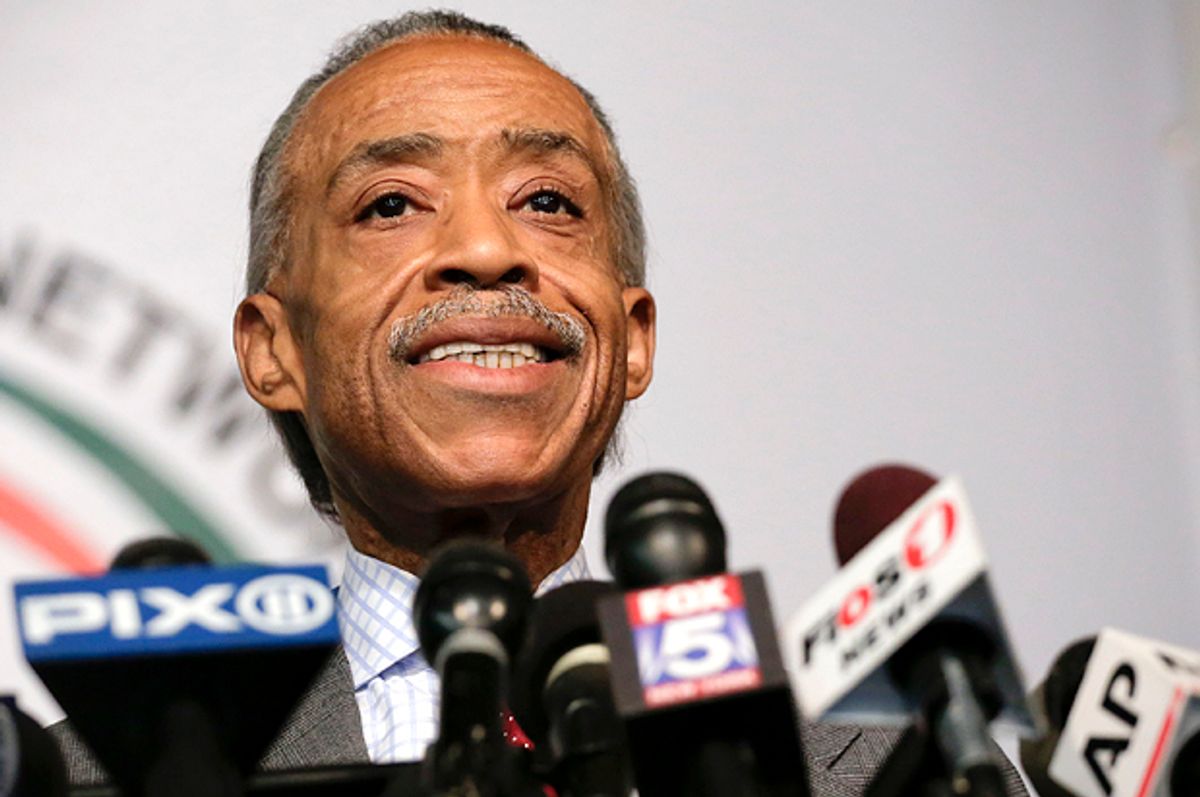

Once again, the Rev. Al Sharpton has been receiving sloppy wet kisses from prominent politicians and other power brokers; once again, as the New York Times reported on Wednesday, he’s been enjoying something like immunity from “the sorts of obligation most people see as inevitable, like taxes, rent, and other bills.”

The news that Sharpton and his for-profit businesses are in arrears to the feds and New York state to the tune of $4.5 million (give or take a million, if you believe his latest prevarications) is nothing but an old, familiar twist on his perennial boast --most recently at his 60th-birthday party-cum-fundraiser for his so-called National Action Network -- that, “I’ve been able to reach from the streets to the suites.”

What he's really been able to do, for as long as I've known and loved him, is to affirm that "society is basically a hustle from top to bottom," as he put it to me in 1992 for a profile in the New Yorker.

At the recent fundraiser, an aide to President Obama read a message praising Sharpton’s “dedication to the righteous cause of perfecting our union,” and New York “Mayor Bill de Blasio and Gov. Andrew Cuomo hailed him as a civil rights icon,” as Times reporter Russ Buettner noted.

Two decades ago, New York Gov. Mario Cuomo and New York Mayor David Dinkins were doing much the same. When George Pataki defeated Cuomo in 1994, Sharpton was one of the first people the new governor received in his Albany mansion after taking office. “He plays them like a piano board,” former Mayor Ed Koch told me then, as I was riding around with Rev. Al from church pulpit, to street demonstration, to dinners at Junior’s and Le Petit Auberge, to his former homes in Queens’ Hollis neighborhood and Brooklyn’s East Flatbush.

Sharpton was playing me, too, but not for accolades. I profiled him a second time, for the New Republic, in 1996, and for Salon, in 2002, when he was considering running for president, as he did in 2004.

I was drawn to him again and again not only because he was inexhaustibly fascinating or at least useful to power brokers, penitential white liberals, and editors and readers but because he’d come to embody the vast tragedy of black central Brooklyn. "Embody” and "vast" fit him perfectly then. And he leavened what he embodied with an absurd but nearly redeeming humor and roguish charm.

Having packed the pews at Mt. Ollie Baptist Church in East New York one autumn Sunday in 1992 with mostly older black men and women who’d flocked to hear him preach, Sharpton at one point dropped his regal, admonitory posture to offer this aside: “Now, I know, that some of you do say, ‘Oh Lord, the [bad] things I used to do, I ain’t gonna do no more.”

