Yesterday, the Republican Party did what pretty much everyone free of financial incentive to spin expected: It won a bunch of close races in mostly red states and, as a result, reclaimed its position as the majority party in the United States Senate. There are votes still left to be counted and the outcome of Louisiana's December runoff may change the final numbers a bit, but the bottom line is that for the first time since 2006, the U.S. Congress will be run in both chambers by the GOP.

So this is a good day if you're a Republican, probably the best once since Nov. 3 of 2010. But once the confetti is swept up and the champagne bottles are recycled thrown away — once the task before them is not to bash the president and motivate their voters, but to make some of the unpleasant choices that come with being in the majority — Republicans may find their internal squabbling, so prominent during last year's government shutdown but papered over for much of this year's campaign, back with a vengeance.

At the very least, that's what the American Enterprise Institute's Norm Ornstein, the center-left pundit, longtime Washington fixture and co-author of "It's Even Worse Than It Looks: How the American Constitutional System Collided With the New Politics of Extremism," told Salon in a recent interview. Rather than being the end of the party's years in the wilderness, Ornstein says, the GOP in power may find that its problems have only just begun. Our conversation is below and has been edited for clarity and length.

Now that Republicans have won back the Senate, what lessons (if any) do you think they’re going to take away from the 2014 election?

I think they're going to say [their strategy] worked. The problem that they have is, saying it worked means basically saying: Obstruct what Obama wants, delegitimize him — that's a formula for victory. And a good portion of the base is going to say, "See? We won without having to do anything on immigration, without having to do anything to reach out to minorities, single women, young people, the growth areas in the electorate. We just keep on doing what we've been doing and we're going to be in great shape."

Right. Even before results started coming in yesterday, Erick Erickson was already laying the groundwork to argue that GOP leadership will need to prove to the Tea Party base that it deserved their support.

You're going to have plenty of establishment figures who view it the other way, but they're going to be minority voices.

With the obstruct/delegitimate approach having been vindicated, is there any reason to expect, as some have, that Republican control over the entire Congress will lead to significantly more cooperation with the president and less gridlock?

No. There isn’t.

