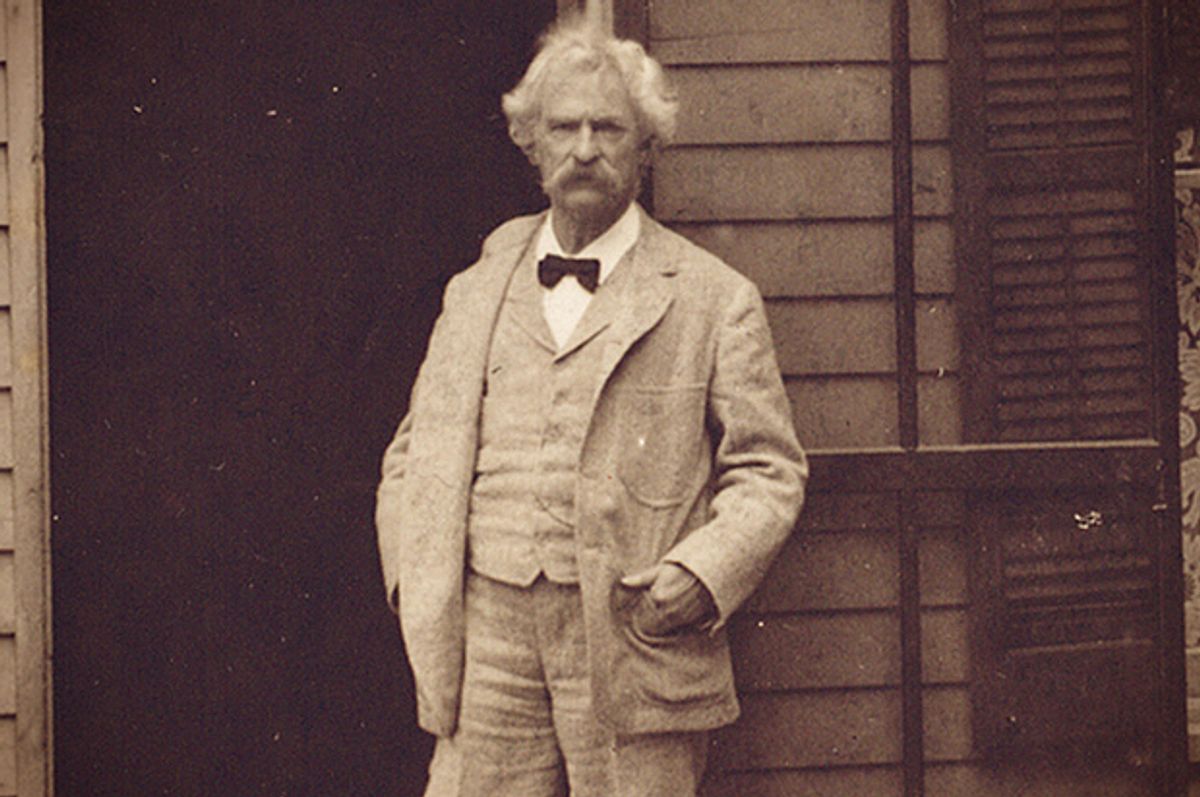

Mark Twain undertook the project of an autobiography in 1870 at the age of thirty-five, still a young man but already established as the famous author of "Innocents Abroad" and confident that he could navigate the current of his life by drawing upon the lessons learned thirteen years earlier as a steamboat pilot on the Mississippi River. As he noted in "Life on the Mississippi,"

There is one faculty which a pilot must incessantly cultivate until he has brought it to absolute perfection. . . . That faculty is memory. He cannot stop with merely thinking a thing is so-and-so, he must know it. . . . One cannot easily realize what a tremendous thing it is to know every trivial detail of twelve hundred miles of river and know it with absolute exactness.

Twain expected the going to be as easy as a straight stretch of deep water under the light of a noonday sun. It wasn’t. His memory was too close to absolute perfection, and he soon ran across snags and shoals unlike the ones to which he was accustomed south of Memphis and north of Vicksburg, an embarrassment he admitted in 1899 to a reporter from the London Times: “You cannot lay bare your private soul and look at it. You are too much ashamed of yourself. It is too disgusting.”

