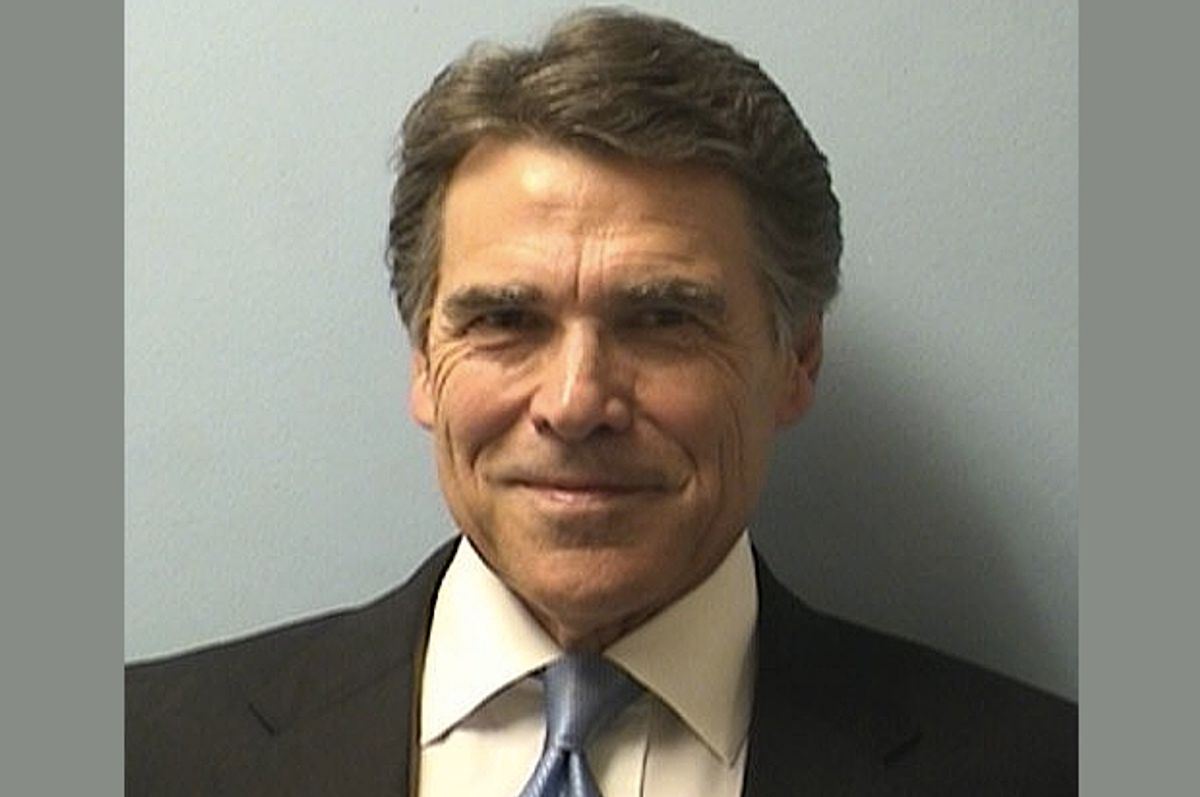

At least in 2012, Rick Perry realized he’d forgotten the name of the federal department he wanted to abolish. But when it comes to the charges he’s just been indicted for, he’s certain of what they are. “Bribery,” he said in New Hampshire recently — but he’s wrong. It’s not exactly a strong position to start from if you’re going to loudly proclaim your innocence. At least he’s got one thing right: “I don’t really understand the details,” he added.

In that, Perry is far from alone. Few, if any, of his high-profile defenders, either left or right, seem to understand much more than he does. Still, you don’t have to be a lawyer to at least have some idea of what’s being charged. The indictment is online for anyone to read, and it’s not that hard to understand -- one count for abuse of official capacity, the other for coercion of a public official. Yet few in the national media seem to have figured that out.

Glenn W. Smith is director of the Progress Texas PAC, so he knows a thing or two about the Lone Star state. He was also part of George Lakoff’s Rockridge Institute, so he’s got a broader intellectual perspective as well — just the combination one would want for a perspective on what’s going on here.

“It was very clear to me that some of the pundits-at-a-distance based their initial opinions on two false assumptions,” Smith said, via email, “1) That the Perry indictments were the product of a nest of angry but unsophisticated Austin liberals; 2) That it was a governor's constitutional power of the veto that was being challenged.”

