Postmodernism did not begin with Don Johnson, but he is one of its principal avatars. Johnson’s performance as Detective Sonny Crockett in the style-shaping '80s TV series “Miami Vice” – he tells me, in a reasonably good accent, that the French title was “Un flic de Miami” – was good enough to be a little confusing, to send different signals to different viewers. On one level, Johnson was playing an updated version of Jack Lord in “Hawaii Five-O,” striking a pose in his voluminous period fashions from Hugo Boss and Ermenegildo Zegna, alongside that black 1972 Ferrari Daytona Spyder. On another, Johnson always appeared to be in on the joke, and not to take himself too seriously as TV’s biggest male sex symbol and star of its hottest show.

That same duality endures to this day, when Don Johnson is a colorful 64-year-old character actor with hilarious war stories, a guy who came through the crucible of fame and out the other side. He’s striking and entertaining in pretty much every role: As a thoroughly nefarious slave-owner in “Django Unchained,” as Kenny Powers’ no-account dad on “Eastbound & Down,” as Sheriff and/or Ranger Earl McGray on “From Dusk Till Dawn.” But being in on the joke is also a key factor in Johnson’s later career, which is built on the recognition that he is still “that guy from that TV show,” almost 25 years after it went off the air.

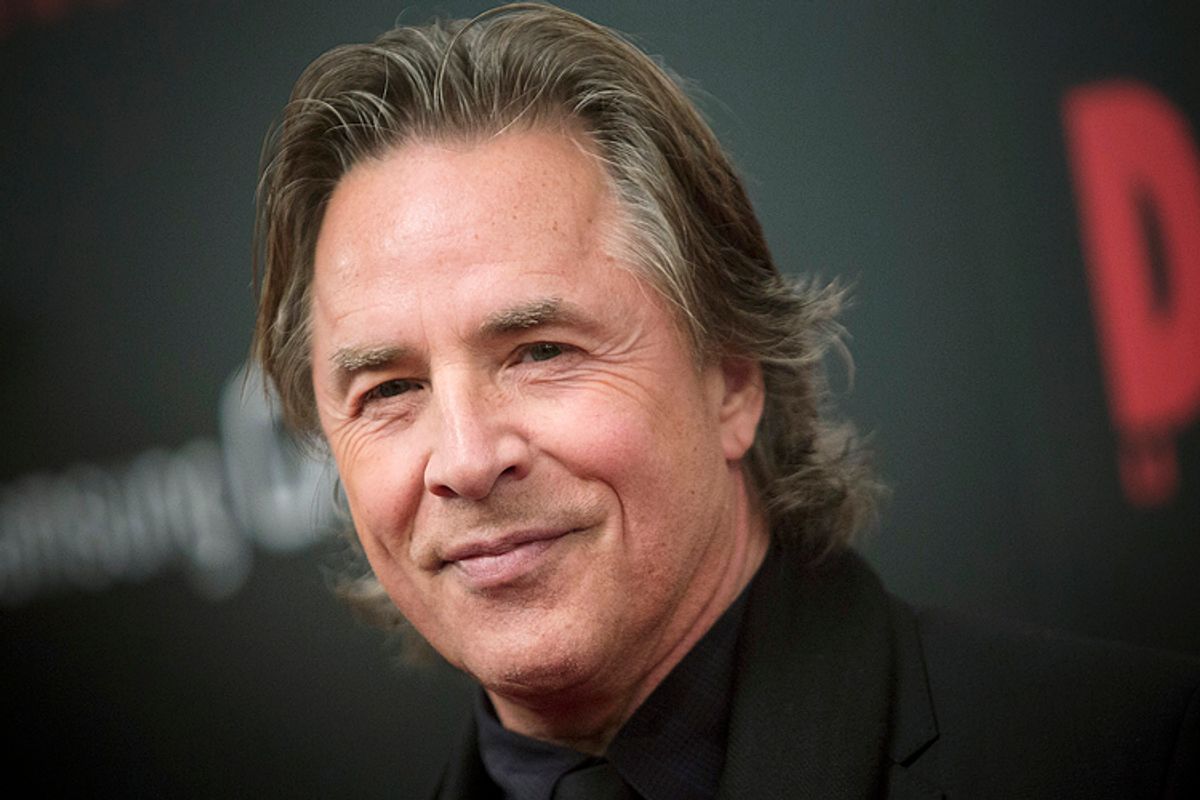

I got to split a fruit salad and drink espresso with Johnson recently in the venerable bar of the Carlyle Hotel on the Upper East Side of Manhattan, and he was the one who mentioned that this room was for decades the home of legendary cabaret entertainer Bobby Short. He was in town to talk about his role as a colorful Texas private eye called Jim Bob, who tries to untangle the deadly feud between Michael C. Hall and Sam Shepard in director Jim Mickle’s terrific neo-noir “Cold in July” (which I reviewed at Sundance), an adaptation of the late-'80s crime novel by Joe R. Lansdale. If it seems striking or unusual that the guy who plays a big-hatted, womanizing redneck also knows about Bobby Short – who was the very personification of a New York sophisticate – you’re beginning to understand Don Johnson.

