At this point, years removed from when the Great Recession that began in 2007 technically ended, most everybody appreciates how the financial armageddon that gripped the world in late-2008 and early-2009 brought on profound economic changes that, in one way or another, we're all still living with today. At least in the United States and the United Kingdom today, we now live with a new normal of high unemployment, low growth, fewer savings and more uncertainty. (For proof of this last point, see the common "don't panic...yet" response to Wednesday's revelation that Q1 growth in the U.S. was far weaker than previously understood.)

Less appreciated, however, is the way in which the Great Recession has taken many of the worst social effects of inequality and capitalist dysfunction and intensified them, turning lives that were already precarious — and futures that were already uncertain — and transforming them into slow-rolling disasters. And while the stock market can always bounce back and corporate profits can always recover, for millions of people who lost opportunities to build financial stability for themselves from which to help create a healthy, broader community, the social ills born from the Great Recession will last a lifetime.

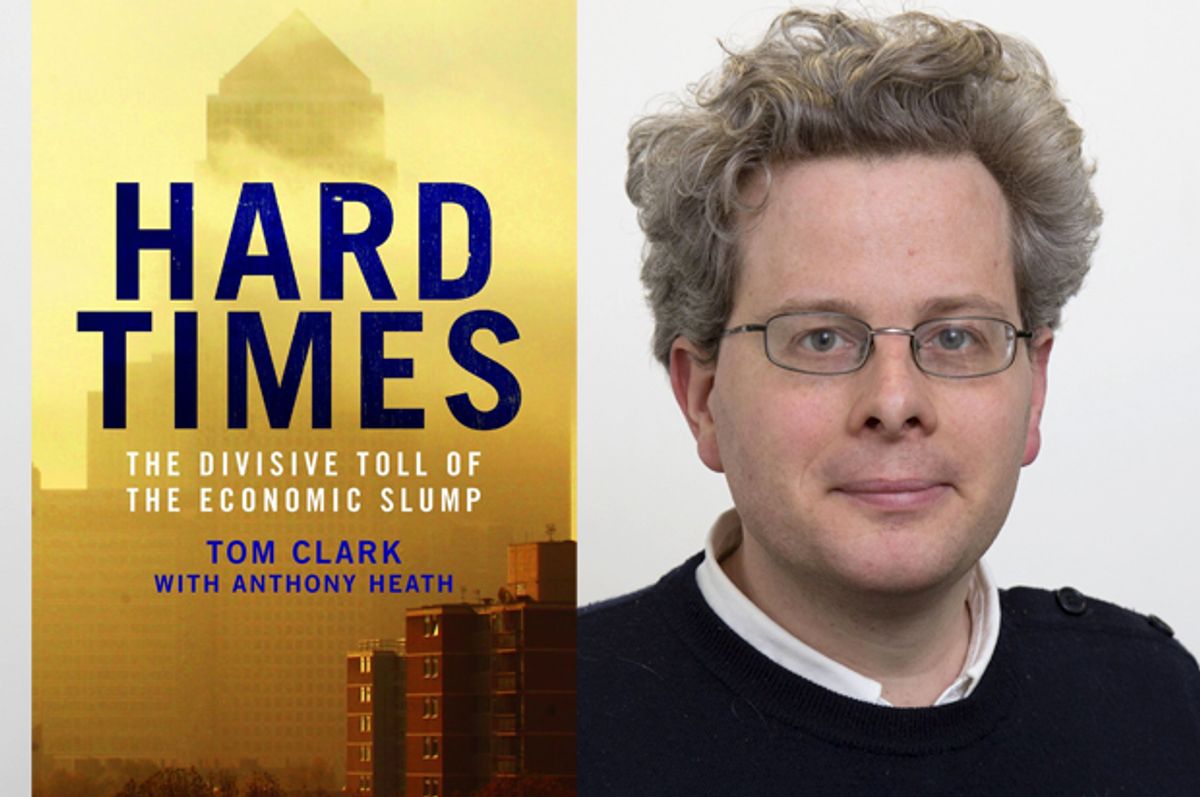

Earlier this week, Salon called up Tom Clark, a journalist for the Guardian, to discuss these societal harms and "Hard Times: The Divisive Toll of the Economic Slump," the new book he co-wrote with University of Manchester sociologist Anthony Heath about the subject. We also touched on the economics of inequality and how the political right in the U.S. and the U.K. has tried to divert attention away from their destructive economic policies and shift the blame instead onto the so-called 47 percent, the very people most harmed by the Great Recession. Our conversation is below, and has been edited for clarity and length.

