White House press secretary Josh Earnest wasn’t just being diplomatic or clever yesterday when he said he feels sad and sorry for Rudy Giuliani, the former “America’s mayor” who’s been raging like a sidewalk lunatic at President Obama. There actually is something sad about Rudy’s long self-destruction, which began before his disastrous presidential primary bid of 2008. Sad, but possibly instructive to the future sidewalk lunatics among today’s Republican presidential wannabes. Maybe you had to be with Giuliani at the start of his electoral career to learn what they and the rest of us should learn from this spectacle: not to gloat or cluck our tongues, but to consider how often genuine political promise coexists with puerility and worse.

Throughout the fall 1993 New York mayoral campaign, I tried harder than any other commentator I know of to convince my left-liberal friends that Giuliani would win -- and that he probably should, because Democrats had all but asked for it.

In my New York Daily News column, in the New Republic, and on cable and network TV, I insisted it had come to this because racial “Rainbow” and welfare-state politics were imploding, not just in New York and not only thanks to racists, Ronald Reagan or robber barons, but because something had gone wrong with liberal politics itself. You didn’t have to believe all of Giuliani’s “colorblind,” “law-and-order,” free-market rhetoric to want some big shifts in liberal Democratic paradigms and to see that, in New York City, some of those shifts would require a political battering ram, not a scalpel.

I spent a lot of time with Giuliani during the 1993 campaign and during his first year in City Hall, and while I criticized him several times for presuming far too much, I defended a lot of his record to the end of his tenure, and still would defend some of it. He forced New York, that great capital of “root cause” answers to every social problem, to get real about remedies that worked, in the world that we had to work with. Some of these remedies turned out to be preconditions for progress of any kind: I saw Al Sharpton blink as I reminded him in a debate that twice as many New Yorkers had been felled by police bullets during David Dinkins’ four-year mayoralty, which preceded Giuliani’s, than during Giuliani’s then-seven years in office (1994-2001).

Even as late as July 2001, when Giuliani’s personal and political blunders were beginning to eclipse his accomplishments and he had only a lame duck’s six months to go, I showed in a New York Observer column that he’d facilitated housing, entrepreneurial and employment gains for people whose loudest advocates called him a racist reactionary. James Chapin, the late democratic socialist savant, considered Giuliani a “progressive conservative” like Teddy Roosevelt, who’d been a New York City police commissioner before he’d been president.

Yet, even after 9/11 had given Chapin’s comparison real resonance, Giuliani couldn't have carried his methods and motives to the White House without damaging the country, for two reasons that run deeper in him – and probably also in Chris Christie, Scott Walker, Ted Cruz, Rick Perry and other wannabes -- than “horse race” liabilities like a loss of one’s temper at a podium.

The first serious problem facing politicians like this is structural and political: A man who fought the inherent limits of his mayoral office as fanatically as Giuliani would have construed his presidential prerogatives so broadly that he’d have made George W. Bush’s notions of “unitary” executive power – and, yes, some of Barack Obama’s notions along those lines -- seem soft.

Even in the 1980s, as an assistant attorney general in the Reagan Justice Department and then as U.S. attorney in New York, Giuliani was imperious and overreaching. He "perp-walked" Wall Streeters out of their offices in dramatic prosecutions that failed. He made the troubled daughter of a state judge testify against her mother and against the former Miss America Bess Myerson in another failed prosecution charging that Myerson had hired the daughter to bribe her mother the judge into helping “expedite” a messy divorce. The jury was so put off by Giuliani’s tactics that it acquitted all concerned.

At least, as U.S. attorney, Giuliani served at the pleasure of the president and had to defer to federal judges, as of course he did also as mayor. Had he become president, however, U.S. attorneys would have served at his pleasure -- a dangerous arrangement in the wrong hands, as we learned when Alberto Gonzalez was George W. Bush’s A.G.

As mayor, Giuliani fielded his closest aides like a fast and sometimes brutal hockey team, micro-managing and bludgeoning city agencies and even agencies that weren’t his, like the Metropolitan Transportation Authority and Board of Education. They often deserved it richly enough to make his bravado thrilling and effective. But Rudy Savonarola wasn’t above cutting indefensible deals with crony contractors and pandering shamelessly to some Hispanics, orthodox and neoconservative Jews, and other favored constituencies.

Even the credit that he claimed for transportation, housing and safety improvements belonged partly to Dinkins’ and other predecessors’ decisions and to economic good luck: When Giuliani left office the New York Times noted that on his first day as mayor in 1994, the Dow Jones had stood at 3754.09, while on his last day, Dec. 31, 2001, it opened at 10,136.99: “For most of his tenure, the city’s treasury gushed with revenues generated by Wall Street.” Dinkins, in contrast, had had to struggle through the aftereffects of the huge crash of 1987.

Ironically, it was Rudy’s most heroic moments as mayor that spotlighted his deepest liabilities. Fred Siegel, author of the Giuliani-touting "Prince of the City," posed the problem in 2007 when he wondered why, after Giuliani’s landslide 1997 mayoral reelection (when a lot of liberals and even a few lefties voted for him), and with the city buoyed by new safety and economic success, Rudy couldn't “turn his Churchillian political personality down a few notches."

