Since President Obama called for military action against the Islamic State last week, Congress has been divided over whether they should just let him proceed using what are really dodgy claims of legal authority, work through some kind of authorization before Congress departs for election season, or oppose such action entirely. (On Wednesday, the House passed a continuing resolution funding the arming of "moderate" Syrian rebels; Thursday, the Senate voted 78-22 to arm them.)

In the face of Congress' growing realization that it should actually do the job the Constitution lays out for them, or cede the authority altogether, Rep. Adam Schiff developed a rather tidy plan to authorize the fight against ISIL. He introduced a bill that repeals the 2002 Authorization to Use Military Force (AUMF) to fight Saddam Hussein immediately. It authorizes fairly circumscribed action against ISIL in Iraq and Syria. And it sunsets both the 2001 AUMF to fight the perpetrators of 9/11 and this new AUMF in 18 months time.

Sen. Tim Kaine has a similar one: It repeals the Iraq AUMF, does nothing with the 2001 AUMF, and sunsets the ISIL AUMF in a year.

Aside from the larger problems with these plans -- such as that they authorize another preemptive war and that no one thinks current military plans against ISIL will work -- they finally get around to cleaning up at least one congressional authorization for war that has been lying around D.C. like a loaded gun for years, one that the Obama administration took out this week and started waving around wildly. It would finally put some boundaries on the war the president could fight and the authorities he could use to do so.

But there's another problem, even assuming we can clean up the stray AUMFs Congress has passed in the last 13 years.

The real festering problem -- worse even than the 2002 AUMF that's been hanging like Chekhov's gun since we withdrew from Iraq in 2011, and the 2001 AUMF that has been stretched beyond recognition, finally, to incorporate a group kicked out of al-Qaida as al-Qaida -- is the September 17, 2001, presidential "finding" authorizing all the really dark aspects of the war against terrorists.

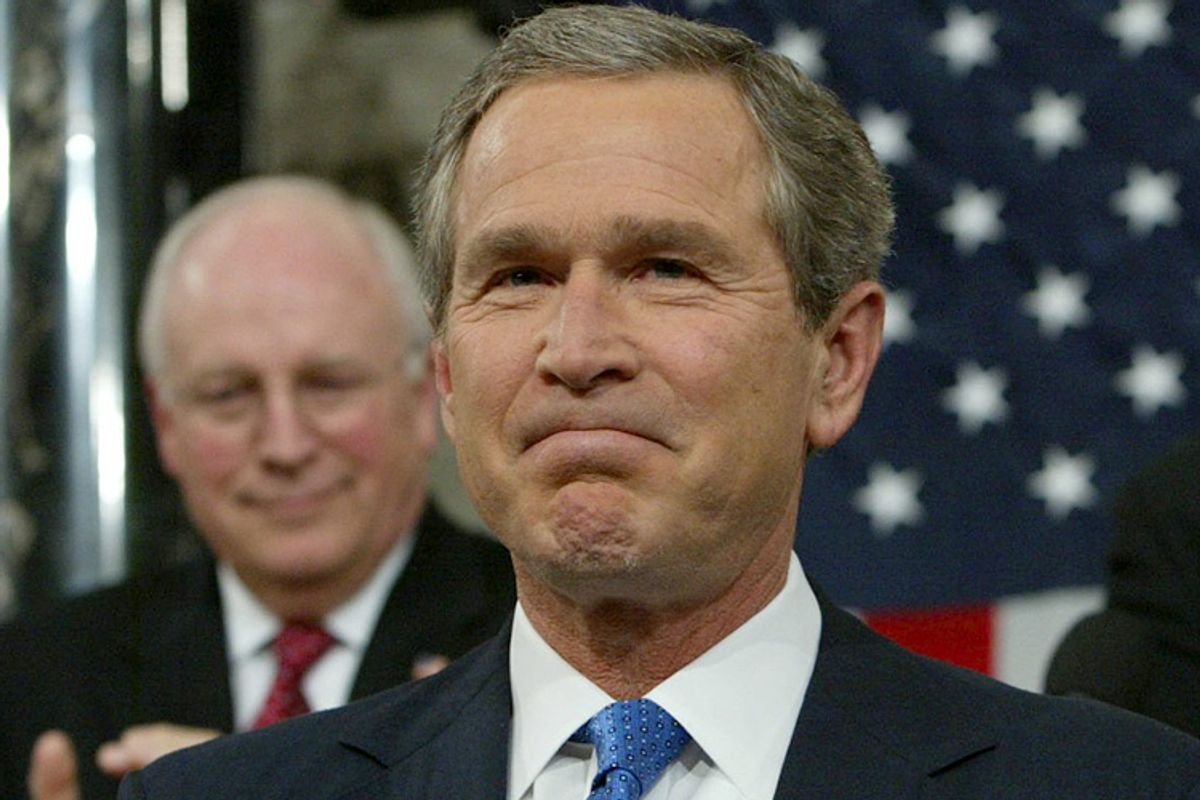

The day before he signed the 2001 AUMF, on Sept. 17, 2001, President George W. Bush issued a "finding" -- I call it the "Gloves Come Off" finding after the phrase then CIA Counterterrorism Center director Cofer Black used to describe the activities included in it -- authorizing a range of covert activities to fight al-Qaida.