There are other major points of misinformation, as we'll soon see, but these two do seem to be most central. Smith continued:

Now, here is how a journalist's mind should work (think of a police reporter or any reporter engaged by necessity with daily human messiness). In this instance, faced with the facts that not one but two Republican judges failed to dismiss the criminal complaint against Perry and that an accomplished, conservative special prosecutor had overseen the grand jury indictment, a street-level reporter would think, "There must be more to the game that's afoot than the Perry narrative wants me to believe."

Lacunae are the guiding lights of golden age journalism. This is the practice that leads to "scoops." It is exactly why Woodward and Bernstein's youthful beat experience allowed them to get and keep the lead on Watergate reporting. Their instincts told them there had to be more to the story and they followed their instincts.

Smith’s point is spot on — if you can first spot the holes. Unfortunately, most of the national media seems totally unaware that there are holes in Perry’s narrative. The sharp divide between national and state-level coverage was highlighted in a critical overview at Media Matters, by veteran reporter Joe Strupp (“Texas Journalists Urge National Press to Take Perry Case More Seriously”).

“A very clear divide has arisen in coverage of the Perry indictments,” Strupp told Salon, “with the local Texas media giving the case what appears to be the attention it deserves, and noting it's a valid complaint to at least review and take to trial, given that the grand jury made the decision that it did, while national press or most of the national press is brushing it off to politics, and some kind of perceived payback against Perry.”

As examples of the latter, Strupp’s Media Matters piece cited a high-profile sample:

The New York Times editorial board speculated that it "appears to be the product of an overzealous prosecution." Liberal New York magazine reporter Jonathan Chait labeled the indictment "unbelievably ridiculous." A USA Today editorial dubbed it a "flimsy indictment," while The Wall Street Journal called it "prosecutorial abuse for partisan purposes."

But Strupp also talked with a number of Texas journalists who painted a very different picture, including Jeff Cohen, of the Houston Chronicle, and Keven Ann Willey, of the Dallas Morning News, the state’s two largest dailies, both of which have editorialized in support of seeing the investigation proceed:

The Chronicle wrote that the indictments "suggest that the longest-serving governor in Texas history has grown too accustomed to getting his way when it comes to making sure that virtually every key position in state government is occupied by a Perry loyalist." The Morning News editorial board stated: "It's in every Texan's best interests for the charges against Perry, whatever your view of them, to traverse the entire judicial system as impartially as possible."

Strupp also spoke with Morning News columnist Wayne Slater: “Many reporters in Texas know Perry and are much more familiar with the details in this case, the fact that these are Republicans investigating this and that Perry has a history of hardball politics in forcing people out,” Slater said. “This is a much more nuanced story than some in the Beltway understand."

Indeed, a recent post by Slater, “Why the conventional wisdom in the Rick Perry indictment story might be incomplete,” led early Perry defender David Axelrod to tweet that it was “worth reading” notwithstanding his first impressions.

Key points that Slater and others (including Rachel Maddow, in an Aug. 26 installment of “Debunction Junction”) have raised include:

1) The indictment was not brought by the Tavis County DA. Nor were any other Democrats involved. It’s worth quoting at length from Smith at the Texas Tribune:

Not a single Democratic official was involved at any point in the process, except to recuse him or herself. That’s what the victim of Perry’s “offers,” Travis County District Attorney Rosemary Lehmberg, did. So did District Judge Julie Kocurek.

Kocurek referred the criminal complaint to Judge Billy Ray Stubblefield, a Republican and Perry appointee. Stubblefield could have dismissed the complaint. Instead, he assigned it to Judge Bert Richardson, also a Republican. He, too, could have dismissed the complaint. Instead, he appointed conservative, well-respected former federal prosecutor McCrum as special prosecutor. Republican U.S. Sens. John Cornyn and Kay Bailey Hutchison once recommended McCrum for the job of U.S. attorney for the Western District of Texas. McCrum could have dismissed the complaint. Instead, he took it to a grand jury.

2) The indictment is not an attack on the governor’s right to veto, any more than a bribery charge would be, if Perry were accused of having vetoed a bill in return for a bribe. As Rachel Maddow put it, covering the story the day it broke, “You may have the constitutional right to vote, for example; you don’t have the constitutional right to sell your vote.”

