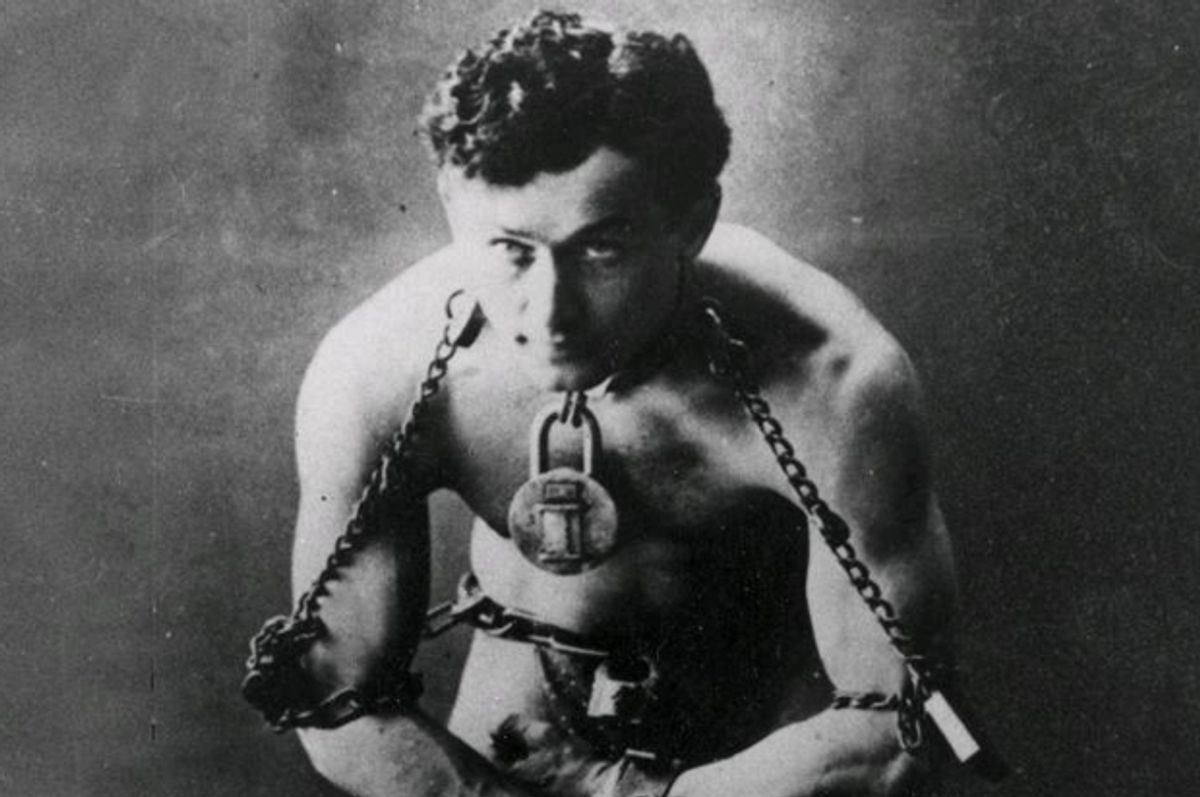

There are two take-aways from the largest auction of Harry Houdini memorabilia in a decade—it netted over $500,000— that happened recently at Potter and Potter auction house in Chicago. The first is that in our decidedly unmagical age, Americans are more fascinated than ever by the great twentieth-century escape artist. There is plenty of evidence for my theory besides the auction, including, beginning this past Monday, the History Channel miniseries starring Adrien Brody as Houdini. (Other high-profile projects near launch date include a Broadway musical supposedly starring Hugh Jackman as Houdini and a book about the escape artist’s relationship with the psychic Margery by the screenwriter David Jaher.)

The allure of Houdini should not be surprising. Since his death in 1926, the escape artist has never been out of fashion. As Adrien Brody put it in a TV interview, Houdini resonated with immigrants trying to achieve the American Dream. His achievements touch nearly every important domain of the twentieth century, including aviation and cinema.

But there is one irritating thing about Houdiniana today that also dates back to his life: the code of secrecy mystifying his tricks. Today this code is alive and well, as was proven by Brody, who apologized last week for the History Channel’s decision to reveal a few how-he-did-it type things on their series.

Which brings me to my second Houdini take-away: it’s time to end the reflex of keeping these tricks secret—perpetrated most forcefully among the small group of magicians and magic collectors that in my darker moments I call the Houdini Industrial Complex.

“There’s probably about 1,000 people who collect Houdini world-wide,” said Jim Matthews, who sold Houdini’s rare 67 page manuscript on witchcraft for $15,000, told me. Those 1,000 have, you could say, magical influence.