A finding (apparently, this was technically an update of a finding that Ronald Reagan used to fight terrorism in the 1980s) is the document the president must send to the intelligence committees in Congress to inform them of an operation CIA or another agency will conduct to affect the politics, economics or military conditions in another country that will be denied by the U.S. Findings are what the government uses, in our democratic country, to give the patina of legitimacy to the potentially scandalous illegal activities our spooks do overseas that we're not supposed to know about.

According to Bob Woodward's "Bush at War," this finding authorized (among other things) heavily subsidizing key intelligence services, like Egypt and Jordan -- so they would do our bidding; working with Libya and Syria -- countries we even then considered pariahs; running paramilitary squads in 80 countries; and using Predator drones to take out top al-Qaida figures.

Oh, and torture.

The Gloves Come Off finding authorized the capture and detention of top al-Qaida figures, and that language was used to justify the entire torture program for some time. By all appearances from public documents, even top intelligence committee members didn't realize the Gloves Come Off finding they had been briefed on authorized torture. In February 2003, for example, then ranking House Intelligence member Jane Harman asked if the president was in the loop on the decision to torture, which she should have known, had she known the finding authorized torture.

The Bush administration told Congress about the Gloves Come Off finding; they simply didn't tell Congress that the "detention" mentioned in the finding meant "torture" until over two years after the program started.

There's even some reason to believe a similar kind of confusion has gone on with one of President Obama's most controversial acts: killing Yemeni-American cleric Anwar al-Awlaki in a drone strike in September 2011. The administration has released four different versions of its justification to kill Awlaki (Feb. 19, 2010, OLC Memo, July 16, 2010, OLC memo, May 25, 2011, White Paper, Nov. 8, 2011, White Paper); the last one before Awlaki's killing explicitly identifies the CIA as the agency that would kill him. But even law professors can't figure out what justification the administration really used to kill an American citizen with no due process. But from what shows up in unclassified form, it appears the administration relied on presidential authority, and we know that the Gloves Come Off finding authorized such drone killings.

As recently as May 2012 -- almost eight months after Awlaki's death -- the Obama administration was still fighting to keep a short mention of the Gloves Come Off finding on a torture document secret. The 2nd Circuit obliged, in part because the administration was still using the finding.

There are several problems with running so much of our war against terrorists using the Gloves Come Off finding (and presumably, some follow-on ones).

One of those was on display at a Senate Foreign Relations Committee on Wednesday. To assess what we should do to combat ISIL, Sen. Tom Udall suggested, the committee should get information on how well a covert effort to arm Syrian rebels to fight Bashar al-Assad has worked. "Everybody's well aware there's been a covert operation operating in the region to train forces, moderate forces, to go into Syria," Udall spoke of the operation publicly discussed as a covert op by Defense Secretary Chuck Hagel a year ago in testimony before the same committee. But Wednesday, even as a new AUMF was at stake, Kerry refused to provide that information. "I know it's been written about, in the public domain that there is, quote, a covert operation," Secretary Kerry said about an operation confirmed as he sat nearby at the same table. "But I can't confirm, deny, whatever." Nor would he explain why the covert op hasn't succeeded. SFRC chair Bob Menendez followed up on Udall's request, complaining that "It is unfathomable to me to understand how this committee" is going to consider responsibly weighing an AUMF, "without understanding all of the elements of military engagement both overtly and covertly."

A number of committees in Congress can't do their jobs given the blind spots created because they're not given briefings on covert ops.

Plus, as Udall's observation makes clear, conducting war as a covert op prevents both members of Congress and the public from assessing the efficacy of the programs; in addition to the Syrian op, the secrecy surrounding both the torture and CIA's drone program have prevented an accurate assessment of whether the programs did what CIA claimed they did.

Moreover, conducting war by covert op seems to lead us to rely on unreliable partners. For example, the Gloves Come Off finding specifically calls for relying on intelligence from partners -- notably, the Saudis, whose responsibility for and interests in the fight against ISIL are suspect -- who may not always share our interests.

Perhaps most problematic, however, the entire structure of a covert op finding sets up a relationship of mutual incrimination between the president and those he authorizes to conduct these illegal actions. The CIA carried out the torture, but the authorization for it came straight from the White House. Once that relationship gets established, each side has an incentive to protect the other, even if that doesn't serve our country's interests.

We've seen it play out, in recent weeks, with the Senate Torture Report where, even in the investigative stages, the CIA withheld documents implicating the White House. No wonder President Obama isn't pushing CIA to declassify everything the Senate thinks should be released; the Agency has done its part to protect the institution of the presidency.

In the weeks ahead, we will continue to debate under what legal terms the president should be able to commit the nation to war in Iraq and Syria. And we will see a heavily redacted summary of the Senate Torture Report, which will show that a presidentially authorized program raged out of control under the cover of lies about its successes.

While the debate you'll hear will focus on yet another AUMF, we need to spend as much time reclaiming Congress' control over that other half of the war, the secret one, where presidents authorize the agencies to do really rash things under cover of secrecy.

Shares