Anonymous asks: When people compliment your work, do you feel awkward? Do you believe them or do you suspect they are only being polite? Have you figured out how to graciously accept such compliments?

So here’s a story. Last week I went to a party. It was a big party, and it was in Brooklyn, and it was full of writers and agents and men with tie bars and a few women with retro-peacockish things clipped in their hair. This was an annual party, and during the two years or so after I’d sold my book and was panicking while I rewrote it from scratch, I had been invited to this party and had politely declined, in part because I just couldn’t face a room of people, so many of whom I admired, asking me when my book was coming out. That had become, I guess, a bit of a trigger for me, and it was easier just to avoid it than it was to try to explain why I hadn’t turned in the edits or really what the hell was going on with me. But this year I went because my book was done and out and had been received (if somewhat quietly) and anyway of course this party wasn’t really about me.

When I arrived they handed me a signature cocktail, a plastic cup that I suspect was mostly full of gin because by the time I had finished it I couldn’t feel my cheeks. This, I gather, was the case for almost everyone else because soon the place was roaring and a band was playing some sort of swing-sounding music and I was gabbing freely with people I’d never met before. In other words I was having a great time—it was a great party—and I was wondering why in the world I had ever avoided it. Earlier that day I had received a rejection for something I had applied for, one that felt rather personal, but the booze and the chatter had all but numbed the sting of it. I was hugging acquaintances and was smiling at strangers like we were old friends and repeating the title of my book to everyone I was introduced to, who leaned in to listen because I guess they had never heard of it and wanted to know; one guy even tapped it into his iPhone, which made me feel nice.

Finally there was a woman next to me, a somewhat familiar woman, though I couldn’t remember from where, who was telling me that she had read my book. “I actually liked it,” she was saying. I had no idea who she was, but I could guess from her enunciation she had been given the same cocktail I had. “Thank you,” I said. “It reminded me of Cheever. But not in a derivative way.” “Thank you,” I said. “I mean I didn’t end up finishing it, but you have to understand how many books I have to read.” “Of course,” I said. She squinted somewhere far off, as if remembering the pages she had actually read, and confirmed her assessment with a nod. “But yeah, I did like it.”

I didn’t last too long at the party after that.

I wish I could explain why it was a compliment—one that, despite her tipsy admission of not finishing the book, I do believe was sincere—that punctured me. Or why it was that as soon as she mentioned my book, trying to be nice, no doubt, I could only hear her reservation, could only assume that under the tepid word “like” there was an unspoken iceberg of criticism that was in fact the truth. Or why I seemed to care at all.

There is something I’ve noticed among almost every writer I know, including those who publish big, beloved books right out of the gate, which is that there can be a residual shame that comes from publishing anything—or indeed from showing anybody something you’ve written. This is something that gets addressed in workshop settings and maybe among friends in a writers’ group, where presumably you’re discussing drafts and how to make them better. But I don’t think it gets talked about much (at least not publicly) among writers who finally have a book come out. This, I assume, is because having anything published is an honor, so it’s probably wise not to complain. Your job is to be an ambassador for your book, to stand by it and introduce it to the world—shining its shoes and combing its hair and talking about the little guy’s strengths. But underneath that of course there is something else going on, a feeling of exposure that is at once exhilarating and also can be wholly debilitating.

I don’t think it’s necessarily the fear of criticism or failure. That’s somehow different. And I say that because criticism is a stance, it’s another way of showing your hand. This shame is something that manifests mostly in the compliments, in the half-truths and coded language of chitchat, in the casual emails from a distant relative’s book group. I’ve spoken with one writer, whose book was very well received, who said that at its worst she had the urge to take all of her books back, just pull them from the whole world, and pretend the whole thing had never happened. As extreme as that sounds, I have totally had that urge. Of course when it comes down to it you don’t really want that, but at its worst this shame can make you want to curl up in a ball and disappear.

Exposure, of course, is one of the things we’re after when we write anything. It’s why we do it—to communicate openly, to express something honest or otherwise unsayable, something that cuts through the social language of platitude and concealment, the empty exclamation points of daily email. You want to show your hand, and if you’re not risking that vulnerability on some level, if you’re just performing, or flexing the big muscle of your brain, then chances are it won’t be all that interesting. At least not to me. Writing is a project of revealing—of revelation—and the deeper it cuts generally the more engaging it is.

But as a writer, this can put you in a kind of emotional Chinese finger trap. You intentionally expose and then every polite reaction can feel like a disguised slight. There are television self-helpers and a certain kind of macho author who would say that your self-esteem should have nothing to do with other people’s opinions, and while that’s a nice idea, I say that’s probably crap. A fantasy. Because nothing about writing is one-sided, a person in a vacuum banging out books to an adoring public, a macho guy with a beard and a bolo tie invulnerable to other people. A book is nothing, a pile of paper, until it’s engaged by the mind and imagination of a reader. That’s where it comes alive. That’s where it exists. And chances are you got into this writing racket precisely because you’re sensitive to these things, because, whether you want to or not, you register the subtexts of human behavior, you feel it and want to make sense of that feeling, and ultimately want to figure out a way to connect with others over it. Writing is an act of communion, and to pretend otherwise seems to me an unfortunate kind of self-protection.

