In the middle decades of the twentieth century, the United States experienced a meteoric rise in the rate of people earning four-year college degrees, as it soared from 6 percent of 25- to 29-year-olds in 1947 to 24 percent in 1977. During the next two decades, the percentage remained flat. In the mid-1990s, progress resumed but at a more modest rate; as of 2011, 32 percent of young adults had obtained bachelor’s degrees.

As recently as the 1980s, the nation was the undisputed international leader in the percentage of citizens graduating from college. The baby boomers, born in the decades immediately following World War II, pursued higher education in large numbers. Entering college during the late 1960s and 1970s, they swelled the ranks of college students and became the most educated members of their generation worldwide. In 2010, 32 percent of Americans between 55 and 64 held four-year college degrees, a higher percentage than citizens in the same age group in any other nation. (Norway claims a distant second place, with 25 percent of its citizens in that age group as college graduates.)

But among younger groups, the US lead has disappeared. In 2010 Americans between 25 and 34 had a college graduation rate of 33 percent, a mere one percentage point increase over the older generation. By contrast, young people in many other nations have catapulted over their American counterparts.

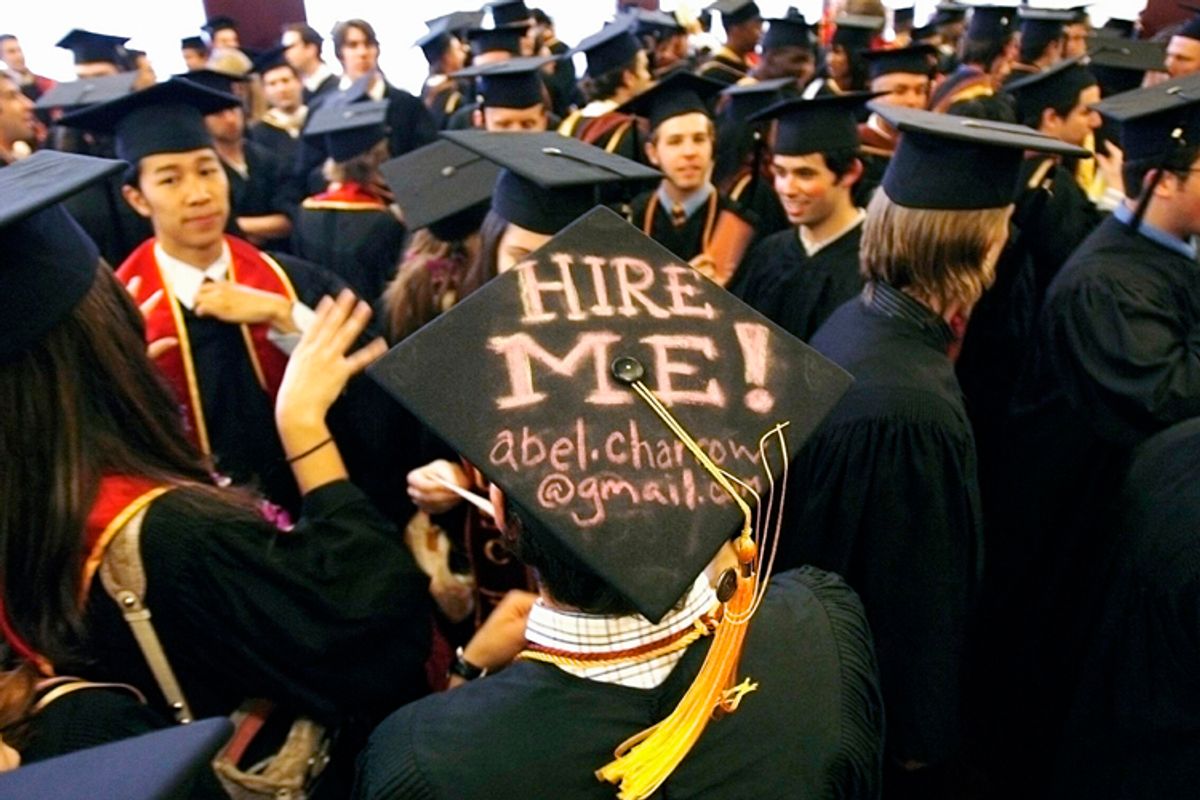

Those who claim that the United States is sending too many people to college discount these global historical trends, focusing instead on data points such as how recent college graduates have fared since the financial crisis in 2008. Yet in fact, while 6.8 percent of them suffered unemployment during this period, that figure pales in comparison to the 24 percent of recent high school graduates who were jobless. The recession accentuated a trend that has been under way for decades in the United States: the loss of good paying jobs for low-skilled workers and the increasing demand for highly skilled, well-educated workers. Since the early 1980s, this development has led to the so-called wage premium for those with college degrees. In 2010, among young adults between 25 and 40, those with four-year college degrees earned $40,000 on average compared to $25,000 for high school graduates. Moreover, the return from a college degree increases over an individual’s lifetime, with the gains in employment prospects and income being only the most obvious and easily measured benefits. one recent study focusing on income estimated that a four-year college degree pays an average return of 15.2 percent annually—far more than average returns in the stock market, at 6.8 percent since the 1950s; or corporate bonds, at 2.9 percent; or housing, at 0.4 percent. Those with higher rates of education enjoy better health and longevity. They participate in larger numbers in politics and civic life, making their voices heard in the public sphere and providing innumerable services to their communities. As economist Susan Dynarski testified to the US Senate Finance Committee in 2011, “A college education is one of the best investments a young person can make. even with record high tuition prices, a bachelor’s degree pays for itself several times over, in the form of higher income, lower unemployment, better health and enhanced civic engagement. Within ten years of college graduation, the typical BA will already have recouped the cost of her investment.”

However, not all college degrees offer these benefits. As we will see shortly, some institutions produce poor results for their students and interfere with what is otherwise a clear pattern of success. In the main, however, the evidence is quite unequivocal: the United States needs to increase the percentage of its citizens who attain college degrees.