As we discussed, Johnson was no kid when he landed his big TV role. He’d been bouncing around the acting profession for 15 years, ever since leaving the University of Kansas in 1969 for a gig at American Conservatory Theater in San Francisco. He moved from there to L.A. to New York to Paris and back again; he hung out at Andy Warhol’s Factory and was briefly roommates with Sal Mineo in West Hollywood before the latter was murdered. Johnson had numerous roles in forgettable TV episodes and small films, including playing the lead in the post-apocalyptic science-fiction movie “A Boy and His Dog,” which became something of a cult classic. Johnson played Elvis Presley in a 1981 TV movie, which may have put him on Michael Mann’s radar screen when it came time to cast “Miami Vice,” but for all intents and purposes he was a 35-year-old Hollywood unknown – just another good-looking guy whose time was running out – the first time he put on Sonny Crockett’s designer shades.

Half a lifetime later, sitting at the Carlyle bar in jeans and a T-shirt, he’s still Don Johnson. The waitress here no doubt sees famous people every day – David Gergen, neoliberal political apparatchik and advisor to four presidents, is having breakfast across the room – but is visibly trying to conceal her excitement. I tell Johnson I never got to see Bobby Short play the Carlyle, but I once saw Eartha Kitt in this room. She wrapped her feather boa around my neck at one point and sat in my lap (perhaps while singing “Santa Baby”).

“Did you really?” Johnson says. “Eartha Kitt did an episode of ‘Miami Vice’ with us once. She was a Haitian voodoo princess. I’m not actually sure how accurate it was, as a cultural presentation. Let’s say it was our version of voodoo.”

I’ve heard you say that “Miami Vice” was both a blessing and a curse. It must be funny to be associated with something that shaped cultural history to that extent.

Yeah, global cultural history. I just got back from Cannes yesterday, and so many people would come up to me saying [French accent], “Oh my God, Monsieur Johnson! You changed my life, in the way I dress, and the way that we move and talk.” In France it was called “Un flic de Miami.”

Right -- "A Miami Cop.” Which would be you, I guess. This is an utterly irrelevant tangent, but I’m from the Bay Area so I’m always interested. I had not realized that at one time you were a student at ACT in San Francisco.

Yeah, I was. I was hired right out of the University of Kansas. I studied during the day and they were paying me as a journeyman actor to do plays and repertory at night. That’s actually how I got trained classically to do theater.

So the late ‘60s and early ‘70s in the Bay Area – that must have been interesting! I can only imagine it. I’m sure you had a number of experiences you don’t want to tell a reporter about …

Listen, my life is pretty much an open book, but I told this story the other night. I was in San Francisco two weeks before I figured out who they were whistling at.

You had never been openly hit on by guys before, I am guessing.

I didn’t have a clue! I was from Missouri by way of Kansas. In San Francisco, well, let’s say it was pretty overt.

And not too long after that you moved to L.A. and got your first movie and TV roles, is that right?

I actually left San Francisco after about a year and went to L.A. to do a play, and then I got hired to do a movie right out of the play. It was my first film, which was a forgettable movie called “The Magic Garden of Stanley Sweetheart.” Roles were few and far between, so I had to go back and forth from living off my wits and whatever jobs I could pull. I actually started making some pretty good money; you know, making a living as opposed to sub-poverty level living as an actor. I started doing well, or well-ish, in my late 20s.

Sometime around there you made “A Boy and His Dog,” which was almost certainly the first thing I ever saw you in. I can remember going to see that with my mom!

Yeah, I was 22 when I made that. It was a good movie and it was made for nothing. I think we made that film for a quarter of a million bucks. I got a piece [a percentage of royalties], and, you know, after about 20 or 30 years, I got a check. It was for some insignificant sum, but I was floored. When I was poor and a struggling actor, I’d be chasing them going, “That film makes money! It plays in every goddamn place in the world! It plays every day in my life somewhere! How come I’m not getting any money?”

Well, as you know better than I do, they have accountants whose job it is to make sure that the movie never technically makes money.

I’ve heard of that. I’ve heard that exists.

So you had obviously had a lot of not just acting experience but also life experience, before “Miami Vice” came along.

