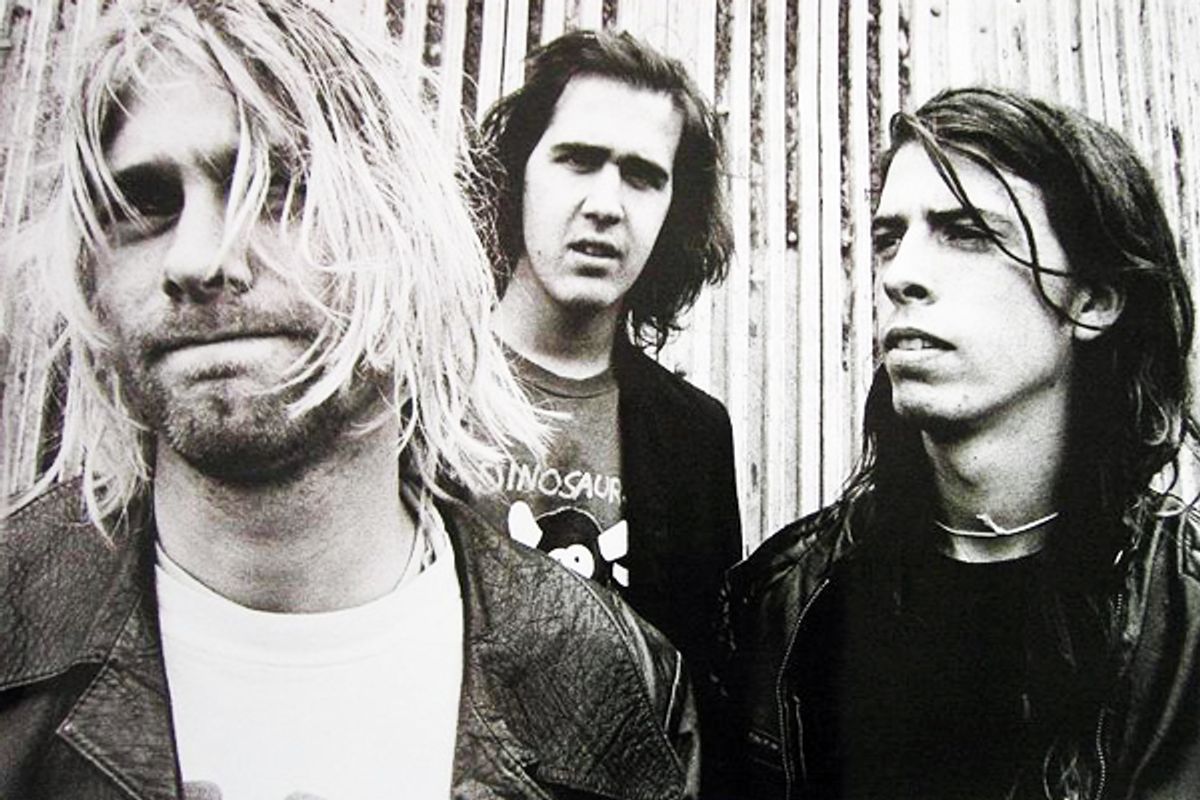

Kurt Cobain is now 20 years in his grave. Before his death at age 27, he was made the horse chosen to pull a very big bandwagon called grunge. As a descriptive term for music, grunge is vague at best. As a media-created social trend, it has no meaning at all. While Nirvana gets inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame tonight, let’s look at the fad that rode their coattails.

On Nov. 15, 1992, the New York Times published “Grunge: A Success Story” in its newly minted Style of the Times section. The piece strikes a tone of poised cynicism, describing the movement it is helping to manufacture with hip disdain: “This generation of greasy Caucasian youths in ripped jeans, untucked flannel and stomping boots spent their formative years watching television, inhaling beer or pot, listening to old Black Sabbath albums and dreaming of the day they would trade in their air guitars for the real thing, so that they, too, could become famous rock-and-roll heroes.”

There was even a sidebar containing a colorful lexicon of grunge-movement slang. Old, ripped jeans were called “wack slacks,” and hanging out was now known in hip parlance as “swingin’ on the flippity-flop.”

In its rush to write about a movement it could exploit but not endorse, the Times committed a major error: the “grunge-speak” glossary had been entirely made up by the young woman who supplied it, Megan Jasper. The Gray Lady had been played.