If we look more closely to see who completes college today, we find that the ranks of college graduates reinforce income inequality. While we would expect that those from more affluent backgrounds are likely to attain more education than those who grow up poor, the extent of their advantage over the bottom three-quarters of the income distribution is striking. For those who grow up in high income families today, going to college is a routine part of life—like getting childhood immunizations—and the vast majority of such individuals, 71 percent, complete their bachelor’s degree in early adulthood. Among those in the upper middle income quartile, this same achievement, though more than twice as common as it was forty years ago, is still relatively unusual, reaching just 30 percent. Among Americans who have grown up in households below median income, the gains since 1970 have been meager: those in the lower middle quartile have increased their graduation rates from just 11 to 15 percent, and among those in the poorest group, from 6 to 10 percent. All told, degree attainment among upper income households so dramatically outpaces that of low and middle income people that the percentage who obtain diplomas among the top income quartile is greater than that of the other three quartiles combined. Our system of higher education not only fails to mitigate inequality but it exacerbates it, creating a deeply stratified society.

The unimpressive gains in graduation rates for most Americans have occurred despite the fact that access to college being admitted and then enrolling has improved dramatically over time, including among the least advantaged. Increasing enrollment is in part attributable to sharp increases in high school graduation rates, particularly among lower income groups, as many more now possess the necessary qualifications for higher education. In 2010, 83 percent of all 18- to 24-year-olds had earned a high school diploma or equivalent certification, and this included 73 percent of those in the bottom quartile, a nearly 20 percent improvement since 1970. Once individuals graduate from high school, most of them now continue on to college, 75 percent of 18- to 24-year-olds as of 2010. Here again, the biggest recent gains have been made in low income groups. Among students who enroll, however, completion rates by age 24 hover at only 47 percent. In effect, more students are starting college but they not graduating. Here economic inequality becomes apparent: nearly all of those from the highest income group who start college, 97 percent gain diplomas by age 24, a stunning improvement of 42 percentage points since 1970, compared to just 23 percent of those in the bottom quartile, a mere one percentage point improvement over the same period. Those in the second quartile fared little better, with only 26 percent reaching graduation by age 24; and even in the third quartile, just over half (51 percent) completed degrees in a timely fashion.

In short, completing college, or at least doing so promptly, eludes most young people from low and moderate income backgrounds.

Such outcomes may appear, at first blush, to indicate that our societal emphasis on the importance of college is misplaced. Certainly college is not for everyone and it should not be viewed as the only acceptable path following high school. The United States could do a far better job of linking those who are not college bound with jobs, a point made by James E. Rosenbaum in his insightful book, 'Beyond College for All." But others who criticize calls for increased college attainment insinuate that those who fail to enroll or fail to complete college are simply not motivated. “School bores and bothers them,” writes Robert Samuelson.

