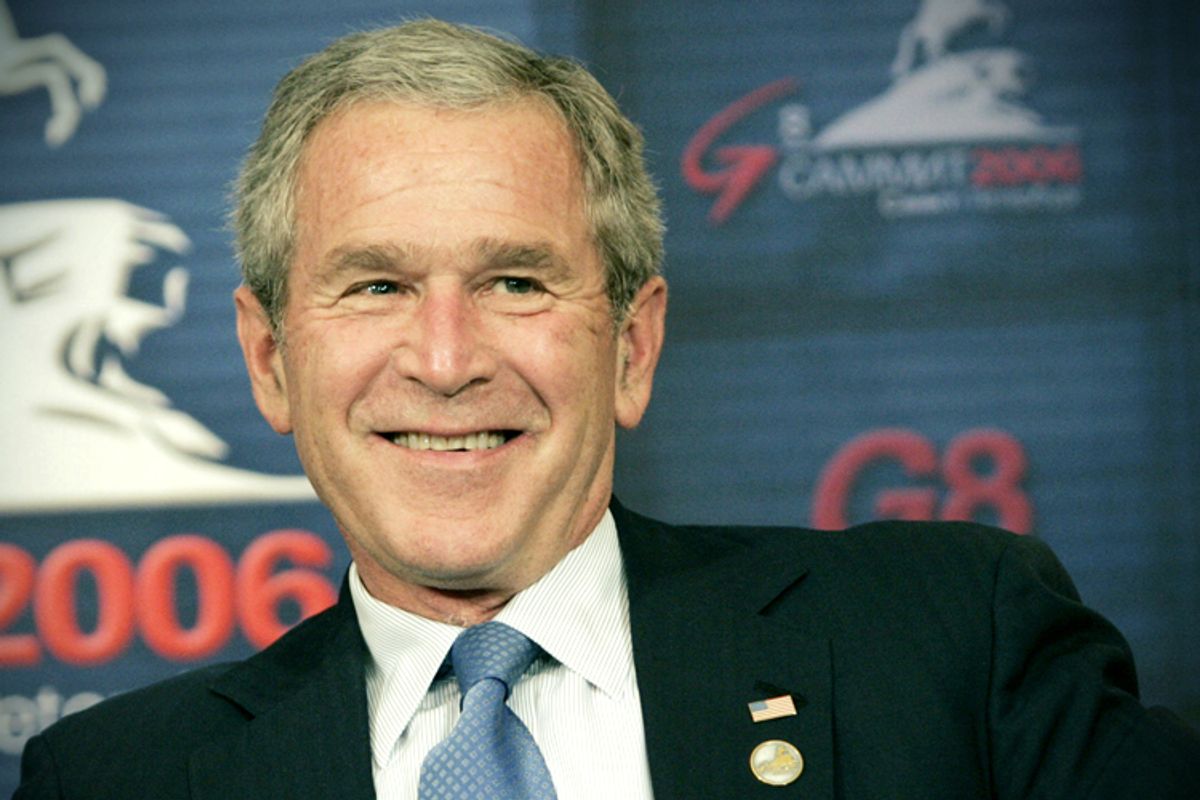

Former president George W. Bush is famous for his malapropisms, but there is one mangled word he did not coin. Impersonating then-candidate Bush during the election campaign of 2000, the comedian Will Ferrell mispronounced “strategy” as “strategery.” Although he didn’t originate the word, Bush lived up to its ironic implications, by diverting substantial numbers of U.S. military forces from Afghanistan, whose Taleban government had sheltered Osama bin Laden, in order to invade and occupy Iraq, a country that had nothing to do with the 9/11 terrorist attacks. While warning of the menace of Iran’s theocratic regime, the Bush administration removed one threat to Iran in Afghanistan and next removed the anti-Iranian regime in Iraq, on the advice of Ahmed Chalabi, an Iraqi exile trusted by Bush’s neoconservative allies. After the invasion, the invasion, turned out to have close ties to Iran. While pursuing closer ties with Tehran, the post-Saddam regime in Baghdad then said no to the permanent stationing of American forces in the country.

Could anything recall Bush’s wars in Iraq and Afghanistan to the benefit of Iran as examples of misguided “strategery”? The answer, it appears, is yes.

The Obama administration has responded to Russia’s annexation of Crimea, and its apparent promotion of secessionist groups in Eastern Ukraine, by announcing mostly minor sanctions against Russian individuals. In response, the Russian government of President Vladimir Putin has crippled what is left of the once-great American space program.

Russia will end U.S.-Russian cooperation in the international space station four years early, in 2020 instead of 2024. The Putin regime has the power to do so because, following the retirement of the last space shuttle, the only way that American astronauts can get into space is by hitching a ride aboard Russian rockets.

And that’s not all—the U.S. military is dependent on the Russian space program, as well as NASA. According to Vox:

The Atlas V rocket — built by a joint Lockheed Martin-Boeing venture and used to launch American military satellites and civilian payloads — runs on a Russian-built engine.

When the Atlas V was being designed in the 1990s, Lockheed Martin got a waiver from the usual Defense Department requirement that critical components be manufactured in the US, partly because the Russian engines were better and less expensive than American options, and partly because of political motivations.

Observers of American foreign policy often claim that the U.S. does not have a consistent grand strategy. That may be true. But no one can doubt that the U.S. has a consistent “grand strategery,” when it comes to outsourcing crucial U.S. military capabilities to the great powers that are America’s most likely geopolitical rivals.

China is widely considered to be the most formidable great-power rival or “peer competitor” that may come into conflict with the U.S. in the decades ahead. President Obama’s “pivot to Asia,” a bolstering of U.S. military support and trade ties with East Asian and Pacific allies, is generally seen as a not-so-subtle attempt to deter China from unilaterally asserting greater power and influence in its own region.

And yet China, in the last few years, has repeatedly provoked clashes with its neighbors—most recently, with Vietnam, over oil drilling rights in contested waters. What makes China think it can get away with these provocations, in the face of U.S. disapproval?

Well, one answer may be the fact that the Pentagon is using a Chinese satellite for communications with its African operations, according to Bloomberg:

The satellite’s services were leased under a one-year, $10.6 million contract through the government solutions unit of a U.S. company, Harris CapRock Communications. The Fairfax, Virginia-based unit is one of 18 companies under an established contract the Defense Information Systems Agency uses for specialized commercial satellite services.

While the Apstar-7 lease expires May 14, the agency has the option to extend it for as long as three more years.

That’s not the only example of the Pentagon’s dependence on Chinese industry. In 2011 it was discovered that some U.S. weapons systems are full of counterfeit Chinese-made semiconductors.

Theodore Roosevelt’s rule of strategy was “Speak softly and carry a big stick.” Lecturing your opponents and then asking them if you can buy or borrow one of their sticks is not strategy. It’s strategery.

Lenin would not have been surprised. Noting the eagerness of Western firms and investors to do business with the Soviet Union, he predicted that capitalists would sell the rope that the communists would use to hang them. The elites in Russia and China have abandoned Marxism for state capitalism, but true to Lenin’s policy they have no objections if the U.S. chooses to allow its own space program and defense industrial base to deteriorate, while becoming dependent on their factories.

Russia and China are practicing the art of strategy—not strategery.

Shares