Thomas Frank (now a Salon contributor) revealed the hoax in the Baffler’s winter-spring 1993 issue and explained that: “Ms. Jasper was surprised by the various journalists’ ’weird idea that Seattle was this incredibly isolated thing,’ with a noticeably distinct rock culture. The result of this credulity was that, as Ms. Jasper puts it, ‘I could tell [the interviewer] anything. I could tell him people walked on their hands to shows.’”

By the late 1980s, the hair metal phase was about played out. Major labels were signing second-stringers; not everybody was going to hit like Bon Jovi. Then, according to MTV "120 Minutes" host Matt Pinfield, came a pivotal moment: “Because of Guns and Roses, and that record 'Appetite for Destruction' -- that was a gateway for bands that were heavier, that were dirtier, and that brought some of the original punk ideals into it.”

There is a standard narrative in the industry, generally agreed to be true: By the early '90s, Seattle’s Sub Pop label was circling the drain. At the same time, DGC Records, a subsidiary of industry giant Geffen, signed New York subculture icons Sonic Youth -- not only because 1988’s "Daydream Nation" was so terrific but because they provided DGC the credibility it needed to bring other alternative bands on board. Nirvana and Sonic Youth shared the same management team, and a deal was made. "Nevermind" was recorded quickly and released in September 1991.

The music industry is always looking for the Next Big Thing. By the time the New York Times published “Grunge: A Success Story,” the Next Big Thing had already happened. "Nevermind" had already knocked Michael Jackson off the top of the charts and went on to sell more than 30 million copies. The success of the album was so overwhelming that it ushered in a new gold rush the media dubbed grunge.

This led to another standard narrative -- that "Nevermind," and, more important, the tortured genius behind it -- singer, guitarist and principal songwriter Kurt Cobain -- brought punk into the mainstream. The problem was that punk is an ethos as much as an aesthetic, and couldn’t survive the selling.

Born in Hoquiam, Wash., in 1967, Cobain had long ago established his outsider identity by the late 1980s. To him, only the marginalized could make meaningful art.

“I like the comfort in knowing that women are the only future in rock and roll,” he wrote in his journal in the late 1980s. “I like the comfort in knowing that the Afro American invented rock and roll yet has only been rewarded or awarded for their accomplishments when conforming to the white mans standards. I like the comfort in knowing that the Afro American has once again been the only race that has brought a new form of original music to this decade.”

“Art that has long lasting value,” he wrote, “cannot be appreciated by the majorities.”

Nirvana released their first full-length, "Bleach," on Sub Pop in 1989. Soon tiring of the constraints of the coalescing grunge scene, the band released “Sliver,” a more accessible single. “I had to write a pop song and release it on a single to prepare people for the next record,” Cobain told Rolling Stone. “I wanted to write more songs like that.”

Here lies the little-known ambition of Kurt Cobain. Even as the band waited to sign to DGC, it was taking a different musical direction. “I was trying to write the ultimate pop song,” he told Rolling Stone in 1993. “I was basically trying to rip off the Pixies. I have to admit it.”

And so we have “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” the hit on "Nevermind" that propelled the album to diamond status, inspired an iconic video, and birthed a manufactured movement.

Trends are a part of the business, and we’d seen them before with movements like disco. There was even a brief scrum in the late '70s with punk (the Sex Pistols signed with EMI, for goodness’ sake!) but that flame-out happened in short order. Punk was decidedly against mainstreaming. A dozen years later, the kids like Cobain who took it to heart were no less opposed.

“For a few years in Seattle, it was the Summer of Love, and it was so great,” he told Rolling Stone. “To be able to just jump out on top of the crowd with my guitar and be held up and pushed to the back of the room, and then brought back with no harm done to me – it was a celebration of something that no one could put their finger on. But once it got into the mainstream, it was over.”

“Punk was anti-fashion. It made a statement,” James Truman, editor-in-chief of Details magazine told the New York Times in 1992. “Grunge is about not making a statement, which is why it's crazy for it to become a fashion statement.” By that time, designer Marc Jacobs had sent models out on the runway wearing wool ski caps as part of his spring Perry Ellis collection. He was hailed as “the guru of grunge.” Bands related mostly by their time zone were being lumped together. Even Kurt Cobain got caught up in it. When asked about his feud with Pearl Jam, another multi-platinum act associated with grunge, he said, “It was my fault; I should have been slagging off the record company instead of them. They were marketed – not probably against their will – but without them realizing they were being pushed into the grunge bandwagon.”

