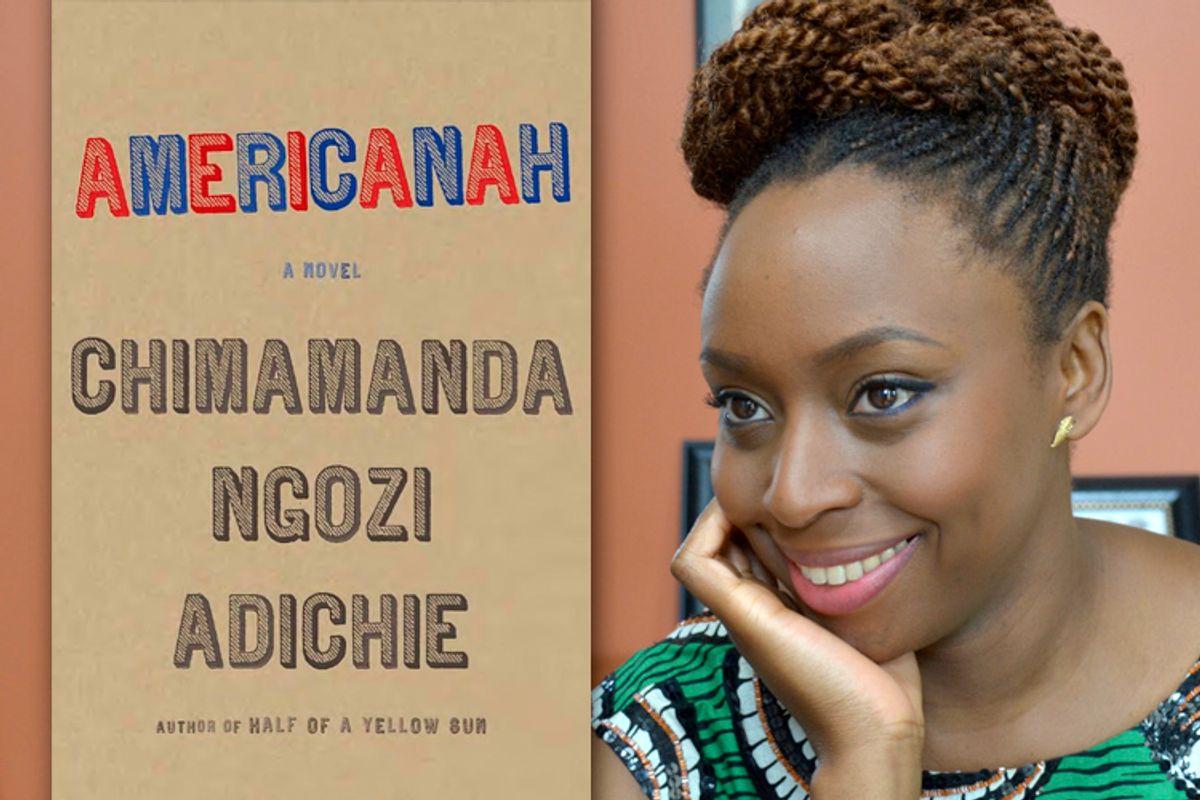

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie's 2013 novel "Americanah" crosses lots of borders. It spans three countries -- the U.S., Nigeria and London -- as lovers Ifemelu and Obinze meet, separate and meet again. But it also straddles the sometimes adversarial worlds of fiction and the Internet: entries from Ifemelu's blog, "Raceteenth or Various Observations About American Blacks (Those Formerly Known as Negroes) by a Non-American Black,” get prominent placement amid the action. Ifemelu comes from Nigeria -- where, she says, "race was not an issue" -- and "Raceteenth" chronicles her experiences in a country where it very much is.

"Americanah" is a National Book Critics Circle Award finalist and was named one of the 10 best books of 2013 by the New York Times, but Adichie's also gotten press lately for her social commentary. Beyoncé famously sampled her TED talk, "We should all be feminists." And in February, she wrote an open letter criticizing a new Nigerian law imposing stiff penalties for gay couples who marry or show affection publicly. Adichie spoke to Salon about "Americanah," the Internet and whether she's a political writer.