Part of me admires the HIC’s commitment to keeping magic’s secrets in an era better known for sock puppets, catfishing, and trolling. But part of me believes that it misses the point entirely. In the twenty-first century, it’s not how Houdini did it that matters. It’s who he was.

In the most recent clashes over spilled secrets, the magicians come off as more shrill than sensible. I’m thinking of the angry reviews of Alex Stone’s sloppy 2011 tell-all magic memoir, "Fooling Houdini," or Ricky Jay’s occasional surliness when my friend Allen Edelstein’s compelling 2013 biopic gets closer than he would like.

The day after the auction, as I paged through the lavish color catalog given to me by Gabe Fajuri, the knowledgeable president of Potter and Potter, I marveled that nearly ninety years after Houdini’s death, 286 lots including rare scrapbooks, unseen manuscripts, a transcript of the 1902 German trial, the coat worn by Houdini’s wife, Bess, crumpled, yellowing papers, garish show biz posters, explanations of tricks (with diagrams) and a sweat-stained “punishment suit”— a knee-length long straitjacket— sold, often for thousands of dollars.

Super-collector Arthur Moses, who owns over 5,000 Houdini items, flew in from Fort Worth, Texas, to bid. He was forthcoming about his get, which included a rare candid photo of the Houdinis in Monte Carlo. “[Houdini] was a complicated man with an intense drive,” he explained via email.

Another Texan to make the trip to Chicago was Jim Baldauf, who was selling a coat worn by Houdini’s wife, Bess, in 1905. He had received it at age ten from an octogenarian magician and acrobat. “I do not believe it should be in a private collection,” he said, although that is likely where it ended up.

Fajuri told me that many bids were placed via Internet, which only a few years ago, I imagined would break the magicians’ code of silence. That has not happened.

Although the Internet has created a new generation of amateur Houdini buffs, like John Cox, who runs the well-informed blog, Wild About Harry, it has not made transparency the norm. Cox disapproves of revealing the secrets of Houdini tricks, or any tricks really. “I don’t think it should be done,” he said.

Neither did Potter and Potter’s Gabe Fajuri. But Fajuri also quoted the magic writer Jim Steinmeyer, “Magicians guard an empty safe.”

Fajuri means that keeping secrets isn’t what magic is about. And he’s right.

Besides outliers like David Blaine, magicians are no longer part of the mainstream cultural conversation. And unlike burlesque, a twentieth century pop culture fad that has reinvented itself by using the language of gender studies, magic, with its largely male population, doesn’t really appeal to women.

Before last Saturday’s auction, the items creating the most buzz seemed to have appeared out of thin air. One was a scrapbook from 1925 with Houdini’s handwritten notes on the pages. Another was the so-called double fold death defying box, a wooden crate housing the milk can into which Houdini climbed and then somehow leapt out of.

What unites these items is their far-flung backstories. They were never in super-collections, or sold on Ebay stores or in other auctions.

The scrapbook was discovered at a swap-meet in California by Michael Bricker, a property manager and antique dealer who declined to say where he found it or the name of his eBay store. The double fold death defying box was owned by Gary Collins, outside of the inner circle because as a so-called gospel magician, he interpolated Bible stories into his shows.

Collins bought the box in the 1970s from a magic dealer and used it until he retired in 2000. “I was going through my Houdini phase,” he said.

The scrapbook sold for $36,000. The box sold for $55,000, before the auction house premium

Collins and Bricker agreed to talk about their items. Others declined to do so. But one or two people talked about the magic community’s accessibility overall.

Still, any gesture towards access quickly runs into its opposite. The library at the Magic Castle in Los Angeles, archivist Lisa Cousins explains, uses its own “eccentric cataloging system—not Dewey Decimal or Library of Congress”—and is closed to non-magicians. (She rushed to say that it allowed researchers.)

David Copperfield’s Museum and Library of the Conjuring Arts, located somewhere in Las Vegas, claims to be open to researchers as well. But the website makes sending an inquiry difficult. As difficult, in my experience, as finding Copperfield himself. (He did not respond to a query about the Houdini auction.)

The day after the auction, I wandered around Potter and Potter office looking at the Houdini artifacts waiting to be packed up and sent to the people who had paid thousands of dollars for them. The punishment suit hung on the wall, armpit sweat stains darkened the canvas. The coat that Houdini’s wife Bess wore, as tiny as that of a child, hung on a mannequin. It reminded me of Jim Baldauf saying, “She looked like a little girl.”

The death defying double fold box stood in the middle of the room. It looked like a packing crate.

“That’s the point,” Gabe Fajuri said as he heaved off the top so I could gaze inside.

I put my head in and squinted. There was a ring where the milk can stood. The room blurred. That was magic.

I hope other people get to see it.

Shares