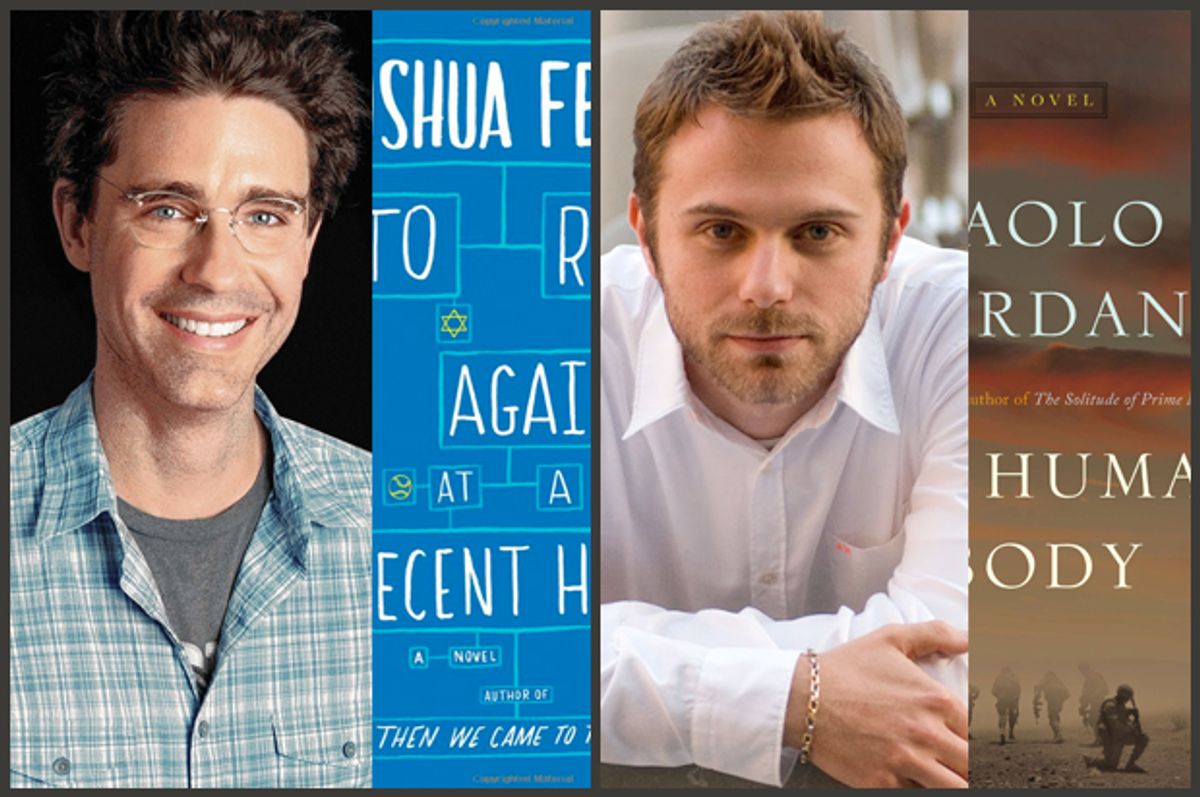

Joshua Ferris: You’ve written a novel about the war in Afghanistan, "The Human Body." What interested you? Did you go to Aghanistan?

Paolo Giordano: Yes, I went to Afghanistan twice, both times as an embedded journalist in the Italian Army. I had no idea I would write a novel about it. The first time I only had in mind an article for Vanity Fair, which I later published. The second time, one year later, I had half of the book done.

I know that you’ve had a general interest in war for a long time, and in what art can be made from the material of war. What compels you toward war as a subject matter? Does art redeem some measure of war’s misery?

I’m not sure it can redeem it. I’m afraid not. But there seems to be a deep connection between war and literature. Somehow, narration as we know it started with war. Think of Homer, for instance. But what mattered most for me was my personal attraction to it. Most of the novels of the last century which I loved are strongly related to war. I couldn’t really understand why, so I thought I should find out. The one book that eventually pushed me to search for a “living” war was Norman Mailer’s The Naked and the Dead. After I read it and felt so personally and mysteriously shaken, I decided to go to Afghanistan.

How committed were you to capturing the real experience of war and to what extent did you depart from reality to create the world of the book? I guess another way of asking this is: though you’re writing fiction, did you feel an obligation to truth, given the subject matter?

A big effort was to get rid of that obligation. I didn’t intend to write a realistic novel and I think I haven’t. I took only the elements of reality that could serve my purposes of symbolization. That’s why I chose a small, forgotten Forward Operating Base: It had to be isolated from the overall context like a womb. But I admit it’s very difficult to emancipate yourself from realism when you’re writing about something that’s still happening and that’s normally the exclusive domain of the news. You need to forget all that ready-at-hand imaginary and create your own.

The title of the book diverts attention from a massive theater of war toward something smaller, the individual bodied person. What is the relationship between the two in the book, the big war on the one hand and the single body on the other?