In fiction it can be difficult to capture other formats -- it's hard to include poetry in a novel and do it well, for instance. Did you find it hard to write Ifemelu's blog posts?

No. I actually had a lot of fun writing them. I would stop and laugh if I thought something was funny. I don’t blog, I’ve never blogged, but there was something about what I wanted to say and the voice in which I wanted to say it, and that particular kind of blog seemed like a great invention. There was a kind of immediacy to the blog and also I think that blogs can be idiosyncratic in a way that newspaper columns can’t be. I know that many blogs that I’ve seen are not quite like that, but I quite liked this particular kind of blog. I had a lot of fun.

Did you have models or specific blogs you were thinking about when you were writing those sections?

No, the blogs that I read were none that I really modeled this on.

I know some fiction writers try to stay away from the Internet when they’re working on fiction. Do you do that, or do you tend to stay engaged online when you’re writing your novels?

When it’s going well, no. When it’s not going well, I do all kinds of things. Actually, I do mostly online shopping when it’s not going well. But when it’s going well, I don’t read fiction; what I’ll do is I’ll read poetry from time to time. And usually, I’ll reread these things that I’ve read before. You know, I’ll pull out a book that I love and I’ll dip into it then I’ll go back to writing.

Do you have any favorite poets?

I’d say Derek Walcott.

"Americanah" has the feel of a global novel. It takes place in Nigeria and also in the U.S. and in England. Were any of those places harder to write about than the others?

Not really, no. The three places I know fairly well. But I think my knowledge of each place is different and, of course, built on my experiences in those places. I’ve never really lived in the U.K. I’ve visited many, many times; I have family there. Really almost everything in the novel I sort of took from somebody’s real story or from my own real story, but most of the U.K. stories are based on things experienced by other people.

The U.S. is different because it’s more familiar, because I’ve lived in the U.S. And so I was able to use some of my own experiences. Although I never quite used them the way they happened, you know; I sort of play with them. And Nigeria -- the later part of the book is familiar and the earlier part, not so much because I grew up here [in Nigeria]. I grew up in a small university town; I didn’t grow up in Lagos. That also was sort of an imagining too. A bit of an imaginative leap for me.

How do you decide if you’re going to write about your own experience or someone else’s experience. How do you figure out which experiences are OK to write about, and which are going to translate well to fiction?

I think my first general rule is that most of my experiences are not that interesting. It’s usually other people’s experiences. It’s not that entirely conscious. Somebody tells me a story or, you know, repeats an anecdote that somebody else told them and I just feel like I have to write it down so I don’t forget -- that means for me, something made it fiction-worthy. Interesting things never happen to me, so maybe two or three times when they do, I have to use them, so I write them down.

You’ve lived in Nigeria and in the U.S. How is literary culture different in those two places?

I feel like Nigeria is still -- in the 1960s and ‘70s we had this great, wonderful flowering of writing and then it went down during the dictatorship, so there’s something new about the writing that is being produced. It’s really in general about the cultural production, not just books -- it’s also music and art, fashion. There’s something exciting and new and fresh and so many of the people who are producing work are free to make new things because some things haven’t been made yet. I think, in the U.S. there’s a much longer tradition and so I don’t think there's that much -- "excitement" is not the word. It’s not new, it’s not like a new kind of flowering.

Several novels by African writers that have gotten a lot of press and awards in the U.S. in the last year. Do you think that the American literary establishment is taking more note of African voices right now?

Maybe it's that African stories told by Africans are now being published in a way that they weren’t 20 years ago. Twenty years ago, I think the few African stories that were published in the U.S. were usually not written by Africans and so I think that’s probably the major change. So it seems as though, all of a sudden, all of the Africans are popping out of the woodwork. But I think it’s a good thing and it’s quite lovely that there’s a growing diversity of African stories told by Africans.

How did you come to the decision to write your letter about Nigeria's anti-gay law?

