Wednesday afternoon, President Obama continued his Post-Election IDGAF Tour by announcing that the United States and Cuba had agreed to a prisoner swap, and will work toward normalizing diplomatic relations between the two countries. The U.S. hasn’t had anything resembling a “normal” relationship with Cuba since the early 1960s, what with all the communism and nuclear missiles and repression of human rights. What the U.S. also hasn’t had in that time is a successful Cuba policy – namely, one that will dislodge the Castro regime and make the place less of an impoverished nightmare.

Instead of achieving its stated goals, our Cuba policy of trade embargoes and diplomatic isolation has instead made poverty in the country even worse, made the United States a target of international criticism, and provided the Castro regime with a handy propaganda tool. The American people oppose the Cuba embargo, more and more politicians oppose the embargo, and the reasons for keeping it in place have long since been discredited. But we can’t seem to move past it, thanks to the political leaders who refuse to move past the decades of sclerotic thinking that was enshrined by awful policy decisions made decades ago.

The outrage at Obama’s announcement was bipartisan, though it came primarily from Republicans. Sen. Bob Menendez, Democrat of New Jersey, said the prisoner exchange “invites dictatorial and rogue regimes to use Americans serving overseas as bargaining chips.” Marco Rubio said that “appeasing the Castro brothers will only cause other tyrants from Caracas to Tehran to Pyongyang to see that they can take advantage of President Obama’s naiveté during his final two years in office.”

Jeb Bush, who this week announced that he’s officially considering running for president, slammed the move as “the latest foreign policy misstep by this president.” Just a few weeks ago, Jeb argued that maybe we should beef up economic sanctions against Cuba and strengthen the embargo “to put pressure on the Cuban regime.”

John Boehner said that the very notion of discussion of normalized relations with Cuba should be off the table until such time as the Cuban people live in freedom:

[embedtweet id="545280744499986432"]

The implied (or in Jeb’s case: explicit) message in all these critiques is that the current Cuba policy of embargo and isolation – which has stood since the height of the Cold War in 1961 – should continue. After five decades of zero major policy changes and zero progress toward the stated objective of freeing Cuba from the Castros, our political class is issuing a bold call to give things a bit more time. Just like in Iraq, real results from our Cuba policy have always been just around the corner, except that predictions of the Castro regime’s imminent collapse stretch back decades.