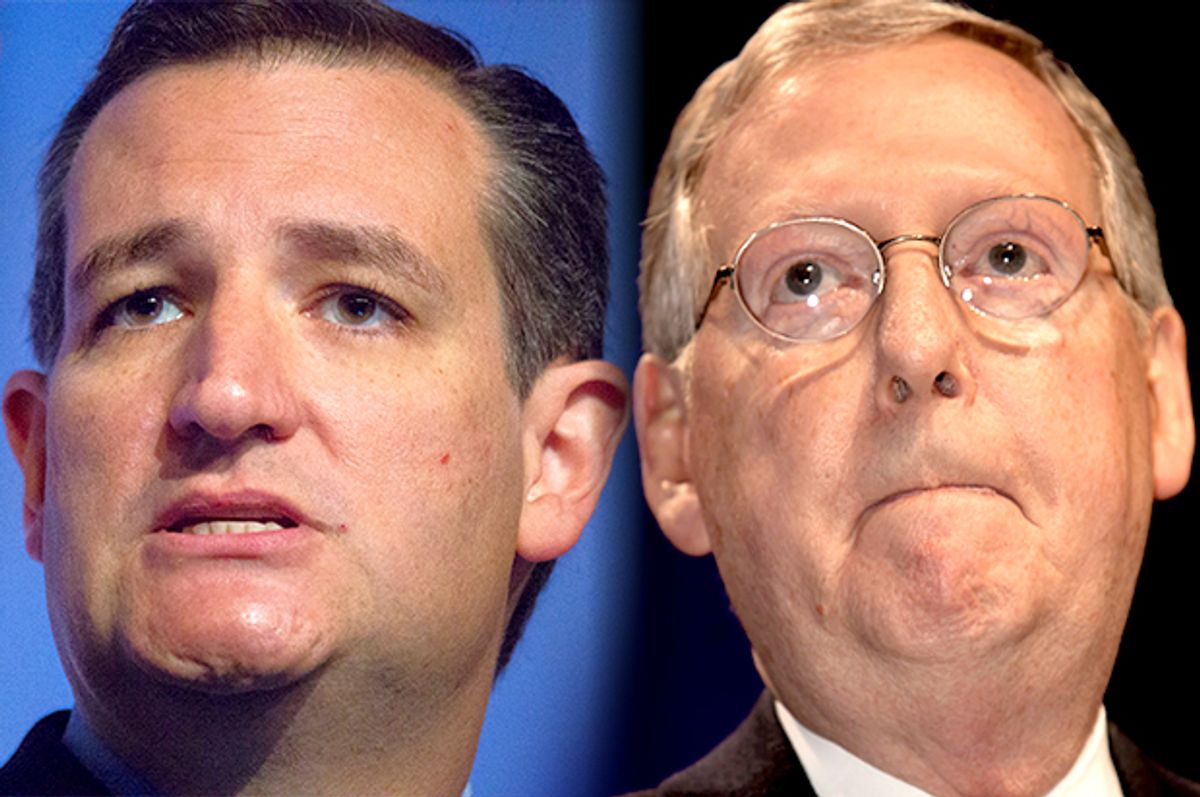

If you look at the piece that I wrote last week, about what happens with a Republican Senate, you can see that the story here is a Republican Party still facing almost an existential battle between — well, there are no moderates anymore, but between an establishment and more pragmatic wing that believes that if you want to compete for the White House, you've got to show a positive agenda and show that you can govern, do some things that work with Obama; and a more radical wing that is reflected by what Ted Cruz said to the Washington Post just a couple of days ago, that now's the time to flex our right-wing muscles.

My first thought when I saw that interview and Cruz’s comments was, “Great. We get to do late 2013 all over again.”

Yeah. I think you can find some areas where you'll actually see some policy made, but where you have to start is, What are the areas where Republicans, generally, and their allies on the outside agree and the issue is not of great concern for the insurgent radicals?

So, trade's a good example. Most Republicans are for trade; you’ve got some isolationist libertarian protectionist types who aren't, but they're very much a minority. A signing ceremony on trade with Obama doesn't inflame [the base], and business likes it, and it's an area where Democrats are divided. So, sure, do trade. Same with sentencing reform: Satisfy your libertarian base (most of the rest of the GOP’s radicals don't really care about that all that much). You can do NSA reform for the same reasons — and you could look at NSA reform as a way to embarrass or criticize Obama and also divide Democrats.

But you get much beyond that, and you're going to have problems.

And that would suggest to me that hopes (or fears) of returning to the grand bargain are pie-in-the-sky.

Pie-in-the-sky would be a generous way of putting it, yes.

First of all, a grand bargain is going to have to involve revenues, and for a GOP base that tastes blood after a victory, the idea that the party would then backtrack would just drive them nuts. At the same time, you do hear a lot of Republicans on the trail talking about the need for entitlement reform. With the possible exception at one point of Mike McFadden in Minnesota, who said that he would be open to raising the Medicare age, any time [Republican candidates] were pressed to get more specific, they just danced completely away from it.

And that’s because a grand bargain, in the end, is going to involve making changes in Medicare and Social Security that will likely, when you're actually talking in concrete terms about doing them, really tick off a good portion of the Tea Party base, the older base that thinks we should slash government — but not those programs.

Last but not least, there’s the issue of what could happen if there’s a Supreme Court vacancy sometime in the next two years. When the Democrats used the so-called nuclear option, Republicans vowed they’d enact vengeance once they were in the majority. Is there reason to worry that that could manifest itself in them breaking the norms around Supreme Court justices and blocking a mainstream nominee?

Yes, but I think you have to say it depends on the context. When in the next two years? And which vacancy?

If it's a Ruth Bader Ginsberg vacancy, where you're not changing the fundamental balance of 5-4 [conservative vs. liberal], then I think you would see plenty of Republican pushback if Obama tried to nominate a liberal, and basically a signal from Republicans in the Senate, "We'll confirm somebody, but it's got to be a moderate.”

But even that depends on whether the vacancy occurs in the next year or close to the 2016 presidential elections. And if it's a vacancy that involves one of the conservative members of the court, then I think you would see Republicans absolutely to the mat to keep Obama from picking anybody that would change that balance from its current one, which is so favorable to them.

Shares