There is no mystery why libertarians love the Internet and all the freedom-enhancing applications, from open source software to Bitcoin, that thrive in its nurturing embrace. The Internet routes around censorship. It enables peer-to-peer connections that scoff at arbitrary geographical boundaries. It provides infinite access to do-it-yourself information. It fuels dreams of liberation from totalitarian oppression. Give everyone a smartphone, and dictators will fall! (Hell, you can even download the code that will let you 3-D print a gun.)

Libertarian nirvana: It's never more than a mouse-click away.

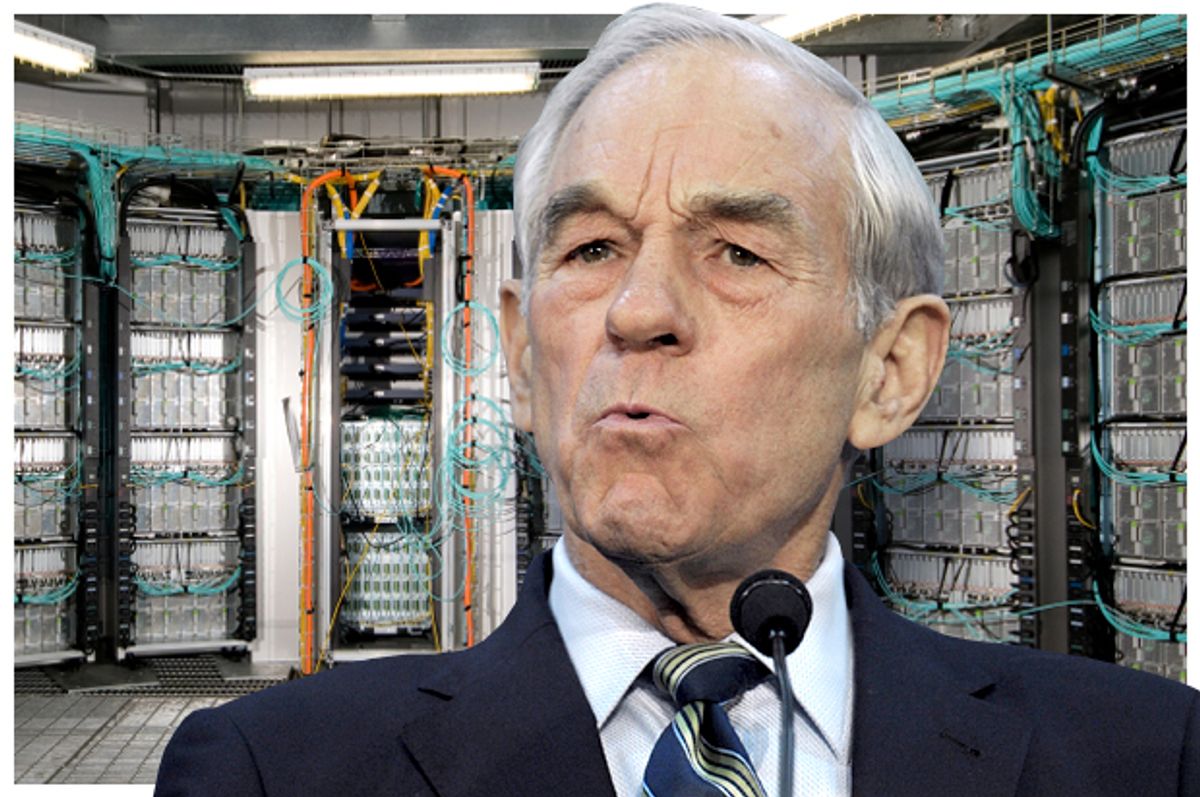

So, no mystery, sure. But there is a paradox. The same digital infrastructure that was supposed to enable freedom turns out to be remarkably effective at control as well. Privacy is an illusion, surveillance is everywhere, and increasingly, black-box big-data-devouring algorithms guide and shape our behavior and consumption. The instrument of our liberation turns out to be doing double-duty as the facilitator of a Panopticon. 3-D printer or no, you better believe somebody is watching you download your guns.

Facebook delivered a fresh reminder of this unfortunate evolution earlier this week. On Thursday, it announced, with much fanfare and plenty of admiring media coverage, that it was going to allow users to opt out of certain kinds of targeted ads. Stripped of any context, this would normally be considered a good thing. (Come to think of it, are there any two words, excluding "Ayn Rand," that capture the essence of libertarianism better than "opt out"?)

