On both sides of the Atlantic, the English-speaking giants, the United States and United Kingdom, are moving to extend their data empire over the rest of the world.

While both these power grabs may be a delayed response to Edward Snowden's disclosures, neither explicitly deals with it. And both power grabs extend beyond intelligence collection to common crime fighting.

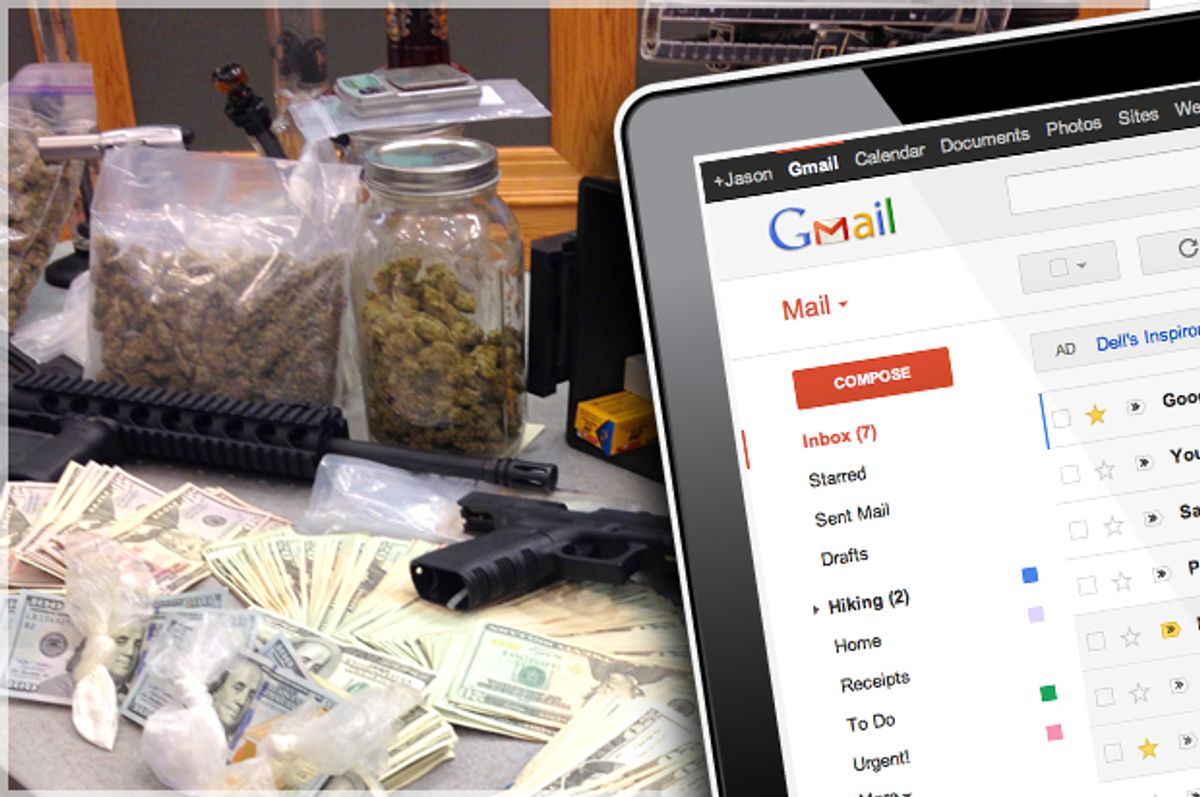

The U.S. data grab started back in December, when the Department of Justice applied for a warrant covering an email account Microsoft held in Ireland as part of a drug-trafficking investigation. Microsoft complied with regards to the information it stored in the U.S. (which consisted of subscriber information and address books), but challenged the order for the content of the emails. After Magistrate Judge James Francis sided with the government -- arguing, in part, that Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties, under which one country asks another for help on a legal investigation, were too burdensome -- Microsoft appealed, arguing the government had conscripted it to conduct an extraterritorial search and seizure on its behalf.