The fact is that so-called grunge bands actually don’t sound much like each other. It would be just as easy to compare Pearl Jam to Blues Traveler for their slight but shared hippy shuffle as it would be to put them next to Alice in Chains for the clenched-jaw vocals. If grunge means punk-and-metal-inflected sludge with distorted guitars, how do Nirvana’s nimble tempos and light-switch dynamics fit in? And what are we supposed to make of the massive success of their acoustic Unplugged album? “If you were a music fan, then you really didn’t give a shit because you liked the records for what they were,” Matt Pinfield says. “Especially if you liked the original punk ethos that said you could do anything.” (It should be noted at this point that Megan Jasper, the receptionist who fooled the New York Times with a list of made-up grunge-speak, is now the executive vice president of Sub Pop Records.)

Even though those behind a fad act as if it will go on forever, the death of a trend is important. It maximizes profit -- videos and singles actually being played to death, clothing lines designed and becoming passé, and a general saturation of product and image, leading to an inevitable backlash. Thus the stage is cleared for the next act, which, from a business point of view, is invariably a repeat performance. It is the American boom-and-bust economic model in microcosm.

By the mid-'90s, the media had perfected its craft. They sniffed around Chapel Hill, N.C., in the early part of the decade – some genius calling it “The New Seattle” – but apart from a couple of major label bidding wars nothing happened. That is, until the two least grungy Chapel Hill bands broke big: Ben Folds Five and my group the Squirrel Nut Zippers. Within a year, the Zippers had the Swing Movement boat anchor hung around our necks. This trend was an easier sell: The costumes were prettier and the music was happier. Apart from the Zippers’ DIY approach, punk was not much in evidence in the Swing Movement. Under Clear Channel, top-40 radio had consolidated as well, making the playlists more homogeneous. Above all, most of the bands involved wanted the trend to happen as much as anybody else: Brian Setzer rushed to cover Louis Prima’s “Jump, Jive an’ Wail” after it was featured in a Gap commercial and won a Grammy for it.

No matter: the Swing Movement didn’t last more than a couple of years. Despite all the effort, none of those records sold more than a fraction of "Nevermind."

In addition to his talents as a musician and composer, Kurt Cobain, it must be remembered, was hot. He was made the reluctant spokesmodel, not just for the boggling popularity of his band, or of the media-created movement (which he himself rejected), but also for his entire generation – an impossible role. After musing to Rolling Stone about John Lennon’s life becoming a prison, Cobain said, “That's the crux of the problem that I've had with becoming a celebrity – the way people deal with celebrities. It needs to be changed; it really does ... No matter how hard you try, it only comes out like you're bitching about it. Grunge is as potent a term as New Wave. You can't get out of it.” He didn’t, at least in the short term.

Whatever demons were chasing Kurt Cobain caught up with him, fatally, 20 years ago. He found longevity, though. Through uncompromising talent, he was able to slip the noose of fashion. He committed himself to his music and did good work -- work that may be of its time, but approaches timelessness.

“I think what he did still echoes with disenfranchised youth,” says Pinfield. “There are still young people who listen and still feel like outsiders. Now more than ever, because popular music has gotten so ... happy.”

Nirvana will undergo further institutionalization by being inducted into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame tonight. This involves its own level of bullshit, but no one is a saint until they’re canonized, and the Hall of Fame could have – and has – done far worse. “Like Jimi Hendrix and Jim Morrison, Cobain was 27, in his creative prime, when he died,” notes the inductee bio. “Also like them, he and Nirvana remain an enduring influence and challenge – proof that the right band with the right noise can change the world.”

This kind of copy makes for a beautiful tombstone. See how easily Nirvana fits into the canon: They never outlived their relevance, never put out a shitty synth record. Kurt Cobain is now installed in the line of succession of young dead geniuses and can’t say a thing about it. I agree with the Hall of Fame when they describe Cobain and Nirvana as an enduring challenge, though, and to my mind it is this: do what you do best and do it well, even when people think it’s too good to belong to you anymore.

Shares