When you commit to be an artist of any sort you commit to that life. This is not true for everybody, but more often than not, that commitment comes with a commitment to something that you love no matter what. So you’re going to take the good with the bad. And you’re going to struggle. But the funny thing is you are in there with a lot of other artists who are struggling, you network with people who are kind of going through the same things, some succeeding at various levels. Ed Ruscha [a prominent Los Angeles Pop artist] was a friend of mine back then and he was just starting to pop, you know. And of course I knew the Warhol bunch and Andy from my time in New York. There was an underground subculture of us artists that all kind of knew each other and recognized each other for our varying degrees of ability, I should say. There’s something exciting about it. There’s also a horrible, real side of it: getting thrown out of your apartment, trying to get to an audition when you don’t have a car. So you’re hustling all the time, trying to figure it out. You learn a lot and it’s a big life.

Wikipedia doesn’t say anything about your time in New York. Maybe you don’t want it to! When was that?

I was here a lot. Part of 1969 and 1970, again in ’73 and ’74. I lived in Paris in ’74 for a while, about nine months. You know, it was all over the place, wherever the work would take you. And inevitably there would be a woman involved.

You don’t say. You sound like the young Henry Miller!

You’re being generous, that’s a romantic notion right there. It was a fun time because – I don’t know if it’s like that today -- you could get by. There were ways where an artist could be an artist and get by. And because you were an artist, you were invited to all the parties. There was always a free meal around the corner. Back then, there were always plenty of drugs and alcohol. And women. What else does a young man need in his 20s?

Yeah, even accounting for inflation, the money required to live in cities was on a different scale. My brother was also a struggling actor in New York in the mid-‘70s, and he had an apartment on Amsterdam Avenue – around 88th Street, I think – that cost $66. And he could split it with another guy!

Yeah. There were ways that you could stumble by. The big trick was finding somebody that you could tolerate being around for any length of time without killing them. Generally, you’d get up and it was like, “Who could I actually spend an hour or two in the morning with?” Because the days were full of the hustle and the moving around and stuff. And at night it was about trying to get back before the one bed was taken or the bottle of wine that you stashed in the back of the refrigerator was drunk.

I would venture a guess that in those years you were fairly successful in finding people’s beds to sleep in upon occasion.

Upon occasion they would take pity on me and I would find some actual laundered sheets.

Maybe this is an unacceptable gender stereotype, but it’s still true that women are more likely to do laundry, or at least more frequently.

I don’t know about that! I’m not commenting. I’m going to plead the Fifth on that one.

One of the things that strikes me about your work on “Miami Vice,” in retrospect, is that in playing Sonny you’re doing something quite difficult. It’s meant to look like you’re not doing anything. Paul Newman did that beautifully. Brando could do that.

Well, you’re putting me in a rather exalted group of guys there …

No, I know. But the similarity I see is that it may have seemed to the viewer that you weren’t doing anything, that you were just a guy who looked good in the clothes.

You know, the lead writer on that show said to me once, when I first auditioned, “Is this part something that comes natural to you, or are you that good?” I said, “I feel pretty comfortable in the part and, yeah, I’m pretty good.” It’s our job to make it look like it’s effortless. And some of us are better at it than others, I think. Other people struggle.

Sure, yeah. A lot of people can’t do that thing of making it look like they’re not working hard. Al Pacino is one of the greatest actors of our time, or ever. But you never have any doubt that he's working hard. It’s a physical effort that’s visible, he’s got a lot going on. You don’t do that exactly.

Well, that’s a whole discussion about the creative process. I think that it changes when you begin to learn that you’re just the instrument and you don’t really own any of this. When you become aware of that, there’s a lot more that goes on and there’s a lot more that starts to come through. I’ve been experiencing that for the past few years and my characters have been richer as result of that. It’s a lot more fun for me, because when you find something that you love to do and you can do it with joy and enthusiasm, you’re pretty much there.

It definitely looks like you’re having fun at this point. You’re doing interesting work on a variety of different scales. Smaller projects, big projects, movies or TV, those don’t have to be the most important questions.

Yeah, what it’s really about is allowing yourself to be the medium. And not really taking ownership or having attachment to the outcome. So there’s a wonderful freedom that comes with that and I imagine that when other artists become aware of that they must feel similarly to how I feel. There’s a real joy in it.

What was the downside to playing Sonny? I mean, you joked about this earlier, but the upside was obvious. You were famous and well paid. Every woman in the world wanted to sleep with you. But what were the consequences for you personally?

That kind of fame is a prison. There are obvious perks. People are like, “Oh, come on! You’re making lots of money and getting lot of women plus all this other stuff.” And that part’s true. I took a good deal of advantage of – uh, what was availed to me. But at the same token, there’s a receipt for that bill. I’m happy to have survived it. A lot of people don’t.