What was it that made you want to write this book?

Some years ago now, I studied economic history at university and I could see what was unfolding from 2008 onwards was something that, in some ways but not in others, was eerily reminiscent of the Great Depression and the great social disruption that we remember in popular memory from that time, and I just thought that to be alive in these times, to be living through these times, it would be fascinating to try and make sense of it in the way [that], on a fiction front in America, we remember "The Grapes of Wrath." (Here in the U.K., we remember a book called "The Road to Wigan Pier" by George Orwell.) ... A little while after the recession, I thought, "It’s gonna take time for the impressions and the consequences of this huge financial event that we keep hearing about in the media to become clear.” And having read about what happened last time around [during the Great Depression], it could also be [worthwhile], trying to make sense of what happened this time around in real time.

All right, well, here's a big question, but: What is happening "this time around"?

Goodness, yes, it’s probably as well to try and narrow that down. One thing I deliberately try to do — and I think this comes with, you know, having looked at the Great Depression and having taken a long view — is note that societies have got a bit poorer, ut they’re very rich societies by the international standard or by any historical standard ... Really, they should, one would have thought — certainly people in the 1930s looking forward to this time — would have expected that this [kind of economic damage] is something that comes and goes by the time societies have grown this rich and this technologically advanced as well. That by this time, this is something we really should’ve been able to take on the chin, should’ve been able to manage without huge disruption ...

We should’ve been able to do that, but, in practice — and I think this goes down to America and Britain being such unequal societies — we weren’t able to do so. We find that there had been very grave consequences in terms of social engagement — particularly in Britain. We find that there’s great consequences in terms of mental well-being, which are at least as marked, perhaps more marked, in the United States than they seem to be in Britain. And we find that there are consequences too —certainly more suggestively, but there’s still a lot to convince me — in terms of family relationships and how people get on with their nearest and dearest. All of these things that we like to think that money shouldn’t be able to buy — friends, family, community — all of these things have been tainted by the social fallout of Great Recession. Not, I think, because it’s a rich society that’s got a bit poorer, but because it’s a society that’s left so many people with so little for so long during the good times, that there’s a large chunk of society down at the bottom-end that really can’t afford to get a bit poorer, even if the average person could.

That gets to what I think is one of the most distinctive features of the so-called recovery period, the perception gap between those who are on the winners' side of the economic spectrum and those who are not. In terms of estimations of how bad things are out there, it can feel at times as if big chunks of people in the U.S. and U.K. are living in separate worlds.

I think during a lot of [the 30 or so years preceding the Great Recession] there was — you’ve heard the phrase "trickle-down economics" — there was this belief that ... in the end, the effects of [entrepreneurial wealth] would filter through to everybody else. In practice, I think a lot was hidden because the people who weren’t sharing in the full growth and continuing march of technology and everything — there were a burgeoning range of options for credit before 2007 and more people were buying homes, and ... maybe by borrowing more money on the strength of those homes. There was a sense that even if it seemed a bit unfair, there were still opportunities as people could get on the property ladder or could maybe invest for the first time in a few stocks and shares. There was a promise of a more widely shared prosperity, even as incomes got more unequal.

I think really what happened in 2008 is that the music stopped and people kind of realized that the inequality that had been building up wasn’t something that was going to be solved by incomes trickling down or by magic money coming out of houses or by people talking themselves into believing their assets were worth twice as much as they previously believed. Actually, people’s sense of what they were worth, how their future was going, was probably better guided by rather miserable pay packets than it was by blown-up hopes that they’d get rich on the profits on the back of the property market or something. In other words, I think the scales fell from our eyes and we saw this big inequality that had been slowly, slowly building up was a permanent thing and something to worry about because there was no way out of it while incomes remained so unequal. There was to be no opportunity for the mass of people while their incomes remained so depressed. So we had a moment of reckoning in 2008 and 2009 for an effect of inequality that had built up over a whole generation.

