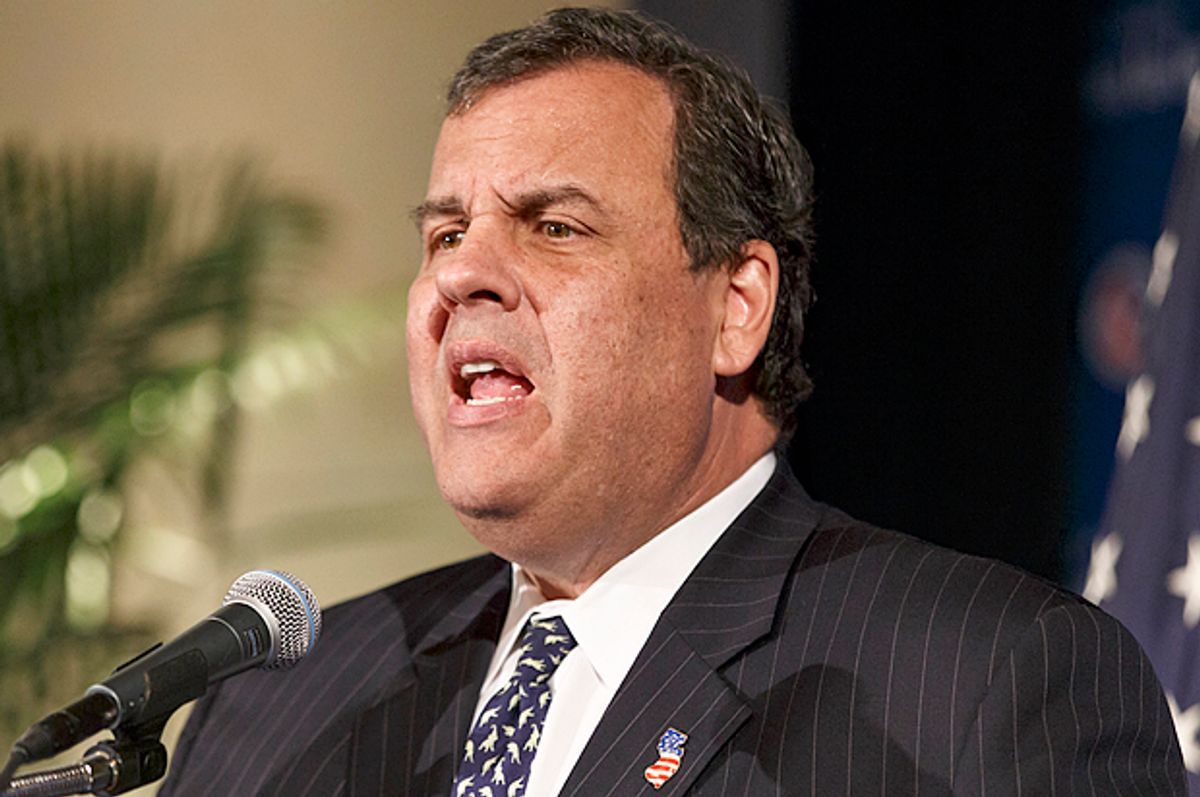

New Jersey Governor Chris Christie is getting a heaping of well-deserved grief for his comment, in an interview with the New York Times, that parents “need to have some measure of choice” about whether or not to vaccinate their children. And the clarifications he provided later didn't do much to help his case. The fact of the matter is that measles, once eradicated in the U.S., is back -- and it's thanks to the ill-advised "choices" of a few that the disease is able to threaten many.

Just how nonsensical is the idea of "choice" when it comes to vaccinations? For that, I defer to this "opinion" piece from the Onion, titled, brilliantly, "I Don't Vaccinate My Child Because It's My Right To Decide What Eliminated Diseases Come Roaring Back."