Richard Vedder claims that “college graduates, on average, are smarter and more disciplined and dependable than high school graduates.” Without a doubt, the nation could do better by those who do not have an interest in or aptitude for college. however, the implication that less advantaged students fail to graduate owing to a lack of motivation or incompetence misses the mark. When we look closely at the link between income and college graduation, we find that more is at play.

Certainly young people from higher socioeconomic backgrounds are typically better positioned to excel in the prerequisites for college admission and success. They are more likely to attend better primary and secondary schools. Their parents invest heavily in providing enriching extracurricular opportunities, including music lessons, travel, summer camps, and so forth. Not surprisingly, they earn higher grades and do better on standardized tests than those who grow up without such privileges. Yet scholars have found that even among individuals with the same academic credentials, those from less advantaged families are less likely to gain college degrees. Of students with high test scores, the vast majority from the highest income group graduate, while just over half of those in the middle income group and just a small majority of the rest manage to complete college. In fact, the college graduation rates of high-scoring low income individuals, at 30 percent, barely surpass those of low-scoring high income individuals, at 29 percent. Among students who enroll, attrition occurs most dramatically among those from families below median income. Clearly there must be something else going on here other than the weeding out of the unqualified and unmotivated.

In fact, ample evidence reveals that neither changes in college readiness nor shifts in the demographic characteristics of college students go very far to explain the unimpressive college graduation rates. A rigorous study by a group of economists, for example, found that rising tuition in public sector colleges bears most of the blame for this development. In addition, it shows that rising costs compel more students to work longer hours to finance their education, which makes it difficult for them to carry enough credits to graduate in a timely manner, if at all. Illustrating these trends, in 2013 students at Central Connecticut state university braced themselves for a 4.1 percent increase in tuition and fees—$19,897 per year for those who live on campus. Amber Pietrycha, a junior, already works two jobs per semester on average in order to make ends meet.

“Eight hundred bucks for me will bring it close to the line where I’m not entirely sure I could do it,” she said. Sophomore Salam Measho agreed, explaining that the increase “means I’m going to have to work more hours on weekends back home. That means less time studying. That’s too much of a strain on myself.” These developments are not inevitable, as demonstrated by a special program at the University of North Carolina Chapel Hill that provided extra financial support to low income students, and significantly boosted their graduation rates.

Not long ago, the United States led the world in promoting higher education for its citizens, spurring social mobility in the process. Many who grew up during the middle decades of the twentieth century became the first in their families to go to college. Many were assisted by generous GI bill benefits or Pell grants, and all had access to public universities and colleges with affordable tuition. Their lives were often transformed as they gained jobs, income, and opportunities to participate in public life that had been beyond the reach of their parents.

Today, however, the United States has evolved into an international outlier for its lack of such mobility. A group of researchers compared ten countries in terms of the quality of children’s lives on multiple dimensions-economic status, educational attainment, socioemotional well-being, and so forth—and found that in the United States quality of life was more determined by parents’ level of education than in any of the other countries investigated. In fact, the single most powerful relationship they detected was between the educational level of American parents and the subsequent level of education attained by their children: more than anywhere else, the vast majority of children fortunate to be born to highly educated parents acquired high levels of education, and conversely, the children of those with little education were penalized by receiving little education. They concluded that the United States is “the country with the least intergenerational mobility and the least equal opportunity for children to advance.” For those who are left behind, the consequences are severe. As recently as 1980, a male with a college degree earned about 20 percent more on average than one with a high school degree; by 2011, the difference had grown to 45 percent.

Citizens of the United States cherish the ideals of social mobility and opportunity that are widely associated with the “American Dream.” Many consider the chance to attend and graduate from college as both an end in itself—a manifestation of that ideal—and a crucial means toward its fuller realization over the course of a lifetime. In the middle of the twentieth century, federal student aid policies and public support of state-run colleges and universities helped make a college education possible for growing numbers of individuals across the income spectrum.

Now, more individuals than ever from every income group pursue a college education. But for most of those who do from the bottom half of the income spectrum, the effort proves futile. Their greatest obstacle to completing a four-year degree is not lack of ability or motivation, but insufficient financial support. As nearly all of those in the most affluent quarter of the population earn their diplomas in short order and reap the benefits of doing so, social stratification becomes more deeply entrenched.

For those who born into modest means, the gaps that separate them from the upper echelon grow increasingly insurmountable.

Excerpted with permission from "Degrees of Inequality: How the Politics of Higher Education Sabotaged the American Dream" by Suzanne Mettler. Available from Basic Books, a member of The Perseus Books Group. Copyright © 2014.

Shares