In the aftermath of the Michael Brown shooting, there was a brief moment when much of America was forced to look at an inconvenient truth about ourselves and the scope of advances we've made in race relations. Most of the discussion took place around the statistics (or lack thereof) around police shootings, specifically of African-Americans, for obvious reasons. We talked about the militarization of the police in the wake of the overreaction to the protests. And there was some acknowledgment of the oddness of the city government of Ferguson, Missouri, being overwhelmingly white when the population of the city was majority black. But there wasn't a whole lot of talk about this:

St. Louis, recently ranked as the sixth most racially segregated city in the country, has entrenched polarized attitudes about race and law enforcement.

Ferguson, a community of 21,000, is an inner-ring suburb, a place where it's easy for the economic recovery to bypass the poor. It's a city of 6 square miles, about 10 miles north of downtown. About two-thirds of the residents are African-American. The median income is $37,000, roughly $10,000 less than the state average. Nearly a quarter of residents live below the poverty level, compared with 15 percent statewide.

It's part of north St. Louis county, where whites left en masse beginning over the past few decades. In the '60s, they began rapidly leaving north city, creating one of one of the most extreme cases of "white flight" in the country.

I think many white people are surprised by the fact that actual, literal segregation still exists in America. After all, we had a big kumbaya moment more than 40 years ago and passed the Fair Housing Act, which made it illegal to discriminate in housing on the basis of race. And it's true that we are a long way from the days of Jim Crow. Still, the facts are the facts and America remains segregated. to a much higher degree than many realize. There are a lot of reasons for that, not the least of which is poverty.

But it used to be much, much worse. And the reason for the improvement is not because we all just woke up one morning and decided that our immoral, unprincipled racism was a great big no-no. It happened because the civil rights movement created a critical mass for legislative change like the Civil Rights Act, the Voting Rights Act and the Fair Housing Act, all of which were preceded by various court rulings that served to loosen the grip of racist policies that were firmly entrenched throughout the U.S. And it was not easy.

In his epic history of the 1960s, "Nixonland," Rick Perlstein observed something that few people remember: The price was very, very high for politicians who backed these civil rights laws and that's because there was a furious white backlash. It's common knowledge that some of that backlash was formed by the urban riots of the period. But there was something else, which he explored in greater depth in this article:

[Whites were in] terror at the prospect of the 1966 civil rights bill passing, which, by imposing an ironclad federal ban on racial discrimination in the sale and rental of housing—known as"open housing"—would be the first legislation to impact the entire nation equally, not just the South.

He recounts the confrontations that took place in Chicago, then the most segregated city in America, in "Nixonland":

You could draw a map of the boundary within which the city's seven hundred thousand Negroes were allowed to live by marking an X wherever a white mob attacked a Negro. Move beyond it, and a family had to face down a mob of one thousand, five thousand, or even (in the Englewood riot of 1949, when the presence of blacks at a union meeting sparked a rumor the house was to be"sold to niggers") ten thousand bloody-minded whites. In the late 1940s, when the postwar housing shortage was at its peak, you could find ten black families living in a basement, sharing a single stove but not a single flush toilet, in"apartments" subdivided by cardboard. One racial bombing or arson happened every three weeks.... In neighborhoods where they were allowed to"buy" houses, they couldn't actually buy them at all: banks would not write them mortgages, so unscrupulous businessmen sold them contracts that gave them no equity or title to the property, from which they could be evicted the first time they were late with a payment.

He published some of the constituent letters he found hidden in the archives of a congressman who lost his seat in 1966 over civil rights, protesting those "Open Housing" provisions in the bill before the Congress. Here's just one example:

I am white and am praying that you vote against open housing in the consideration of Equal Rights. Just because the negro refuses to live among his own race--that alone should give you the answer. I was forced to sell my home in Chicago ('Lawndale') at a big loss because of the negroes taking over Lawndale--their morals are the lowest (and supported financially by Mayor Daley as you well know)--and the White Race by law. Please don't take away our bit of peace and freedom to choose our neighbors. What did Luther King mean when he faced the nation on TV New Year's day--announcing he will not be satisfied until the wealth of America is more evenly divided? Sounds like Communism to Americans. 'Freedom for all'--including the white race, Please!

Martin Luther King and his fellow marchers were met with vicious anger, hostility and violence from whites in Chicago that summer culminating in MLK making his famous quip, "I think the people of Mississippi ought to come to Chicago to learn how to hate." It was very, very ugly.

Interestingly, some progress continued despite the backlash. Perhaps the momentum was too strong to stop it. In 1968, Lyndon Johnson persuaded a fractious Congress to pass the Fair Housing Act, which included a mysterious provision called the "disparate impact rule." That rule has turned out to be a bedrock requirement for enforcing fair housing rules (to the extent they've been able to enforce them) because it basically holds that you don't have to be a Confederate flag-loving racist to discriminate.