The joke here plays on the concept of herd immunity: when enough people in a community are vaccinated against a disease, the entire population -- including those too young or immunocompromised to receive the vaccine -- is protected, because the virus is no longer able to find enough hosts through which to sustain itself. The more transmissible an infection, the higher the level of herd immunity needs to be to keep it at bay. And measles is one of the most transmissible infectious diseases: in an unprotected population, one infected person can pass the disease on to anywhere between 12 to 18 people. That's known as its basic reproductive number, or R0. The R0 for Ebola, in comparison, is 2.

In an immunized population, of course, measles' R0 drops from 18 to something closer to zero. To get it there, there's a minimum percentage of people who need to have received the MMR vaccine: it's somewhere between 90 and 95 percent, according to Stephen Morse, a professor of clinical epidemiology at Columbia University’s Mailman School of Public Health.

Nationally, MMR vaccination rates are good, if not great: the U.S. government's target for maintaining herd immunity is 90 percent, and in 2013, 91.9 percent of children aged 19 to 35 months received at least one dose of the vaccine, according to CDC data. But MMR coverage in 17 states fell below the 90 percent threshold, dropping as low as 86 percent in some states. Furthermore, even among children who were vaccinated, one in 12 didn't receive their first dose on time. Aside from potentially making the vaccine itself riskier, that also leaves a wider window during which not-yet-vaccinated children are left vulnerable to the disease.

A Christie spokesperson, in attempting to clarify the governor's statements later on Monday, made the not-so-clear point that "different states require different degrees of vaccination" -- he appears to be arguing that individual state governments should be able to decide which vaccines to mandate, and that in so doing, they should attempt to "balance" the perceived risks and benefits of vaccination (more on that below). It's true that states differ on when, and how often, children need to receive the MMR vaccine, but it's probably not a coincidence that the states with the strictest requirements for vaccinations -- Mississippi and West Virginia don't let parents claim religious or personal belief exemptions -- also have high MMR vaccination rates for school-aged children (in Mississippi's case, the highest), and have been measles-free for the past decade.

Even state-by-state statistics aren't necessarily telling, however -- the CDC points out that pockets of anti-vaxxers where outbreaks are most likely to occur can be found even in states with generally high vaccination rates. Research suggests that people who refuse to vaccinate for personal reasons tend to cluster together; even individual private schools with loose vaccination requirements may create the conditions necessary for disease transmission.

As Christie later acknowledged, his argument that “not every vaccine is created equal, and not every disease type is as great a public health threat as others" definitely couldn't be used to justify opting out of the measles vaccine. The MMR vaccine is widely understood to be safe; the study linking it to autism thoroughly debunked. Measles, on the other hand, kills, and can lead to nasty complications. In fact, Morse told Salon, it's the misconception that measles isn't a big public health threat that's likely led people to underestimate the urgency of receiving the vaccine -- and thus, ironically enough, to the disease's resurgence.

"People have recalibrated their thinking about the risk of measles," Morse explained. "And it is very potentially a very serious disease. But if you only have a few people infected, therefore you think your child's chances of getting infected are small." If you believe that what you're protecting against isn't very likely, it can diminish the perceived benefit of the vaccine.

What past experience seems to have shown, Morse added, is that measles is out there. "If we stop immunizing, once introduced, it's my opinion that it will find fertile ground among people who have not been immunized and have not yet been infected," he said. "The bottom line is we'll suddenly see much more cases coming back, and people will begin to realize that measles is not gone. And then they'll probably start wanting their children to be immunized again."

And the same holds, Morse said, for what Christie might call "lesser" diseases. If they truly weren't a problem, after all, it's unlikely that we would have developed vaccines for them in the first place. "That's partly political and economic," Morse said, "but truthfully, the reason why certain vaccines exist is because there was a push and a desire to make them." Plenty of diseases we immunize against -- chickenpox, even the flu, for example -- wouldn't kill most of us. But when the proportion of people receiving vaccines is so much higher than the proportion contracting the disease we're immunizing against, we, in keeping, become more aware of the vaccines' risks. It almost makes sense -- until it doesn't.

Shares