Of course, the announcement about opting out was just a bait-and-switch designed to distract people from the fact that Facebook was actually vastly increasing the omniscience of its ongoing ad-targeting program. Even as it dangled the opt-out olive branch, Facebook also revealed that it would now start incorporating your entire browsing history, as well as information gathered by your smartphone apps, into its ad targeting database. (Previously, ads served by Facebook limited themselves to targeting users based on their activity on Facebook. Now, everything goes!)

The move was classic Facebook: A design change that -- as Jeff Chester, executive director of the Center for Digital Democracy, told the Washington Post -- constitutes "a dramatic expansion of its spying on users."

Of course, even while Facebook is spying on us, we certainly could be using Facebook to organize against dictators, or to follow 3-D gun maestro Cody Wilson, or to topple annoyingly un-libertarian congressional House majority leaders.

It's confusing, this situation we're in, where the digital tools of liberation are simultaneously tools of manipulation. It would be foolish to say that there is no utility to our digital infrastructure. But we need to at least ask ourselves the question -- is it possible that in some important ways, we are less free now than before the Internet entered our lives? Because it's not just Facebook who is spying on us; it's everyone.

* * *

A week or so ago, I received a tweet from someone who had apparently read a story in which I was critical of the "sharing" economy:

[embedtweet id="476020876614586368"]

I'll be honest -- I'm not exactly sure what "gun-yielding regulator thugs" are. (Maybe he meant gun-wielding?) But I was intrigued by the combination of the right to constitutionally guaranteed "free association" with the right of companies like Airbnb and Uber to operate free of regulatory oversight. The "sharing" economy is often marketed as some kind of hippy-dippy post-capitalist paradise -- full of sympathy, and trust abounding -- but it is also apparent that the popularity of these services taps into a deep reservoir of libertarian yearning. In the libertopia, we'll dispense with government and even most corporations. All we'll need will be convenient platforms that enable to us to contract with each other for every essential service!

But what's missing here is the realization that those ever-so-convenient platforms are actually far more intrusive and potentially oppressive than the incumbent regimes that they are displacing. Operating on a global scale, companies like Airbnb and Uber are amassing vast databases of information about what we do and where we go. They are even figuring out the kind of people that we are, through our social media profiles and the ratings and reputation systems that they deploy to enforce good behavior. They have our credit card numbers and real names and addresses. They're inside our phones. The cab driver you paid with cash last year was an entirely anonymous transactor. Not so for the ride on Lyft or Uber. The sharing economy, it turns out, is an integral part of the surveillance economy. In our race to let Silicon Valley mediate every consumer experience, we are voluntarily imprisoning ourselves in the Panopticon.

The more data we generate, the more we open ourselves up to manipulation based on how that data is investigated and acted upon by algorithmic rules. Earlier this month, Slate published a fascinating article, titled "Data-Driven Discrimination: How algorithms can perpetuate poverty and inequality."

It reads:

Unlike the mustache-twiddling racists of yore, conspiring to segregate and exploit particular groups, redlining in the Information Age can happen at the hand of well-meaning coders crafting exceedingly complex algorithms. One reason is because algorithms learn from one another and iterate into new forms, making them inscrutable to even the coders responsible for creating them, it’s harder for concerned parties to find the smoking gun of wrongdoing.

A potential example of such information redlining:

A transportation agency may pledge to open public transit data to inspire the creation of applications like “Next Bus,” which simplify how we plan trips and save time. But poorer localities often lack the resources to produce or share transit data, meaning some neighborhoods become dead zones—places your smartphone won’t tell you to travel to or through.

And that's a well-meaning example of how an algorithm can go awry! What happens when algorithms are designed purposely to discriminate? The most troubling aspect of our new information infrastructure is that the opportunities to manipulate us via our data are greatly expanded in an age of digital intermediation. The recommendations we get from Netflix or Amazon, the ads we see on Facebook, the search results we generate on Google -- they're all connected and influenced by hard data on what we read and buy and watch and seek. Is this freedom? Or is it a more insidious set of constraints than we could ever possibly have imagined the first time we logged in and started exploring the online universe.

Shares