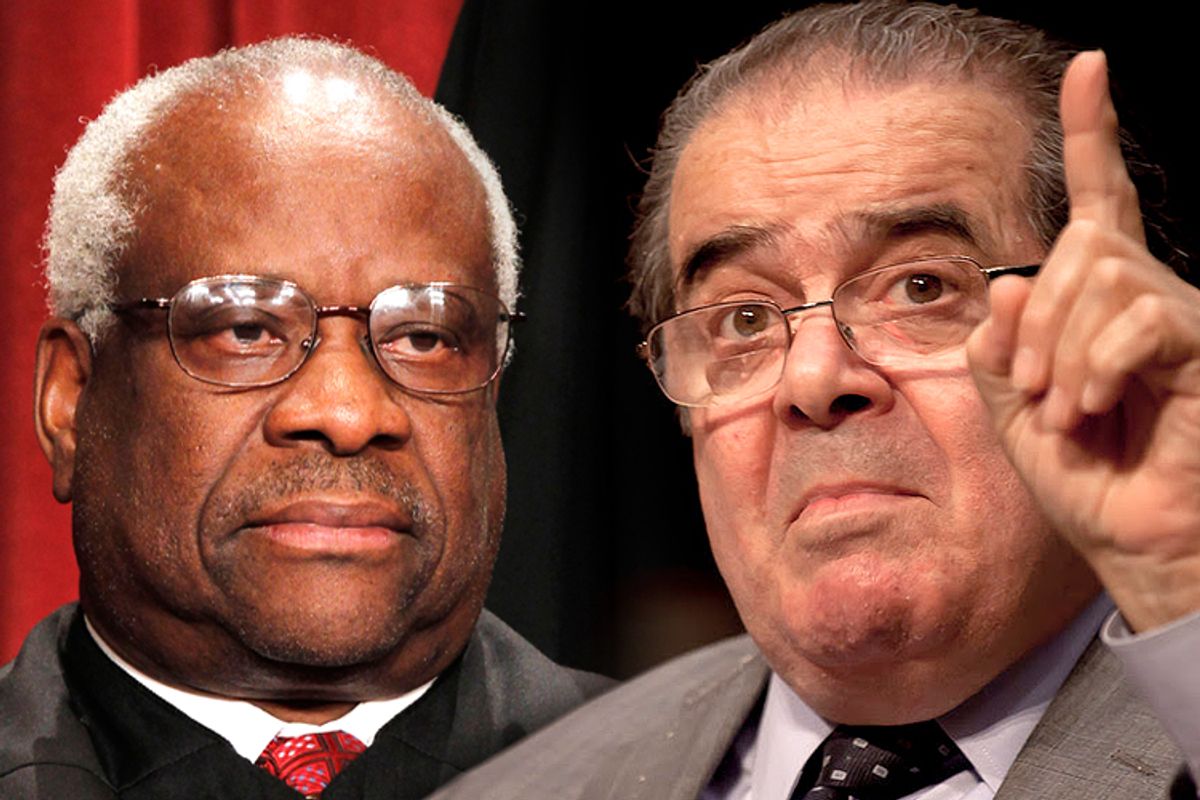

Unfortunately, our right-wing Supreme Court just accepted a case that challenges this important tool to fight discrimination and it's fair to say that many people are not optimistic about its chances of survival. And that's going to be a problem.

Jamelle Bouie explained why in this terrific piece in Slate:

Another way to understand disparate impact is this: It’s a way to confront the realities of racial inequality without trying to prove the motivations of an institution, organization, or landlord. In housing especially, it’s rare to get someone as explicit about his discrimination as Donald Sterling. More often, you must look for patterns of unequal results or unfair treatment that stem from “objective” or “neutral” criteria.

In United States v. Wells Fargo, for example, the Department of Justice sued the mortgage lender over its role in the subprime market. According to the suit, Wells Fargo brokers raised interest rates and fees for more than 30,000 minority customers, and encouraged black and Hispanic homeowners to take subprime loans even if they qualified for traditional financing. We don’t know if malice drove this policy, but under disparate impact guidelines, it doesn’t matter: The government can show concrete harm and act accordingly.

Without the power to do that, it's going to be very difficult for the government to enforce fair housing laws.

Bouie makes a powerful historical observation in his piece in which he points out that laws to expand civil rights in this country have been watered down by backlash politics ever since the Civil War. He points out that as far back as 1883, we were hearing arguments like this from the Supreme Court as they ruled on cases stemming from the 1875 Civil Rights Act:

When a man has emerged from slavery, and by the aid of beneficent legislation has shaken off the inseparable concomitants of that state, there must be some stage in the progress of his elevation when he takes the rank of a mere citizen, and ceases to be the special favorite of the laws, and when his rights as a citizen, or a man, are to be protected in the ordinary modes by which other men’s rights are protected.

As we know, Jim Crow continued for nearly a century after that petulant observation. And now we are in the midst of yet another round, a continuation of that second backlash to the civil rights movement that began in cities like Chicago back in 1966. And once again African-Americans are having to take to the streets to demand their rights. And so it goes.

Shares