3) Perry’s purported motivation — outrage over Lehmberg’s DWI violation and conviction — was not matched in two other cases where GOP district attorneys were convicted. Nor has he offered any rational explanation why a DWI violation — particularly after rehab — should be seen as so uniquely heinous. Another key Perry talking point has been that “In Texas we settle things with elections.” Why not this time, then?

4) Perry did have a prima facie political motivation to go after Lehmberg: Her office was investigating corruption involving Perry cronies at the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas at the time he sought to force her out, and replace her with his own appointee.

5) The indictment of Perry is not about the “criminalization of politics” — a rhetorical framework that dates back to at least Richard Nixon. As Smith told Salon:

The very term is profoundly disturbing because its real meaning is, "We are the law so it is logically impossible for us to violate it." Political insiders -- from politicians to those who work or used to work for them -- know full well that politics now is little more than institutionalized bribery. How do even well-meaning players cope with that psychologically? They have to set their/our political practices outside the reach of the law.

A good parallel is seen in popular culture presentations of Mob life, in which the wives, sons, daughters of mobsters are willfully blind to the source of their wealth. Anyone who wants to turn on the lights becomes a snitch who wants to "criminalize" their everyday lives.

Of course, none of the above proves that Perry necessarily was guilty. That’s what trials are for. But it does tell us that Perry’s media defense has no relation to known facts, so why should he get the benefit of the doubt in matters where the facts remain unclear? Why shouldn’t a press, whose job it is to be skeptical and hold the powerful accountable, look at Perry like any other politician charged with a crime? Why is there such a gap between the national media and the Texas press?

Strupp isn’t sure. He only knows the gap is there. “I don't know if this is just laziness on the part of the national press side, or, as one person put it to me, ‘a rush to judgment,’ because they want to make it a political story more than possibly a criminal story, but there's definitely a divide, and it seems like the mistake is being made at the national level, because they are not looking at the facts enough.”

MSNBC’s Rachel Maddow has reached the same conclusion. Maddow, you’ll recall, was one of the first to pay attention to Virginia Gov. Bob McDonnell’s money scandals, which now have him standing trial. She was also ahead of the curve in national coverage of Bridgegate. In these and other stories Maddow gave on-air credit to local reporters for bringing the stories to light, and for sticking with them in the face of pushback, so it was hardly surprising that she took the same line in discussing the Perry indictments and how they were being treated.

First off, Maddow set up the out-of-state/in-state divide in a familiar, clear-cut manner (video/transcript):

Rick Perry thinks the felony indictment thing is no barrier to running for president right now. The national media, including the Beltway media, conservative media, and much of the liberal media as well has settled on common wisdom now that the indictment really isn't that big a deal for Rick Perry, that it will have no problem beating the charges. Maybe it will even help him run for president somehow.

But you know what, in Texas the grand jury that indicted him is pushing back on that now, pushing back on it hard saying they took their responsibilities seriously and these indictments indicate a serious and solid case against governor. Texas papers like the Dallas Morning News are editorializing, hey, not so fast, this case is for real, it deserves a real hearing.

In the segment, Maddow interviewed Wayne Slater, discussing some of the major misconceptions floating around, and in conclusion she reemphasized the importance of local reporting in no uncertain terms:

MADDOW: I will say -- as people look at Rick Perry as a potential 2016 contender. You know, he's taking this New Hampshire trip tomorrow, people talk about this indictment. If you're thinking about looking at whether or not Rick Perry is a viable 2016 contender and thinking about looking at these indictments as part of that, get behind the pay wall, right? Pay for subscriptions to the Texas publication of your choice. Start reading Texas papers on this. The coverage is like reading it from Mars when you compare stuff that`s being written in Washington.

Fascinating.

The main point that both Strupp and Maddow were making is neither a new nor an original one. Most of the local reporters in Texas would echo it, and local reporters have most likely been saying as much since the East Eden Times filed its first reports on the Fall. (“Apples? There weren’t any apples. They were pomegranates!”) But the specific dynamics of today’s media require a bit more precision, and that precision was provided by the Atlantic’s James Fallows in his 1996 book, "Breaking the News: How the Media Undermine American Democracy." As I read him, he was describing precisely this same sort of disconnect, between the painstaking, locally grounded, fact-based foundations of journalism, and much more facile, simplified, conflict-centered conventions of corporate journalism in our time, which have proven both less costly to produce, and more lucrative in attracting an audience. So I contacted Fallows to ask if he thought this was an accurate description of what was going on in this instance.