So then what to do with it? If I were giving easy advice to whoever asked this, I’d probably say to take the compliment on face value, don’t second-guess it, don’t fall down that rabbit hole. Say thank you. Smile. Appreciate the gesture. But I know my own experience has nothing to do with that. (I recently asked my mother to stop forwarding her friends’ reactions to my book—which were all super nice!—which then made me feel worse about it and has left me feeling like I should apologize to her. So sorry, Mom. That was mean. I know you just want to send the nice ones, to share the good news, so you can keep sending them, I’m weird.) In reality I find that I actually have two competing impulses when I feel exposed: one is to curl into a ball and hope to disappear, and the other is to do the opposite, to reach out and be more social, to court interaction and opinion and compose (ahem) overly personal blog posts, to open up further, and go to other people, to trust. This is the only thing that ever really makes me feel better.

And maybe every piece of writing is an act of trust. I can’t help but feel like the more you put out there, the less it feels like you’re walking around midtown Manhattan naked, in winter, during rush hour, but I have a feeling seasoned writers might disagree with that. Maybe you just get used to the air on your junk. If there’s one thing I’ve come to see as inaccurate, though, it’s the easy characterization of writers as a field of wilting lilies, as an enterprise populated by fragile egotists secretly yearning for approval. Because most of exposure, of course, takes courage. Writing through doubt takes a ton of courage. And the best response to your work, perhaps the only thing that, for me, ever really feels good, isn’t a compliment but deep consideration. Evidence of another mind, of another person, with me in the dark.

Have a question for Ted Thompson, Debut Novelist? Drop it in our Ask Box!

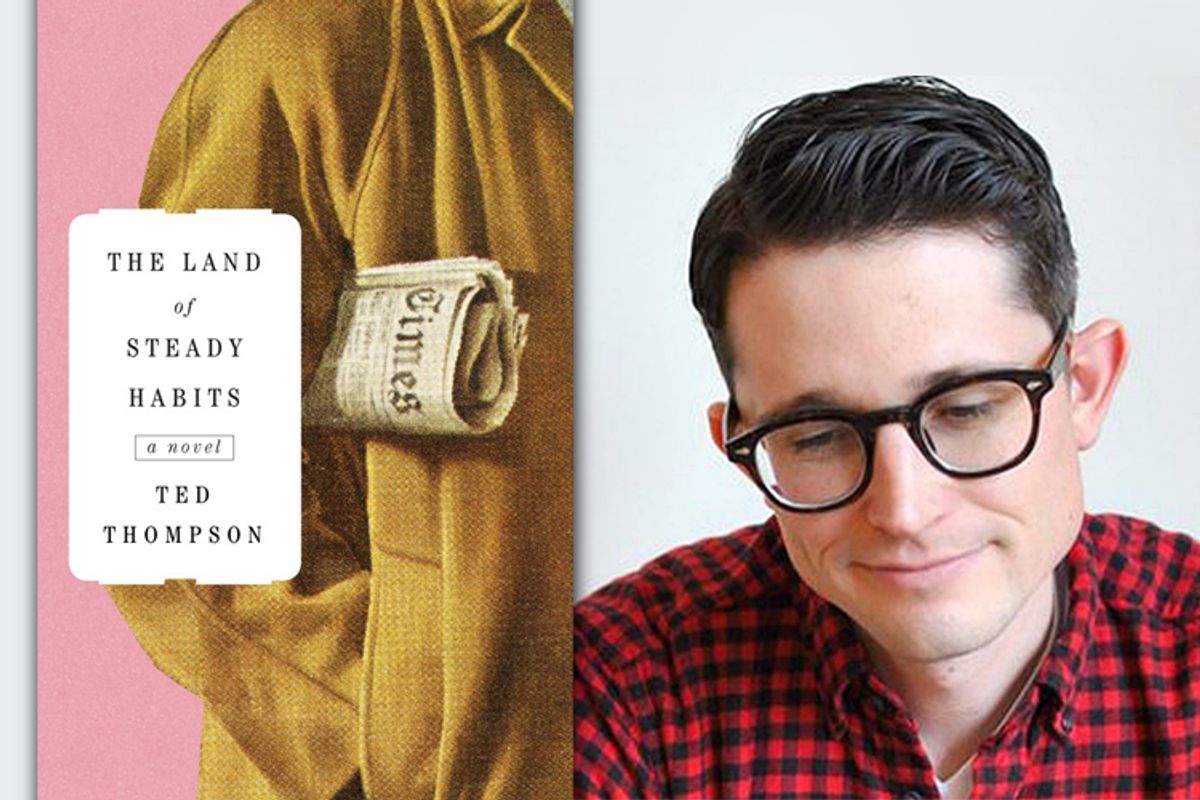

Ted Thompson is the author of the novel "The Land of Steady Habits." He answers questions about being a debut novelist here. Previously published on the Little Brown Tumblr.

Shares