There’s a particular thing that seems to happen when you’re the star of a TV show, that a lot of people have difficulty transcending. People wonder that right now about Jon Hamm. I guess we could say that George Clooney has done OK!

I think he’s done fine! And I would bet that Jon is going to do very well for himself.

Now, you got another starring role on TV a few years later. And the creation of “Nash Bridges” is kind of an interesting story in itself.

Yeah, Hunter Thompson and I created that concept for what was originally called “Off-Duty Cops.” Hunter and I conceived that together -- he was my neighbor in Aspen and we were very close, very good friends. We conceived it and that eventually became “Nash Bridges.” Hunter was thrilled about that, because he actually got paid a regular salary without having to meet a deadline every week.

Did he actually write any of the show? Because that’s a little hard to imagine.

Yeah, he wrote the original treatment, and then he also wrote an episode down the road. I should say, he wrote a Hunter version of an episode and then I brought that into the grist mill and made it viewable on network television.

Tell me about the legal action you were involved with on that show. You recently got a pretty big payoff – was it from the producers?

No, it wasn’t with the other producers, it was with people that had bought the show for syndication. I own the copyright; I’m a 50 percent owner of the copyright, and they just forgot to pay me. So we had to sort that out.

Was it similar to what James Garner went through to get paid for all those years “The Rockford Files” was in syndication?

It’s dissimilar in that he didn’t own the copyright. He owned a participation in the show. To my knowledge, I’m the only person that’s ever won that lawsuit. You could fill tomes with the stories of people who have been robbed in the film and television business.

Wait -- you’re saying there’s greed and corruption in Hollywood?

Shocking, isn’t it? Almost as shocking as it would be in Washington.

Anyway, doing several seasons on “Nash Bridges” – that wasn’t anywhere near the phenomenon of “Miami Vice,” but it must have made your post-Sonny existence a little bit easier.

And, you know, I had made other films. I made “The Hot Spot” in between, I made “Guilty as Sin” with Sidney Lumet. So I made films that disavowed the notion that I was just a one-trick pony. This most recent thing that I’ve done, “Cold in July,” along with stuff I’ve been doing for that past few years -- “Eastbound & Down,” “Django Unchained,” “Machete” -- those things have pretty much cemented my ability to complete a metamorphosis.

Well, I really like “Cold in July,” and you’re a lot of fun in a movie that ultimately goes to some dark places. Tell me about working with Jim Mickle, the director. I spotted him a few years ago with the zombie movie “Stake Land,” and he clearly had something special.

He’s a gifted filmmaker. After you’ve been doing it as long as I have, you know which questions to ask to find out if someone has film sense or not, and I got the sense right away that he was a gifted filmmaker. And I was right, but I didn’t know how right I was until I saw the completion of “Cold in July.” This is a really good movie.

Did you have anything specific in mind for the character of Jim Bob? I mean, he’s a classic guy in this kind of movie, a private eye with a big cowboy hat and a cherry-red Cadillac convertible. But he’s also very specific. Were you just working off the page?

No. Everyone prepares in different ways, and I do a lot of preparation for characters. Some of the work that I do involves dream work. I ask my subconscious to reveal to me, in dreams, certain aspects of the character. Sometimes it will come out as bizarre allegories that you have to decipher, but it’s never wrong and it never lies. The subconscious has no filter, it has no screen. For instance, on Jim Bob, it would sound crazy if I really told you how it happened, but I wanted an image of what he would look like and I got the image. I called the costumer and said, “I have a sense of what this guy is supposed to look like in term of clothes and I‘m going to buy it.” So I went and bought the hat, the shirt, the belts, the boots, the jeans and stuff like that. I took a picture of myself, sent it to her and she said, “Works for me!” I said, “Well, great; say hello to Jim Bob.”

Do you do the kind of work where you could tell me about that guy’s childhood or whatever?

Well, I could, but that’s more of a … If I had to do an improvisation of the scene, I would put myself in the energy field of that character and see what came out. When you do enough preparation with ritual and research that start to fill your entire senses, subconscious, being and emotion with that character, you can reach for anything. It’s right there. It’s like playing an instrument.

Jesse Eisenberg says that Pacino told him one time, “Kid, just because they say ‘action’ doesn’t mean you have to do anything.” That has stuck with me as a Zen insight into the craft. What do you make of that?

I don’t know. Actors prepare in different ways. I know what Al is saying and it’s probably a good piece of advice for young actors, but for me the word “action” is a trigger. It doesn’t mean you have to do anything, but it means “now that character can be.”

”Cold in July” is now playing in major cities and available on-demand from cable, satellite and online providers.

Shares