“I used to live in Austin and was aware of some of the twist and turns of the local politics there,” Fallows said. “I haven't myself followed enough of the local coverage to know exactly what's going on, but your basic premise I certainly agree with. And actually, it's a fact that because, precisely because, most national reporters would not have covered, would not be familiar with these kinds of Texas angles, you fit it into the only bed that you as Procrustes have—‘What does this mean for the next election?’ Because there is no development you can't fit into that plot line.”

Given the much wider background of gubernatorial corruption and scandal that I reported on recently, there was another master narrative available, I pointed out, and Fallows concurred, then dug deeper into why campaign narrative held such appeal. “I agree. It's a really interesting point,” he said. “I think the reason that people would generally just be drawn to the campaign narrative theme is you can't be proven wrong,” since it’s always framed in terms of an ongoing flux. “It's like sports talk radio,” Fallows added. “There is not any way that you can ever get in trouble for any of that, so it's the kind of natural thing you want to talk about, and you can’t be wrong. So that’s my cynical interpretation.”

There is, however, another dimension to this story: the reaction of the Democratic establishment. Writing here at Salon on Aug. 25, Michael Lind presented the situation as follows:

The indictment of Rick Perry on felony charges by a Texas grand jury has revealed a split among left-of-center Americans, dividing progressives and Democrats who think the indictment is dubious or worse from others who defend it. The first category includes the New York Times editorial board, Clinton adviser David Axelrod, progressive pundits Jonathan Chait and Matthew Yglesias, Ian Millhiser at the Center for American Progress,Alan Dershowitz and many others, along with yours truly.

Prominent center-left individuals who support the indictment are … well, they aren’t easy to find. To be sure, there are lots of hyperpartisan trolls who hide their identities behind juvenile screen names in comments sections and accuse those of us on the center-left who have raised doubts about the indictment of being shills for Rick Perry or secret conservatives….

Lind seems to have missed Rachel Maddow. He’s also missed the fact that the Democratic establishment has been horribly wrong before, also with criticism being led by “hyperpartisan trolls.” Remember the Iraq War? Endorsed in Senate votes by John Kerry and Hillary Clinton?

Given this relatively recent history, it’s a very odd way to begin laying out his argument. In response to the argument that Republicans were intimately involved in the process that led to Perry’s indictment, Lind purports to show how the Whitewater investigation can be similarly portrayed as nonpartisan. This is not an argument about facts, but about appearances — or at least potential appearances.

Lind does have a very valid point buried in his article: Getting Perry indicted is not a magic bullet for turning Texas blue. But who ever said that it was? After all, everyone knows that Perry’s already leaving office. Lind links this with a much less impressive point — that it will only embolden Republicans to bring trumped-up charges against Democratic governors. This would be an excellent point, if Republican operatives had time machines. How else to explain their successful 2006 conviction of Alabama Gov. Don Siegelman, which a bipartisan group of over 100 former attorney generals argued against in a recent Supreme Court amicus brief?

In the broader sense, Lind is on to something — as Yale law professor Jack Balkin argued in a 1995 paper, populism and progressivism can be seen as broad traditions, encompassing fundamental visions of what democracy means, giving direction to constitutional interpretations, and profoundly influencing our sense of what it means to be an American citizen. At one point, Balkin wrote:

[I]mplicit in the progressivist diagnosis and the progressivist framing of issues is a nascent distrust and critique of popular culture coupled with a call for the state to remedy or at least counteract its deficiencies.

To the extent that Lind, in turn, distrusts this distrust, he and I are on the same side. The fight against corruption has always been one of the hallmarks of progressivism, and those fighting corruption in Texas have discernible roots in that tradition — as one can glean from his article — while Lind’s roots lie with populism. So, if what he’s really arguing for is a renewed primacy of populist concerns, then I would stand with him, especially in Texas.

But populists also have an anti-corruption tradition of their own, so I’m not at all sure there’s a sensible necessary connection here. Moreover, since one of Lind’s greatest concerns is how Republicans can co-opt anti-corruption prosecution strategies, he must also acknowledge how thoroughly right-wing co-optations of populism have already succeeded, both in Texas, and all across America.

Which is why it really is best to keep focused on the facts. Let’s hear them first; only then can we have informed opinions.

Shares