But Twain doesn’t abandon his attempt at autobiography, because the longer he stays the course—for thirty-four years and through as many drafts of misbegotten manuscript while also writing nine other books, among them Huckleberry Finn—the more clearly he comes to see that what he intends is not the examination of an inner child or the confessions of a cloistered id. His topic is of a match with that of the volume here in hand—America and the Americans making their nineteenth-century passage from an agrarian democracy to an industrial oligarchy, to Twain’s mind a great and tragic tale, and one that no other writer of his generation was better positioned to tell because none had seen the country at so many of its compass points or become as acquainted with so many of its oddly assorted inhabitants.

Born in Missouri in 1835 on the frontier of what was still Indian territory, Twain as a boy of ten had seen the flogging and lynching of Negro slaves, had been present in his twenties not only at the wheel of the steamboats Pennsylvania and Alonzo Child but also at the pithead of the Comstock Lode when in 1861 he joined the going westward to the Nevada silver mines and the California goldfields, there to keep company with underage murderers and overage whores. In San Francisco he writes newspaper sketches and satires, becomes known as “The Wild Humorist of the Pacific Slope” who tells funny stories to the dancing girls and gamblers in the city’s waterfront saloons.

Back east in the 1870s, Twain settles in Hartford, Connecticut, an eminent man of letters and property, and for the next thirty years, oracle for all occasions and star attraction on the national and international lecture stage, his wit and wisdom everywhere a wonder to behold—at banquet tables with presidents Ulysses S. Grant and Theodore Roosevelt, in New York City’s Tammany Hall with swindling politicians and thieving financiers, on the program at the Boston Lyceum with Oliver Wendell Holmes, Horace Greeley, Petroleum V. Nasby, and Ralph Waldo Emerson. He also traveled forty-nine times across the Atlantic, and once across the Indian Ocean, as a dutiful tourist surveying the sights in Rome, Paris, and the Holy Land; as an itinerant sage entertaining crowds in Australia and Ceylon.

Laughter was Twain’s stock-in-trade, and he produced it in sufficient quantity to make bearable the acquaintance with grief he knew to be generously distributed among all present in a Newport drawing room or a Nevada brothel. Whether the audience was drunk or sober, swaddled in fur or armed with pistols, Twain recognized it as likely in need of comic relief. “The hard and sordid things in life,” he once said, “are too hard and too sordid and too cruel for us to know and touch them year after year without some mitigating influence.” He bottled the influence under whatever label drummed up a crowd—burlesque, satire, parody, sarcasm, ridicule—any or all of it guaranteed to fortify the blood and restore the spirit.

Twain coined the phrase the “Gilded Age” as a pejorative, to mark the calamity that was the collision of the democratic ideal with the democratic reality, the promise of a free, forbearing, and tolerant society run aground on the reef of destruction formed by the accruals of vanity and greed that Twain understood to be not a society at all but a state of war. The ostrich feathers and the mirrored glass, he associated with the epithet citified, “suggesting the absence of all spirituality, and the presence of all kinds of paltry materialisms and mean ideals and mean vanities and silly cynicisms.” His struggling with his own paltry materialisms further delayed the composition of the autobiography. For thirty-four years he couldn’t get out of his own way, kept trying to find a language worthy of a monument, to dress up the many manuscripts in literary velvets and brocades.

Eventually faced with the approaching sandbar of his death, he puts aside his pen and ink and elects to dictate, not write, what he construes as his “bequest to posterity.” He begins the experiment in 1904 in Florence, where he has rented a handsome villa in which to care for his cherished, dying wife. To William Dean Howells, close friend and trusted editor, he writes to say, “I’ve struck it!” a method that removes all traces of a style that is “too prim, too nice,” too slow and artificial in its movement for the telling of a story.

“Narrative,” he had said at the outset of his labors,

should flow as flows the brook down through the hills and the leafy woodlands . . . a brook that never goes straight for a minute, but goes, and goes briskly, and sometimes ungrammatically, and sometimes fetching a horseshoe three-quarters of a mile around and at the end of the circuit flowing within the yard of the path it traversed an hour before; but always going, and always following at least one law, always loyal to that law, the law of narrative, which has no law. Nothing to do but make the trip; the how of it is not important so that the trip is made.