It’s not so much that the Great Recession made inequality worse; it didn’t, actually. It simply revealed the full consequences. So the phrase I use in the book I think is, rather than deepening the inequality — it was already very deep — what the Great Recession did was widen it into a chasm that does affect these things like mental health and community bonds and family relationships, so that large bits of society, large parts of each of these countries that have been left behind over a long period, are now very frail in social terms. They lose hope when they realize there’s no magic way out of the fact that pay packets have been stagnant for years and years. And when hope goes, then you see a penalty in all these terms—family, community, and friendship.

So would it be fair to describe the relationship between the Great Recession and economic inequality as sort of like that between, say, a bruise and cancer? Meaning: In the same way people sometimes end up going to the doctor because they have a bruise that won't heal only to find out that the reason it won't heal is because they have leukemia, the societies of the U.S. and the U.K. experienced the Great Recession as an obvious manifestation of the deeper, underlying sickness, which is economic inequality?

I think that works, absolutely ... I think absolutely there was a frailty there before — a frailty that was maybe covered up by this feeling of rather naïve optimism that was generated by a sense that more people were buying houses, and houses were going to be worth more, essentially; and when that came to a standstill, we saw that there was indeed a really frightening frailty [to our economies]. I like your metaphor a lot. We talk about scars in the book, scars left by a recession. But, in a way, I think yours is a neat way to describe it. There was an underlying condition. This thing isn’t healing in the way that it should be. Another way of putting it, perhaps, is that we had 30 years where things were rotting away under the surface and then when the tide went out there was some fairly ugly material left on the beach.

Let's talk about that ugly material, then. What are some of the social maladies you've found concentrated on the lower end of the wealth scale in the recovery era?

This was a large cross-sectional survey, that we started across France, Germany, the US and the UK [and] over the last several years, we asked people two questions: 1. Over the last several years ... how affected have you been by the economic problems in your country? And then we asked them, 2. Are you now less involved than you were with community groups or social clubs? And what we find in France and Germany is that there is not much of a difference between the people who got knocked by the recession and the people who weren’t knocked by the recession ... But in both Britain and America, there’s a really strong gradient so that, roughly speaking, people who said they were affected by the recession are now twice as likely to say that they’re less involved in community groups than they used to be as people who say they by and large got through the recession unscathed. So that’s quite a striking difference between continental economies and Anglo-Saxon economies for what sociologists would call "social capital" — how involved people are in community groups and clubs ...

We came to the same point again by looking at the anxiety gap. Now, if you think of all the things that can make people feel anxious — whether romances gone wrong, to turbulent teenage children, etc. — there are so many things that have nothing to do with the economy that would have a big effect on people’s anxiety. But we found a really, extraordinarily close connection here. In the U.K., for example, people who said they were not at all affected by the recession, only 20 percent of them said that they now feel more anxious than they used to a few years ago ... When we looked at people who were affected by the recession a great deal, that rose to something like 80 percent ... A really, really close connection between people’s exposure to the recession and how much anxiety they feel ... But when we look at France, there’s still an effect, as you’d expect — there’s a bit more anxiety among people who have suffered more in the recession — but it’s an altogether smaller gap. I think it’s a gap, in percentage point terms, of just 13 points in France, whereas ... in the U.K., it’s 30 percentage points, and in the United States, it’s a 34 percentage point gap between the recession-hit group, the broadly defined recession hit group, and the broadly defined recession-proof group.

So we're living in separate worlds not only in the sense of economics but also in a more psychological (or even spiritual) sense, too.

I think that’s exactly right ... When we’re looking at these social effects, more than in the economic effects, we see misery and pain as concentrated on the minority on the bottom of the heap. I think if you’re a family that’s got middling pay — and your pay might have been fairly stagnant over a number of years, but you’re a family that’s stayed together, and both people have stayed in work, and you’re educated and so you still have some options about what job you might do next — then it hasn’t poured over into poisoning these non-financial aspects of life in the same way, whereas it’s people who are really down in the bottom of the heap — school drop-outs, ethnic minorities, people who live in dead end towns, all the groups that we’re used to thinking of having tough times over many years — their proportional economic losses might not be bigger than those in the middle, but it looks like the social consequences of the long years of neglect are really catching up with them now.