It’s something I feel very strongly about. I think it's just a deeply unjust law. And I was very disappointed when it was signed into law. I’ve been talking to people and listening and I’ve wanted to speak up, but for while I felt almost numb from not just the popularity of the law, but what seemed to me to be a kind of willful blindness to what just seemed to me self-evident injustice.

People will talk about, "oh, you know, it’s a good thing because it’s in Africa and the Bible says …" and I’m just thinking, where is our compassion? It seems to me that on the subject of homosexuality, Nigerians -- who are usually very warm, really kind people -- just kind of switch off and lose something. And, so I just felt I had to. I feel so strongly, and also I know that I have a bit of a voice. I wanted to engage with Nigerians, in particular. The piece that I wrote has a specific Nigerian audience in mind because my hope is that if one person can start to think a little differently then maybe there’s a bit of hope.

What has the response to the piece been like?

I’ve had people say thank you to me. The best responses have been people that said they know somebody who read it and then sort of started rethinking. But of course there’s the people that have said to me, "We really respected you until we realized you’re a pawn of the West. And you’re only saying that because you get prizes from white people," and, you know, that sort of nonsense. But I expected that. There are people who’ve said I’m the devil.

[But] they haven’t been overwhelmingly negative, I have to say. Some people have said to me, "I’m still not convinced, but I did read what you wrote and I thought about it." I wanted to start a conversation and I think to start a conversation you do have to be respectful about people’s genuinely religious beliefs. And I think it’s very possible for them to have those beliefs and still be against the law because the law is unjust.

In general, do you feel that you’re a political writer?

I think I’m a political person; I’m a person who’s interested in politics. I’m interested in the way the world works; I’m interested in understanding it. I actually think of myself as a political student. "Political writer" always makes me sort of stop and think because, OK, what does that mean? And I think it makes me a little worried. Because it just seems to me, when you’re not a white male writing about white male things then somehow your work has to mean something. So people have said to me, "I read your first novel, it’s really a political allegory about Nigeria, isn’t it?" And I said, "No, it’s about a messed up family." So I always sort of want to step back when I hear that. But I am very interested in politics. I think of myself as a storyteller and I write fiction, but as a person living in the world who's very interested in politics.

You’re probably familiar with the VIDA count, the tally of how many female writers some publications feature, and how many books by women they review. Do you have any thoughts on that count, and whether it's an effective way to encourage equality in publications?

I suppose that’s one of the things that one can do, but I also think the way that the publishing industry works, in the U.S. and the U.K., there’s just a tendency to market and to approach books by men and women differently. And I think it goes a long way back.

I’ve always said, for example, Edith Wharton, in my opinion, is just as good a writer as Henry James. Now if we took out the cover of her book and put his name on it, many people would have called those books really marvelous and reinventing the glory of prose, that sort of thing, but she was female, and so it was just a good book. But Henry James was Jesus Christ. I also think that he’s a good writer; I just think they can both be equally good.

I think it still happens today. So if a man writes about the same subject as a woman, I think it’s edited differently, I think it’s marketed differently, I think the covers are different. It really does affect the way that it ends up going. So yes, it’s a good thing to talk about who’s getting reviewed, but I also think it’s important to talk about who’s being published and how are they being published. Are we putting a sort of lilac cover with a flower on the cover because it’s now girly and then are we making the man’s cover look like it’s just great literature?

Anything you want to say about "Americanah" that we haven’t touched on?

I have just been thrilled by how it’s been read. Because when I was writing it I thought, I’m still getting royalty checks from "Half of a Yellow Sun" so I can write this book that nobody will buy, but I’m just writing it for myself. And I’ve just been thrilled that it’s been read and I’ve actually been really surprised. Really, really surprised! I thought people would ban it and burn it or something, not review it. So, yeah, I’m actually really pleased.

Why were you so surprised?

Well, I thought because of the early readership. I had people read it early on and, you know, well-meaning people said to me, you should take out the blogs. I didn’t get much positive feedback. Only because most of these people were protective of me -- it was sort of like a "tone it down, make it easier to swallow" kind of thing. And I just thought if I do that then it’s not the book I want to write.

Shares