Countless journalists have proclaimed, often after a few rounds at the local watering hole, that someday they’ll finally get around to writing that novel. The mythical offspring that’s been gestating for an indeterminate period down in their guts that will be about more than just fishing or dirty cops or their quirky childhood or whatever—it will be, at its pulsating core, about the American Dream. Or it would be if they didn’t have so many deadlines and bills.

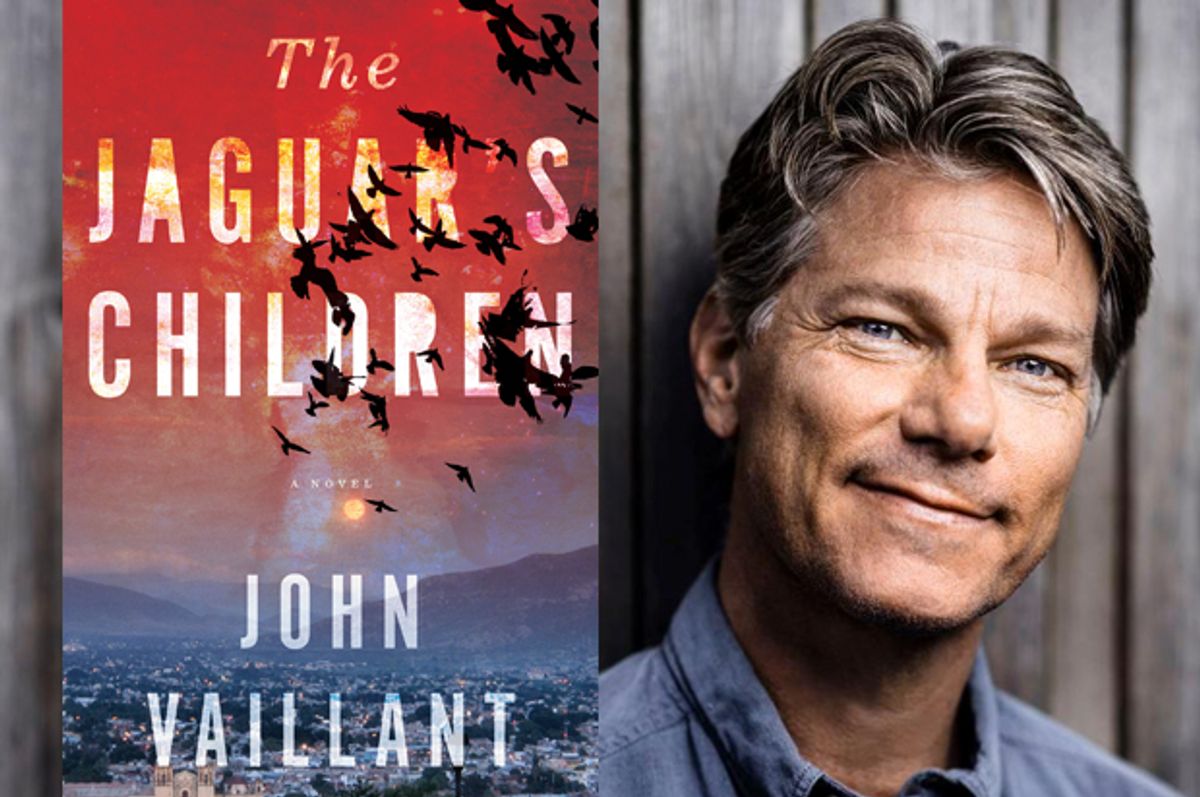

After a decade and a half in journalism that culminated with two award-winning nonfiction books, John Vaillant has actually done it. The twist on his debut novel, however, is that the protagonist chasing the American Dream is stuck inside a truck that immigrant-smuggling “coyotes” have abandoned in the Arizona desert. “The Jaguar’s Children” unfolds through a young immigrant named Héctor’s flashbacks to his boyhood in the rural hills of southern Mexico up through his decision to leave Oaxaca for better economic prospects north of the border. As the water and food inside the smuggler’s truck runs out and the other immigrants around him begin to perish, Héctor’s mind unravels as the story of how he ended up there builds to a collision of geopolitical, personal and mythical factors.

This is all quite a departure from Vaillant’s highly acclaimed first two books. “The Golden Spruce” told the story of a mentally ill British Columbian logger with nearly superhuman stamina who converted to environmentalism and then illegally chopped down a sacred, ultra-rare tree as a deeply quixotic act of protest. Valliant's bestselling follow-up, “The Tiger,” focused on the hunt for a man-eating tiger near Russia’s far eastern border with China and North Korea. They are both extremely difficult to put down.