Twain’s wife does not survive her season in the Italian sun, and at the age of seventy-one soon after his return to America, he casts himself adrift on the flood tide of his memory, dictating at discursive length to a series of stenographers while “propped up against great snowy white pillows” in a Fifth Avenue town house three blocks north of Washington Square. He delivers the deposition over a period of nearly four years, from the winter of 1906 until a few months before his death in the spring of 1910, here and there introducing into the record miscellaneous exhibits—previously published speeches, anecdotes and sketches, newspaper clippings, brief biographies, letters, philosophical digressions, and theatrical asides.

The autobiography he offers as an omnium-gatherum, its author reserving the right to digress at will, talk only about whatever interests him at the moment, “drop it at the moment its interest threatens to pale.” He leaves the reader free to adopt the same approach, to come across Twain at a meeting of the Hartford Monday Evening Club in 1884 (at which the subject of discussion is the price of cigars and the befriending of cats) and to skip over as many pages as necessary to find Twain in Honolulu in 1866 with the survivors of forty-three days at sea in an open boat, or discover him in Calcutta in 1896 in the company of Mary Wilson, “old and gray-haired, but . . . very handsome,” a woman whom he had much admired in her prior incarnation as a young woman in 1849 in Hannibal, Missouri:

We sat down and talked. We steeped our thirsty souls in the reviving wine of the past, the pathetic past, the beautiful past, the dear and lamented past; we uttered the names that had been silent upon our lips for fifty years, and it was as if they were made of music; with reverent hands we unburied our dead, the mates of our youth, and caressed them with our speech; we searched the dusty chambers of our memories and dragged forth incident after incident, episode after episode, folly after folly, and laughed such good laughs over them, with the tears running down.

The turn of Twain’s mind is democratic. He holds his fellow citizens in generous and affectionate regard not because they are rich or beautiful or famous but because they are his fellow citizens. His dictations he employs as “a form and method whereby the past and the present are constantly brought face-to-face resulting in contrasts which newly fire up the interest all along like contact of flint with steel." Something seen in Paris in 1894 reminds him of something else seen in Virginia City in 1864; an impression of the first time he saw Florence in 1892 sends him back to St. Louis in 1845.

The intelligence that is wide-wandering, intuitive, and sympathetic is also, in the parsing of it by Bernard De Voto, the historian and editor of Twain’s papers, “undeluded, merciless and final.” His comedy drifts toward the darker shore of tragedy as he grows older and loses much of his liking for what he comes to regard as “the damned human race,” his judgment rendered “in the absence of respect-worthy evidence that the human being has morals.”

Twain doesn’t absent himself from the company of the damned. He knows himself made, like all other men, as “a poor, cheap, wormy thing . . . a sarcasm, the Creator’s prime miscarriage in invention, the moral inferior of all the animals . . . the superior to them all in one gift only, and that one not up to his estimation of it—intellect.” The steamboat pilot’s delight in that one gift holds fast only to the end of his trick at the wheel of his life. Mankind as a species he writes off as a miscarriage in invention, but he makes exceptions—a very great many exceptions—for the men, women, and children (usually together with any and all of their uncles, nieces, grandmothers, and cousins) whom he has come to know and hold dear over the course of his travels. The autobiography is crowded with their portraits sketched in an always loving few sentences or a handsome turn of phrase. Humor is still “the great thing, the saving thing after all,” but as the gilded spirit of the age becomes everywhere more oppressive under the late-nineteenth-century chandeliers, Twain pits the force of his merciless and undeluded wit against “the peacock shams” of the world’s “colossal humbug.” He doesn’t traffic in the mockery of a cynic or the bitterness of the misanthrope. Nor does he expect his ridicule to correct the conduct of Boss Tweed, improve the morals of Commodore Vanderbilt, or stop the same-day deliveries of the politicians to the banks.

His purpose is therapeutic. A man at play with the freedoms of his mind, believing that it is allegiance to the truth and not the flag that rescues the citizens of a democracy from the prisons of their selfishness and greed, Twain aims to blow away with a blast of laughter the pestilent hospitality tents of a society making itself sick with its consumption of “sweet-smelling, sugar-coated lies.” He offers in their stead the reviving wine of the dear lamented past, and his autobiography stands, as does his presence in this book, as the story of an observant pilgrim heaving the weighted lead of his comprehensive and comprehending memory into the flow and stream of time.

Excerpted from "Mark Twain’s America" by Harry Katz and the Library of Congress. Published in October 2014 by Little, Brown and Company. Copyright © 2014 by Harry Katz and the Library of Congress. All rights reserved.

Shares