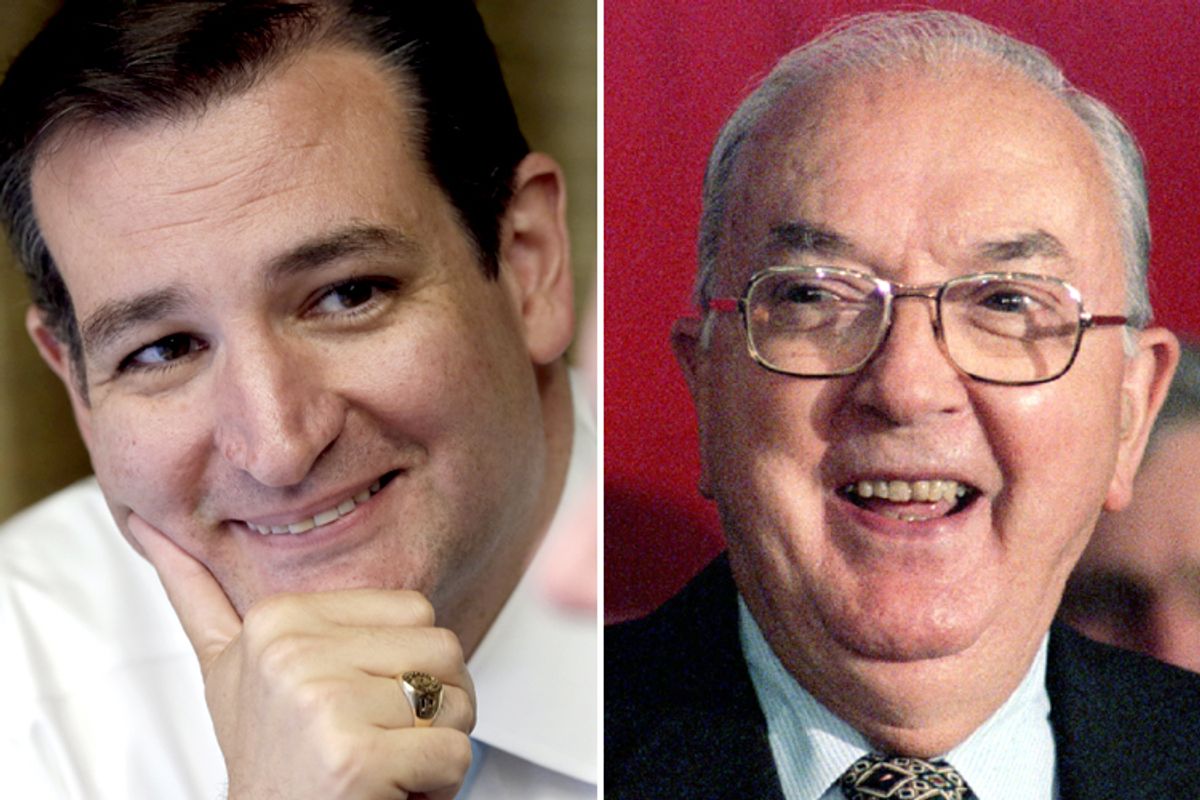

Let’s go all the way back to February 1996 and the crisis that established our useless Cuba policy as law. Throughout 1995, the newly empowered Republicans in Congress were pressing hard to adopt a more aggressive posture toward Cuba. Led by Sen. Jesse Helms and Rep. Dan Burton, members of both parties rallied behind the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act, which bumped up sanctions against Cuba and prohibited any form of U.S. assistance until such time as a democratically elected government was in power in Havana. “If anything, with the collapse of the U.S.S.R. – and the end of Soviet subsidies to Cuba – the embargo is finally having the effect on Castro that has been intended all along,” Helms said in February 1995. “Why should the United States let up the pressure now? It’s time to tighten the screws – not loosen them.”

The Clinton administration resisted, arguing that the legislation encroached on the executive branch’s authority to conduct foreign policy. But the White House buckled in February 1996 after the Cubans shot down two civilian aircraft piloted by Cuban-American members of an anti-Castro group called Brothers to the Rescue. The Atlantic published an excellent rundown of what happened: essentially, part of the group’s mission was to intentionally violate Cuban airspace, and they were warned against doing so by both the Cuban and American governments, but disregarded those warnings. The Cuban air force blew two Brothers to the Rescue planes out of the sky without making any attempt to force the planes to turn around or land.

The ensuing crisis played right into the hands of the hard-liners, who amended the Cuban Liberty and Democratic Solidarity Act so that the Cuban embargo – which had been imposed through a series of executive orders – would be codified as part of U.S. law and no longer subject to the discretion of the president. Clinton, who had previously objected to precisely this sort of encroachment on executive authority, signed the bill into law without objection. Following the law’s passage, its supporters confidently predicted the end of the Castro regime. “He's on the ropes,” Burton said of Castro. “I think this is the last nail in his coffin.” Helms was also bullish: “Farewell, Fidel.”

They were, of course, wrong. And not only were they wrong, they also made it all but impossible to undo the embargo, which to that point had done nothing but fail, and which has continued to do nothing but fail. And in a weird way, for some people the persistence of the embargo in spite of its utter ineffectiveness has become a justification in and of itself for maintaining it – we’ve been doing it for this long, why stop now? Here’s Elliott Abrams in the Weekly Standard arguing that our Cuba policy should be maintained simply because it’s been maintained for decades:

The American collapse with respect to Cuba will have repercussions in the Middle East and elsewhere—in Asia, for the nations facing a rising China, and in Europe, for those near Putin’s newly aggressive Russia. What are American guarantees and promises worth if a fifty-year-old policy followed by Democrats like Johnson, Carter, and Clinton can be discarded overnight? In more than a few chanceries the question that will be asked as this year ends is “who is next to find that America is today more interested in propitiating its enemies than in protecting its allies?”

To state that argument is to refute it: How can anyone trust that America will follow through on a policy when we’ve been sticking to the same unchanged policy for 50 years in the absence of any evidence of success? Seems like we’ve demonstrated our commitment. The better question is why we should put any trust in the people who keep trying to convince us that a Cuba policy borrowed from the Kennedy administration will succeed if only we give it just a little more time.

Shares