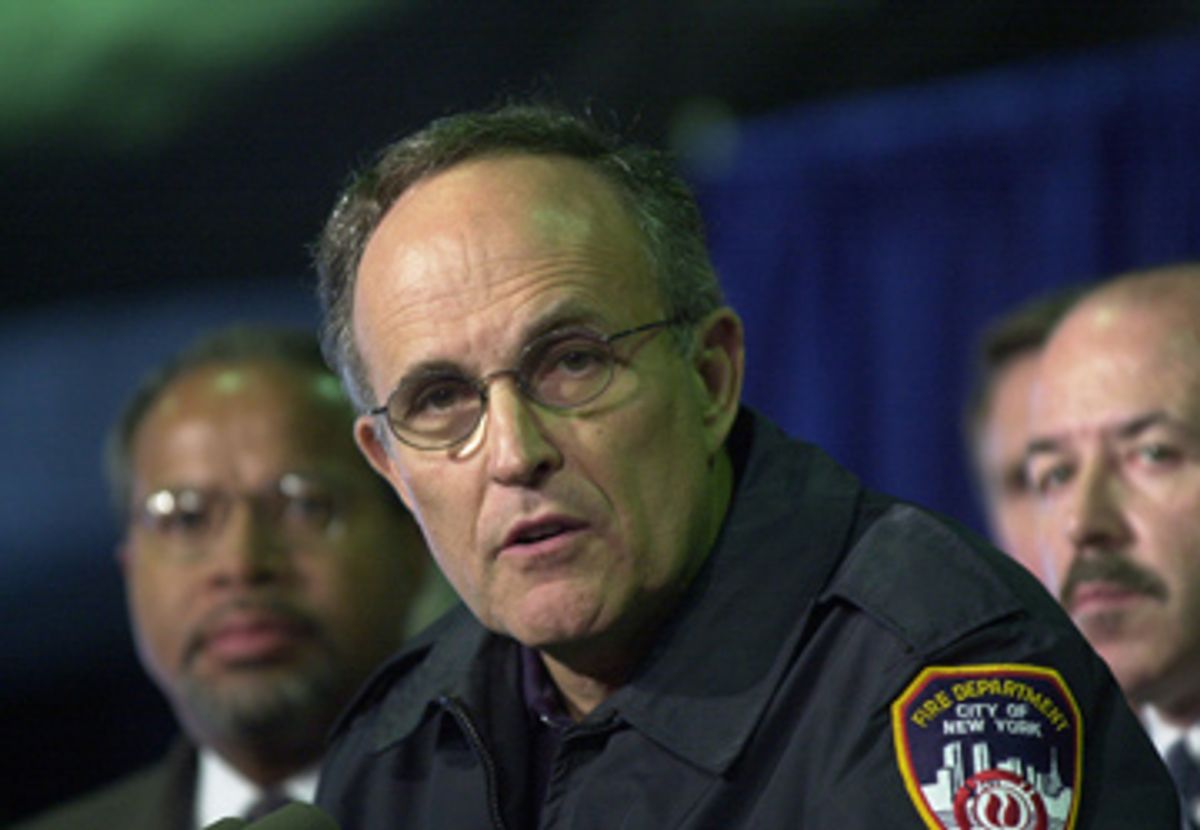

I’ll tell you why: Giuliani’s performance was sublime on 9/11 for the unnerving reason that he’d been rehearsing for it all his adult life and had remained trapped in that stage role. When his oldest friend and deputy mayor Peter Powers told me in 1994 that 16-year-old Rudy had started an opera club at Bishop Loughlin High School in Brooklyn, I didn’t have to connect too many dots I was seeing to notice that at times he acts like an opera fanatic who is living in a libretto as much as in the real world.

In private, the Giuliani I knew in the mid-1990s would contemplate the human comedy with a Machiavellian prince’s supple wit. But whenever he walked out onstage, he tensed up so much that even though he could strike credibly modulated, lawyerly poses, his efforts to lighten up seemed labored, like the rigid, creepy smile that popped up even as he railed at Obama. What really drove a lot of this, then as now, was a zealot’s graceless division of everyone into friend or foe and snarling, sometimes histrionic, vilifications of the foes. Those are operatic emotions, beneath the civic dignity of a great city and its chief magistrate.

I knew more than a few New Yorkers who deserved the Rudy treatment. I’m glad that some of them got it. But only on 9/11, when the whole city became as operatic as the inside of Rudy’s mind, was he able to project himself so convincingly as America’s Mayor. For once, his New York rearranged itself into a stage fit for, say, Rossini’s “Le Siege de Corinth” or a dark, nationalist epic by Verdi or Puccini that ends with bodies strewn all over and the tragic but noble hero grieving for his devastated people and foretelling a new dawn.

It's unseemly to call New York's 9/11 agonies "operatic," but it was Giuliani who called the Metropolitan Opera only a few days after 9/11 and insisted its performances resume. At the start of one of them, the orchestra struck up a few familiar chords as the curtain rose on the entire cast and Met stagehands, administrators, secretaries, custodians. And standing up there among them was Rudy Giuliani, bringing the capacity audience to its feet to sing “The Star Spangled Banner” with unprecedented ardor. All gave the mayor what the New Yorker's Alex Ross called "an ovation worthy of Caruso." A few days later, Giuliani proposed that his term be extended on an “emergency” basis beyond its lawful end on Jan. 1, 2002. It wasn’t, and the city did as well as it could have, anyway.

If this country had suffered another devastating attack before the 2008 primaries were over, Giuliani’s presidential prospects might have soared beyond recalling. But the constitutional notion of recall would have soared beyond recall right along with them.

Even a stopped clock is right twice a day, and Giuliani was right for the 15 minutes when his municipal stage was a national one as never before. But we didn’t have to make him president to learn why even a grateful Britain dumped Churchill the first chance it got after V-E day: While there are times when liberal democrats do have to take up arms to defend liberal democracy itself, they should be wary of people who live for those times. That’s the lesson in Rudy Giuliani’s self-destruction, and, yes, it’s sad and complicated.

Shares