Stage pause.

“The things you used to do, you cain’t do no more!”

That impish recognition of guilt and compassion for weakness had them rolling in the aisles. I learned to detect the same sensibility even in his cold calculation that “society is a hustle from top to bottom.” That doesn’t exonerate him, but it does have the effect of implicating the rest of us.

Where is it coming from? When Sharpton was young, his father had been a successful businessman, raising his family in an imposing home in the leafy Hollis neighborhood. As we stood outside that house in 1992, Sharpton decided to confide in me, for the first time to any writer, that in 1964 his father had impregnated his stepdaughter, who soon presented 10-year-old Al with a brother and a nephew in one birth, prompting his father’s departure and the family’s plunge into near-poverty.

He told me how his brother/nephew, then 28 and living in Alabama, was “in and out of jail, and I identify with him, because he went through some of the same trials I did.” That suggested something about Sharpton’s primal unease and about how he has deployed it.

The New Yorker couldn’t publish what he told me without confirmation from his father, who wouldn’t return our calls. Sharpton promised us proof, either by coaxing his dad or by producing other records, but he never delivered. I kept his early family story to myself. It was Sharpton who revealed it three years later, in his autobiography, "Go and Tell Pharoah."

“I had to watch my mother, whom I loved more than anyone, live with the fact that her daughter had stolen her husband, and that the two of them had given life of a child, out of wedlock,” he wrote. “To this day,” Sharpton added in the book, “I don’t know how [my mother] lived with the humiliation.”

But wasn’t he compounding the humiliation by telling the world, with his quiet, faithful mom still very much alive? Surely he compounded it when he justified his impresario’s role in the Tawana Brawley abduction/rape hoax, writing that at some point Brawley’s case “stopped being Tawana, and started being me defending my mother and all the black women no one would fight for. I was not going to run away from her like my father had run away from my mother.”

It’s hard to see how he helped his mother or any black women in America by slandering an assistant district attorney (whom Brawley, Sharpton and others accused of raping her) and by abusing the criminal justice system and eviscerating the possibility of honest racial dialogue. But Brawley’s own stepfather was abusive; she may well have concocted her rape story to escape him.

You’d have to be a stone not to understand why Sharpton found Brawley’s story compelling and rushed to her aid. But you’d have to be a fool to trust him as a public tribune for letting his passions drive his judgment. No one can build a movement for justice on lies, grandiose distortions, vilification of innocent parties, intimidation of those who may have legitimate differences of opinion, and dehumanization of your political adversaries. (Sharpton was found guilty of defamation and was ordered to pay the slandered $65,000 in the Brawley case, which he did only when Percy Sutton and other black leaders paid it for him.)

The problem with Sharpton’s putative leadership, and the root of his serial dodging of tax burdens and other prosaic public obligations, is that he’s all about tapping vast reservoirs of white guilt and black rage, staging catharses that have become a civic equivalent of the dry heaves. The variety and complexity of black life glimpsed at the Mt. Ollie Baptist Church get lost in the clouds of melodrama that Sharpton draws around himself.

The saddest little secret in his stagy reproaches — one I learned in the months I spent with him and have seen confirmed often since — is that Al Sharpton craves certain white people’s acceptance. He’s more than willing to let us off the hook after making us wriggle just enough to relieve our consciences. He offers reconciliation through ritual rebukes and special exemptions he only half-deserves. He understands this game’s allure and the futility. But until his craving for reconciliation on his terms is satisfied, as it never will be, he’ll always find ways to implicate us all in the game.

Some whites play it almost as well as the master. When I was writing about Sharpton as a columnist for the New York Daily News in the mid-1990s, Mortimer Zuckerman, the paper’s publisher, had a meeting with Sharpton that encapsulated a lot of what I’d learned about him.

Sharpton had been out in front of the Daily News for two days with his megaphone and his sad stragglers, chanting about racism, and now it was time for the ritual extortion meeting, at which the beleaguered CEO learns what it will take to get rid of the annoyance. Zuckerman, along with a black News executive assistant and some editors, had a sit-down with Sharpton and other frozen-in-time protesters. More instructive than the substance of the negotiation was the way the meeting ended.

“I’d like to ask that we all hold hands, close our eyes, and pray,” said Sharpton, careening gently into a holy roll. Imagine Mort Zuckerman and eight or 10 others sitting in a circle with Sharpton, hands joined, heads bowed. “Oh Lord,” Sharpton intoned, “we pray that you will help your servant Mortimer Zuckerman to create a more diverse, inclusionary Daily News. Amen.”

“Excuse me, Reverend Sharpton,” Zuckerman said as all present opened their eyes; “I’d like to address a few words to the Lord, too, if I may.” So all held hands and closed eyes again.

“Oh Lord,” Zuckerman prayed, “we ask that you will protect and prosper our honored guests, and that you will help them to understand that, with your guidance, I, as the proprietor of the Daily News, I will do with it what I think best. Amen.”

As they opened their eyes again, Sharpton raised an eyebrow at Zuckerman and, with a mischievous, connoisseur’s smile, stage-whispered, “Nice!”

I can condemn him for many things, but not for that. And part of me can’t help but forgive him for doing things that pretty soon he'll discover that he “cain’t do no more.”

Shares