Like presidential elections or leap days in February, America’s love affair with soccer seems to happen once every four years. We feed heavy on the game for a summer month and then go into wintry, quadrennial hibernation: TV ratings spike. Newspapers and magazines fill with pre- and post-game analysis. Bars and cafes ring with spectators gasping and clapping and falling over one another to catch a glimpse of the action.

Our short-lived World Cup mania invites a basic incredulity: how is it that Americans everywhere, normally deaf, dumb and blind to the charms of the “beautiful game,” have suddenly taken so keen an interest in it? Will the country’s focus quickly shift from the soccer pitch to one of its other athletic divertissements, now that the World Cup has ended, and the smoke has cleared from Team U.S.A.? Or are we finally becoming a nation of full-time soccer fanatics?

As anyone who followed the World Cup punditry over the past month can attest, such questions tended to produce certain patterns of reaction: at one end of the spectrum were the soccer optimists, who viewed our embrace of the World Cup not as a passing flirtation, but as part of a sustained, ever-solidifying national romance with the game. Buttressed by data showing that soccer is growing in popularity among today’s youth and that — despite negligible television ratings — attendance at MLS games (America’s Professional Soccer League) is on the rise, they concluded that the sport’s stateside future has never looked brighter.

Then there were the agnostics who participated fully in our soccer jubilee, but questioned whether it would have the traction others hoped for and expected. These skeptics pointed to the obvious: for a majority of Americans, soccer spectatorship still begins and ends with the World Cup — or, at least, the U.S. national team’s entry into and customarily early exit from the tournament. And they doubted whether the game could ever find equal footing in our already sports-saturated country. (What with all the football and basketball and baseball teams we follow, and the fantasy teams when we’re not following those). Habits, they seemed to remind us, die hard. National sporting habits harder than most.