How much do these findings make you worry about the capitalist, liberal democratic model of government? Do you worry that it's failed or unsustainable if it not only perpetuates economic inequality and suffering but psychological and social dysfunction, too?

It’s a good question, and I’m not going to pretend it’s a question we’ve settled in this book which is largely about society. If we look at the Thomas Piketty book, "Capital in the Twenty-First Century," he talks a lot about the fundamental dynamics he sees of unregulated capitalism that will point towards greater inequality; and some people have said, "Yes, we need big structural change." Piketty himself is a bit more cautious.

I would be a bit more cautious for this reason, which is, I’ve been talking here about some of the differences between the continental European societies and Britain and the United States, which suggests that within the range of liberal democratic capitalist societies it is possible to do quite a lot [better]. And even from a British perspective, looking at America — I mean, I was staggered to find out that, for example, depending on how you adjust for inflation, it looks like the minimum wage in the U.S. today is as low as it was in the middle of the Eisenhower era, during a 50 or 60 year spell when American GDP has sort of gone up two- or three-fold, 200 or 300 percent. If you were a minimum wage worker, what you were taking home hasn’t gone up at all. You’ve been denied any advantages from progress in technology during all of that time. That seems to me to be a choice about how you want to run the economy rather than something that’s absolutely inevitable about any form of capitalism because, in Germany — whether it comes in the form of consultation with unions and other forms of worker groups or straightforward regulation of things like minimum wages — they’ve ensured that people in lowly jobs, over the very long term ... are getting a much fairer share of the overall technical and economic progress, they’re getting a more equal share of the growth in their societies. So I think that what we’re seeing really is the bankruptcy of ... not of capitalism as a whole, but the way that we’ve run capitalism [in the U.S. and U.K.], some would say since the 1970s, since Reagan and Thatcher, some might say more particularly since the Berlin Wall came down. We started to think free-for-all capitalism was the only type of capitalism. Rather than a problem of any form of market, I think it’s a problem with the unregulated, unmediated form of market economy that we’re seeing.

Separate from your own estimation of the system's virtues and sustainability, though, do you ever worry that the generation growing up in these economic conditions might end up drifting more toward illiberal, authoritarian ideologies as a response to what they think is a discredit status quo? As I'm sure you're well aware, one of the things that happened as a result of the Great Depression — obviously in Germany, Italy and other European nations but also to some degree in the United States and United Kingdom, too — is that it became kind of en vogue for people to argue that the Great Depression and its aftermath proved capitalist liberal democracy was outdated or simply not up to the tasks confronting it.

I’m worried that people are angry, and that poisons politics. I’m worried that in both the U.S. and the UK, there’s this bizarre thing now where the rich, the elite, are trying to turn the middle against the poor. So you’ll remember Mitt Romney talking about the 48 percent who never vote and expect their welfare checks — do you remember this?

Oh, sure. He was referring to the 47 percent of people who, because of the earned income tax credit and various anti-poverty measures, don’t pay a federal income tax.

Yes, that’s right, 47 percent. He was also implicitly saying, “These people are so [lost] and disconnected that they won’t vote so we don’t need to worry about them." Here in the U.K., we’ve had a Chancellor of the Exchequer [George Osborne] — who’s from a titled family and one day will become what’s called a Baronet — [who] makes speeches in which he talks about people who are unemployed and spend their days in bed sleeping off a life in benefits ... someone who’s out on a big night of drinking, whereas in fact he’s talking about someone who’s stayed in because they've got no money and are probably worrying about turning the heat on. So I really do think you’ve got some divisive policies going on, and you’ve got quite a lot of hate-mongering going on, in terms of the people who have been the worst victims of this recession are kind of being blamed for the fact that there are big bills, big economic bills, on the way out of the recession. Because, yes, a lot of money has been paid on unemployment compensation and retraining programs and so on but, of course, it tends to be less money that what we’ve spent on bailing out the banks. It seems to me that there’s a very ugly blame game going on that’s directed — is orchestrated — by people who are doing very nicely at the top to turn the sort of great middle class that itself is feeling squeezed against people at the bottom. Mitt Romney didn’t get elected; the government here is not particularly popular; but there is some evidence ... that they have some success in turning the anger and resentment of, if you like, the squeezed middle, downwards rather than upwards. So I’m worried about that.

Shares