One of the things that struck me the most when I was living with the soldiers was how vulnerable and exposed their bodies looked to me, even when they were dressed with uniforms and armed from head to toe. Most of them were so shockingly young. I found that very moving. Also, the germinal image for the novel came from a horrific episode a captain told me one night. He had to literally collect pieces of his men from the ground after an ambush. I couldn’t get rid of that image and it lived with me for the two years of the writing. Something very similar to that happens late in the novel.

You ask big questions by portraying intimate lives. Your first book, The Solitude of Prime Numbers, did this by confining itself to two characters. But books about war naturally tend to include an ensemble cast, as does this one. Was that a willful expansion of your artistic range, or a simple obedience to the form?

It was both. When I first began to write about war, my first instinct was to write not about single characters, but about a compact group, a multitude. My eye was not used to seeing subtlety; it could only see a crowd of young men, all dressed in the same way, all with the same haircut, etc. Some of the hardest work was the slow process of isolating one character from the crowd, and then another, and then another, and building the world inside each of them.

One of my favorite characters in the book is First Corporal Major Angelo Torsu. Whatever can go wrong with a man’s body during wartime does go wrong with poor Torsu. Did you conceive of him as I read him, as a creature of myth?

I’m afraid I based him on myself. Not that I experienced the worst things that happen to him, but that chain of small breakdowns suffered when you’re away from home, the banes that make you feel worried and alone and desperate, I’ve been through that. I extrapolated those personal experiences to their most tragic limit.

The global unpopularity of the war in Afghanistan points a finger at America, and it’s sometimes easy to forget that we weren’t the only ones fighting. But in fact, your country sent soldiers to Afghanistan, as did many others. Let me ask you a few questions for the sociologically minded. Was the country divided over the war? What is its legacy in Italy? And what is the country’s relationship with its soldiers?

I have the impression that the American and European perspectives on these Middle East wars are quite different. Somehow, it seems that, as Europeans, we follow someone else’s decisions. We’ve been in Afghanistan all this time (and in Iraq before that) only because we couldn’t help but be there. Our national objectives in the conflict aren’t clear to anybody, and even less to the soldiers who fight. So the tendency is to hide these real wars under the fake name of “peace missions” and to build thick clouds of hypocrisy around them.

The mission of course still divides the population but, to speak rather frankly, the general interest is dramatically low and only flares again, briefly, when one of our soldiers dies. This reflects a general indifference, if not a slight intolerance, of people toward the Army in general. And that is for sure very different from the U.S. situation.

All of your characters have complicated home lives. Some seem better off in Afghanistan than in Italy. Take Ietri, for instance, smothered by his mother’s oppressive love. Do you, Paolo Giordano, have mommy issues?

Who doesn’t? Add the fact that I’m Italian, the Country of Moms.

When I think about these characters and their complicated home lives, I think of Lieutenant Alessandro Egitto. He’s your most poignant and complicated character. What compelled you to write select scenes from his first-person perspective, which I found among the book’s most moving passages?

These first-person incursions came quite late in the process. I felt like there was some distance between me, my personal life and feelings, and the war scenery. I needed a stronger connection between the two. So I started to think about war in a wider sense, about the many ways in which war is incarnated in our everyday lives, even when we don’t recognize it as war. Through Alessandro Egitto and his past, I brought the dynamics of war down to its most fundamental unit: a family of four.

From the prologue we know that Egitto can’t leave the war behind, nor can he quit the military. He’s an archetype, the military lifer, a man defined -- and confined -- by his career. Does this resonate in some way personally?

I think we all get somehow trapped by our jobs, by the definition we choose for ourselves at some point. The novel is a lot about how difficult it is - perhaps impossible - to build a new idea of oneself. That requires a lot of strength and some amount of destruction. Egitto is eventually free from his family story, but not from the military life.

There’s a finely wrought fight scene in the latter part of the book, and while it’s tense & upsetting, it’s also fun. Was it fun to write, or something more complicated? Why do we get so high on war narratives when there’s so much death?

I wrote that part very quickly, quicker than anything else in the book. And I didn’t have to revise it again, which is usually the case. I came to that part of book ready as a bullet. And I guess that the fact that we get so high when we come close to death and danger, even when it’s only in a novel or a movie, is really the reason why war is so attractive to anybody and unfortunately will always be. There is a James Hillman essay that explains all of this very clearly. Its title says it all: “A Terrible Love of War.”

This is your second book to come out in the States, but in Italy you’ve already published a third book, and you’re still a very young man. What’s going on with you?

Fear. Time running out. But the third book is not really a novel. It’s a long short story.

You and I gave a reading in Rome earlier this year, and afterwards, I watched as you were swarmed by young girls and old men alike, all clamoring for your attention. How does it feel to be an international rock star who’s making writing cool again?

None of that is real. You know it. I wish it were, young girls and old men alike and all. But it isn’t.

Shares