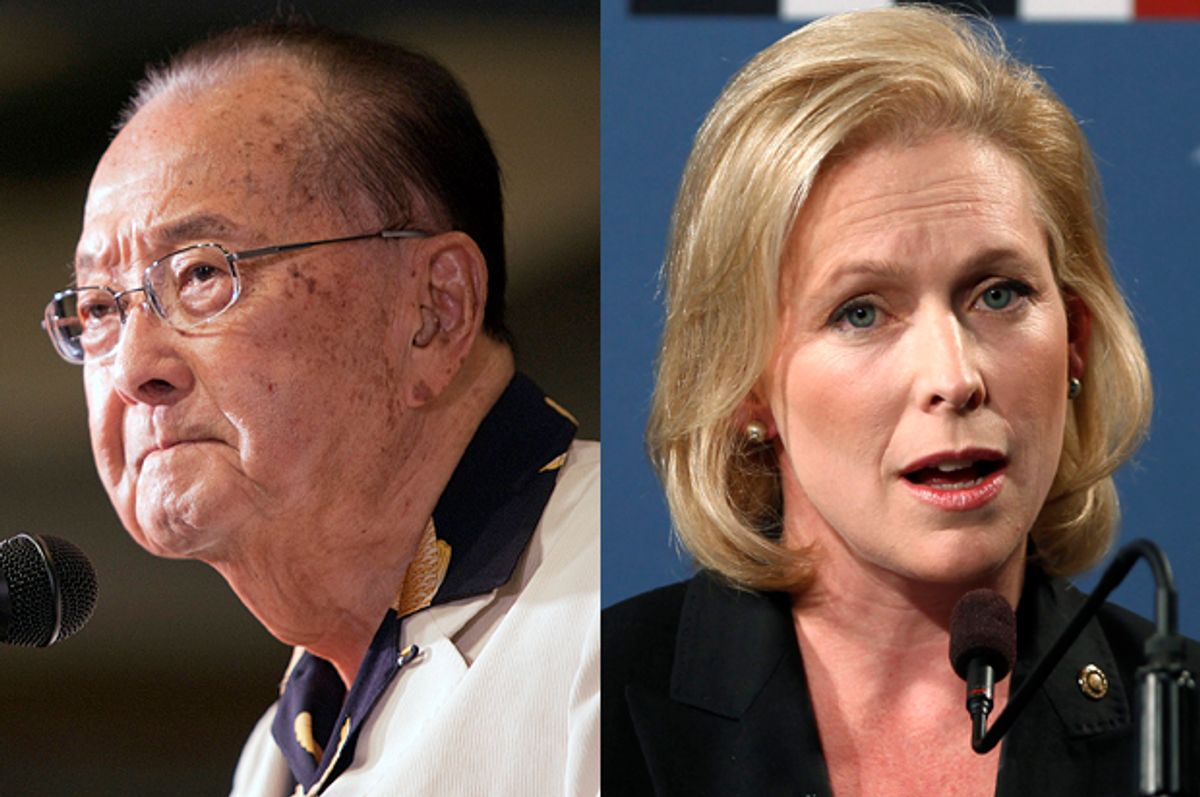

The New York Times launched its new morning politics brief on Monday by "solving a Washington mystery." That mystery happened to be the identity of one of the men who Sen. Kirsten Gillibrand said harassed her after the birth of her second child. According to the Times, the late Daniel K. Inouye, a Democratic senator from Hawaii and the first Japanese American to serve in Congress, was the man who told Gillibrand that she shouldn't lose too much weight because, "I like my girls chubby." As the Times also noted, Inouye, who was celebrated as a champion of women's rights, was also alleged to have sexually assaulted a woman in 1992. After news of the alleged assault broke, nine other women came forward with stories of being sexually harassed by Inouye. None of the women wanted to go forward with their claims.

The Times report likely sated some of the public's curiosity (and it certainly heaped a bit more shame on the muck-brained journalists who accused Gillibrand of concocting the story to score political points), but it also does a few other things. For one, it reminds us that women rarely, if ever, get to control their own narratives. In a series of interviews about her memoir, Gillibrand has maintained that she didn't name names because the point wasn't about some isolated incident of harassment, but a culture of workplace harassment that women face, and the real and daily consequences of that culture.

“I use these illustrations as an example of a much larger point. It’s important to have a debate about how women are treated in the workplace,” she said recently. “I’m not alone in having someone say something stupid. It’s less important who they are than what they said.” So now we have a villain for our story, and that "national debate" has transformed into a conversation about what, if anything, this means for Inouye's legacy.

But the other thing this illustrates, that a civil rights pioneer with a solidly progressive record on issues like reproductive freedom, equal pay and voting rights could also be a man who is alleged to have harassed and assaulted women, is the knotty and complicated truth about violence against women in our culture. That it doesn't fall neatly along ideological lines. That's it's everywhere. The story also also lays bare the strange calculus that women must perform each time they experience abuse or harassment, particularly from men who control, in ways perceived or actual, some power over their lives and careers.

The news about Inouye remains a report, of course. But it's easy enough to understand why Gillibrand would have been hesitant to name him. Calling him out might have come across as slandering a dead man, a decorated war hero. A senator whose election was a historic moment of disruption for the (still) mostly white chamber. The man whose career President Barack Obama said showed him "what might be possible in my own life." In her recollection of the incident in her book, Gillibrand calls the man who harassed her "one of my favorite older members of the Senate.”

What do you do when one of your favorite older members of the Senate tells you that he likes you chubby? And what do you think the response would have been to a young senator coming in and making hay about a beloved member of her own party? Gillibrand made the personal and political ramifications of coming forward clear in a recent interview on HuffPost Live. Referring to a separate incident in which a labor leader told her her that he didn't think she was attractive enough to win statewide election, Gillibrand said, "I wasn’t in a place where I could tell him to go fuck himself.”

Very few women are. Last year, a writer named Monica Byrne wrote about being harassed by Bora Zivkovic, a well-respected editor who ran the blogs at Scientific American and was dubbed the "Blogfather" by his peers. He had a history of sexually harassing the women who came to him looking for career counsel. After Byrne went public with her experience, another science writer named Hannah Waters came forward. Both women shared the same concern about what naming Zivkovic might do to hurt their careers.

Almost every woman I know has a story (or two, or five, or ten) like this. Women whose harassers are well-respected men. "Good guys," always. Sometimes these men are senior colleagues or bosses who are gatekeepers to better positions, introductions, raises. So the "friendly" comments about appearances or sex or attraction may be unwanted, but so too is being ostracized in your field or stalled in your career. Other times these men aren't colleagues, but professors who might write a letter of recommendation. An organizer who holds influence over the movement you're part of. A family friend. A community leader. The list of men who seem beyond reproach is long.

And not all of them wear the typical mask of a villain. Some are progressives, even self-identified feminists. Men who don't vote to strip women of control over their own bodies but who still feel entitlement to those bodies. So this is the face of harassment. The faces of the men you know, and the faces of the men you respect. How do we create space to talk about that? Maybe this is the larger conversation Gillibrand wanted to have when she chose not to name names.

Shares