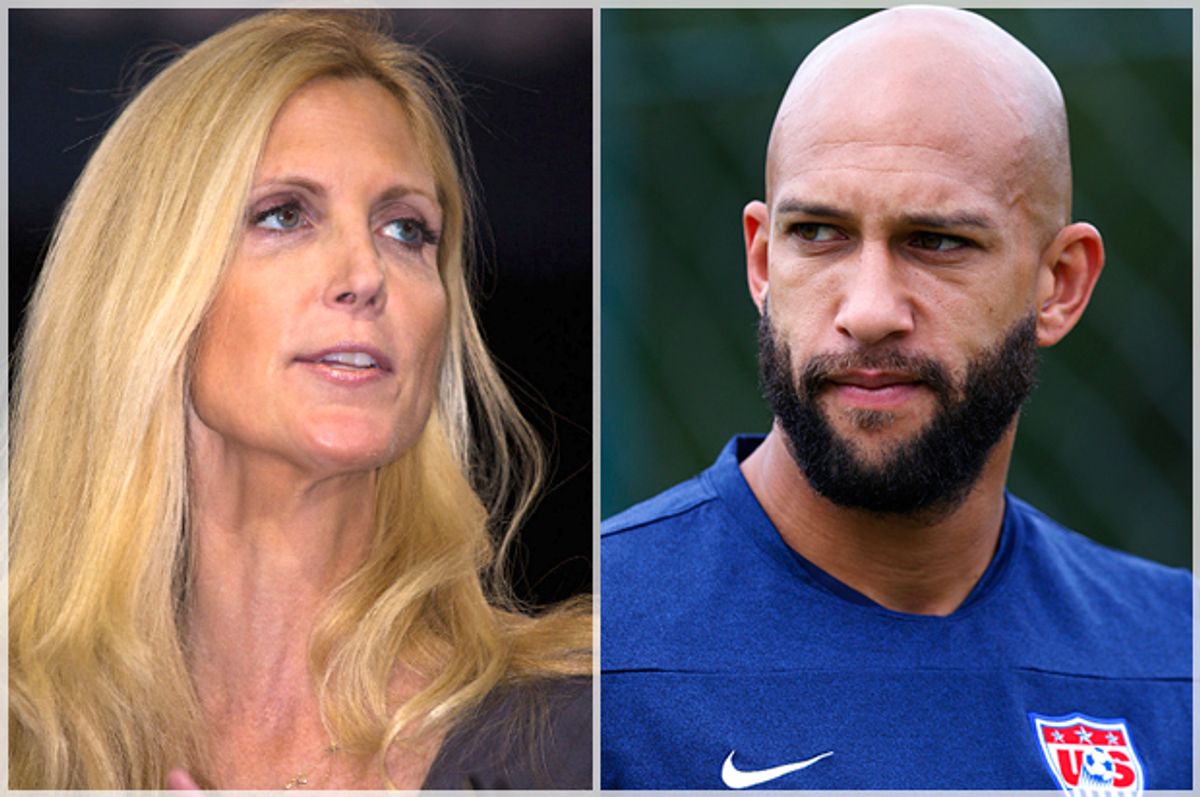

Finally, at the opposite end of the spectrum, were the game’s recalcitrant opponents, who tried to undercut our enthusiasms by insisting that soccer and America are mutually exclusive. Sounding the battle cry, Ann Coulter, the conservative polemicist, wrote a widely circulated piece denouncing America’s “soccer fetish.” Amidst reports of record-breaking ratings for the U.S.-Portugal group match, Coulter’s patience was apparently stretched beyond the breaking point: “Enough is enough. Any growing interest in soccer can only be a sign of the nation's moral decay.” Among other sins, she warned us that soccer subverts and downplays “individual achievement” (translation: it’s socialism in cleats) and what she admiringly described as “threat of personal disgrace” (i.e., manliness). She called the game boring (too little violence; not enough scoring), and so maddeningly foreign that it reminded her of the “metric system.” Quelle horreur! According to Coulter, real Americans everywhere (the sort “whose great-grandfather was born here”) are being brainwashed and victimized by a bunch of sissy, left-wing soccer evangelists. But the true culprit behind all this recent soccerphilia? “Teddy Kennedy's 1965 immigration law.”

*

As a display of special pleading and pandering illogic, Coulter’s broadside can hardly be improved upon. Yet there is one aspect of her opposition that may still have its explanatory uses: Coulter views the country’s burgeoning interest in soccer in relation to its ethical life — or, in her more pointed language, its “moral decay.” But her alarmism aside, the question of what our response to the World Cup says about the culture at large — not just what it portends for the future of soccer, which most commentators focused on — remains important and, if anything, overlooked.

What if this summer’s soccer frenzy had less to do with soccer per se than with the distinct set of values the World Cup gave rise to? Or, emphasized differently, what if the real source of our World Cup obsession was not some new, mass appreciation of the game, but the relative impoverishment of today’s celebrity culture, in which so much of experience is mediated vicariously through our electronic gadgets? We live in an age of social media self-inflation and widespread financial deregulation; a disconnected age that prizes individual autonomy over traditional social ties. But if the record-breaking ratings for the Team U.S.A. games were any indication, many of us still yearn to identify with a group. Suddenly, an event like the World Cup comes along that feels exciting and alive and that reminds people just how meaningful it can be to fully commit to something as part of a collective.

This, in part, is what draws spectators to sports to begin with: the fervid sense of purpose and community that consoles us against — or merely distracts us from — the disenchantments of modern corporate life. Rather than building sustainable franchises fans can identify with, however, owners today compete to outbid one another on a cluster of celebrity superstars. And players, understandably, rarely remain on any one team for more than a few seasons before seeking out more lucrative opportunities. By contrast, the U.S. national squad was conspicuously lacking in individual aggrandizement. (How many fans could have named more than a single team member before the tournament began?) Indeed, the team’s unglamorous, down-home quality was precisely a source of its appeal. It pointed forward (and back) to a less mercenary culture of sports, in which rooting for a team is not just about winning, but a matter of collective identity — a birthright you can take pride in.

Such sentiments are increasingly rare these days, and, in this respect, the World Cup remained a vital outlet: it allowed us to identify with something larger than ourselves. More than even the Olympics, with its diffuse, around-the-clock, multi-event extravaganza, the tournament focused and concentrated our dormant nationalist energies: the whole country following the same game, at the same time, together. To watch the U.S. national team at a neighborhood bar or on an outdoor screen, along with a random assortment of Americans, and to burst into stranger-hugging frenzy (as happened when Jermaine Jones “equalized” against Portugal, or when Julian Green scored a late, rallying goal against Belgium), was to experience your identity momentarily yet blissfully subsumed within a larger collective. Never mind soccer. Think of it as the re-enchantment of contemporary life.

The impulses behind this summer’s World Cup in the U.S. were, of course, many and various, and not always admirable. For certain fans, the tournament may have simply been another media spectacle — the latest turn in our cycle of national distraction — or, otherwise, a mere pretext for chauvinistic chest-thumping. Yet, it seems equally the case that many Americans experienced an awakening of genuine patriotic pride while watching Team U.S.A.. That this occurred during an international tournament, through a sport that has often been called un-American, is all the more telling. It indicates that we can love our country without succumbing to narrow-minded exceptionalism, but on the contrary, by opening ourselves up to foreign influence. And it reveals a shared desire to extend beyond the boundaries of autonomous, anatomized contemporary life. Viewed from this perspective, the country’s “soccer fetish” represented not its “moral decay,” but a small kind of moral victory, in which individuals joined together to achieve a greater sense of belonging and fellow feeling. And that, at least, is something that everyone — soccer optimists, agnostics, and opponents alike — should be able to celebrate.

Shares