As part of that, Microsoft Vice President Rajesh Jha described how, since Snowden's disclosures, "Microsoft partners and enterprise customers around the world and across all sectors have raised concerns about the United States Government's access to customer data stored by Microsoft." Jha explained these concerns went beyond NSA's practices. "The notion of United States government access to such data -- particularly without notice to the customer -- is extremely troubling to our partners and enterprise customers located outside of the United States." Some of those customers even raised Magistrate Francis' decision specifically.

The other American cloud computing companies piled on with amicus curiae briefs supporting Microsoft's position: Verizon, AT&T, Apple, Cisco, Infor, as well as the NGO Electronic Frontier Foundation.

The government's response, however, argued U.S. legal process is all that is required. DOJ's brief scoffed at Microsoft for raising the real business concerns that such big-footing would have on the U.S. industry. "The fact remains that there exists probable cause to believe that evidence of a violation of U.S. criminal law, affecting U.S. residents and implicating U.S. interests, is present in records under Microsoft’s control," the government laid out. It then suggested U.S. protection for Microsoft's intellectual property is the tradeoff Microsoft makes for complying with legal process. "Microsoft is a U.S.-based company, enjoying all the rights and privileges of doing business in this country, including in particular the protection of U.S. intellectual property laws." It ends with the kind of scolding usually reserved for children. "Microsoft should not be heard to complain that doing so might harm its bottom line. "

However the legal fight ends up, this is largely legal theater in which a bunch of providers -- including some of the ones (like AT&T and Microsoft) that have been most amenable to government intelligence collection requests -- make a show of resisting the iron fist of U.S. demands.

Nevertheless, it makes clear that the U.S. feels free to demand data from U.S. companies no matter where that data is stored. So while Microsoft's challenge largely serves to make its legal obligations visible to the rest of the world, the legal case may have real consequences, both legally and economically.

Meanwhile, on Tuesday the United Kingdom rushed an "emergency" Data Retention and Investigatory Powers bill (DRIP) through Parliament. There was, in fact, no emergency; at least, the British government had made no response to an April European Court of Justice decision that its existing data retention law did not meet EU protections for privacy until British privacy groups moved to challenge their practice. But then on July 10, the British government introduced the bill and started wailing about an emergency posed by organized criminals and terrorists, leading Parliament to approve an accelerated consideration. Parliament had to approve DRIP immediately, the government said, to ensure the government could continue to access all metadata if needed.

The British government claims DRIP only authorizes existing authorities. But opponents argue DRIP includes a broad new definition of Web services that may extend beyond Web-based email services like gmail.

More important, DRIP would extend British authority to include non-British companies. The government can require companies outside of the U.K. to intercept and hand over data. Fifteen Internet law experts argued in a letter that the U.K. power grab could introduce something entirely new. "DRIP attempts to extend the territorial reach of the British interception powers, expanding the U.K.’s ability to mandate the interception of communications content across the globe," the experts argued. "It introduces powers that are not only completely novel in the United Kingdom, they are some of the first of their kind globally."

It's possible the U.K. is seeking such an expansion in the wake of actions some companies -- notably, U.S. telecom Verizon, which split from its British partner Vodaphone earlier this year -- have taken that may put them beyond the reach of the U.K.'s intelligence wiretapping agency, GCHQ. It may be that the U.K., like the U.S., just doesn't feel the need to respect international boundaries anymore.

Though it's not as if either country was respecting boundaries in their intelligence collection; Snowden's disclosures reveal the two countries, which partner closely on SIGINT, collect data from intercept points all over the globe.

It's just now that both countries are publicly claiming they have the legal authority to do so, and do so for criminal purposes, not just intelligence ones.

DRIP will surely become law in the U.K., though it may be challenged at the EU again. It's uncertain whether Microsoft will win its challenge in New York.

But the real question is how the rest of the world will respond to the claim -- from both the United Kingdom and the United States -- that they can legally grab content both at home and abroad.

Shares