The seed for the “The Jaguar’s Children” was planted nearly a century ago when Vaillant’s grandfather, who studied archaeology in the 1920s at Harvard, went down to Mexico and wrote what stood for two generations as the definitive history of the Aztec nation. Although Vaillant never met his grandfather, he has spent much time near the border and in Oaxaca for the past three decades. I spoke with Vaillant about why his time there led him to switch over to fiction, how he navigated the controversial topics baked into the plot of his debut novel and a few questions that had been gnawing at me about his nonfiction work. Our conversation has been edited for clarity.

Did you feel like you needed to switch from nonfiction to fiction because you would never be able to find a subject more mind-blowingly improbable than the stories you covered in your first two books?

After “The Golden Spruce,” I couldn’t imagine finding another story that combines those different qualities of heavy industry and myth and environment and history and psychology in such an interesting way … and then “The Tiger” came along, and it had that multifaceted fascination. With both of those, I wasn’t looking for stories, they came to me. And fiction is also a kind of visitation.

When “The Jaguar’s Children” came to me, my family and I were living in Oaxaca, in southern Mexico, and I was still working on “The Tiger” and engrossed in it, but I wasn’t looking for another story. The opening lines of the book, “Hello, I’m sorry to bother you,” just came to me out of the ether. I’m a nonfiction person, a journalist, and I tend to get my quotes from verifiable sources. This was a really different kind of experience. But I wrote this line down, and very quickly that opening scene of a young man in deep distress, being trapped somewhere along the border, came out. I wasn’t sure where it was going to go, but I knew I had to pay attention.

There was nothing in Oaxaca that I felt I could write about without it becoming a travel piece or a political human rights piece, and there are a lot of those out there already. I got to go to a writing retreat in 2011 and I realized that fiction was the only container big enough to hold everything that I had seen, learned and felt about the experience of being in Mexico and being related to people who had long and complicated histories with Mexico and experiences I’ve had over the past 30 years on the border. In this case, nonfiction was just too narrow of a framework.

Can you talk about the different challenges and rewards of writing a nonfiction book versus a novel?

They’re challenging in very different ways. One person I know describes nonfiction as building houses and fiction as building boats. It’s an order of magnitude more difficult when you attempt a novel. Coming from nonfiction, I feel like fiction is harder and those nonfiction books were almost like apprenticeships to train me to handle narrative and character.

What’s easier about nonfiction is that you always have the facts to rely on—you just go back to what happened. When you get lost or lose your way, you just go back to the story. You may have to do a lot of sleuthing to flesh out the story, and that’s the thrill—those discoveries. It’s like prospecting for gold. Fiction is kind of the same, but it’s coming out of the ether. They’re both journeys of discovery, but the information is coming from a different place.

The standard I hold myself to is: Can I justify writing fiction if it’s not about important, pressing things that are happening to people now? However, I think it’s kind of a deadly motive to have the agenda lead the story. That’s the best way to wreck everything.

You’re a white, roughly middle-aged man. The protagonist of your story is an impoverished, young campesino from the outskirts of Oaxaca. What drew you to focus on traditions and life in rural Mexico? Was it intimidating to take on a topic so far removed from your own personal experience for your first novel?

Yeah, it was a huge challenge, but that also made it exhilarating. As far as taking on Hector (the protagonist), it hadn’t been my plan until he announced himself to me. There’s an improv rule, “never refuse an offer,” and this was about as clear a gift from the muse as I’ve ever received. It seemed really daunting, like kind of a hazardous undertaking. But I felt confident I could do it, because this voice was so clear in my mind.

I had a good enough sense of what the real, pressing issues are in southern Mexico and the border that I felt I could evoke that accurately. My nonfiction training has made me very cautious… that if I say something, it needs to pass muster with an expert. Before anybody in the outside world saw it, a number of Mexicans read it, people who know Oaxaca intimately.

A friend of mine interviewed [author] Jonathan Dee, and he said “Don’t write what you know, write what you want to know.” That’s my motivating principle, as a writer. I go into places where I’m very out of place and I become a student, but I also try to manufacture a stable platform from which the experts can speak. In this case, I’m working with Hector to get all these stories and concerns out of him. Fiction is a collaborative process, it isn’t just about you. You’re not entirely in control of the process. In that sense, it’s like a guided hallucination.

You mention not wanting your fiction to have an agenda, but his book is very empathetic toward immigrants trying to enter the U.S. from Mexico. You go into the history of how NAFTA destroyed the ability of millions of Mexicans to make a living in their home country. You detail the pain, challenges and risks that they take to get here. You give a voice to a perspective that’s often ignored. Do you see this book as a project of advocacy or even activism?

I’m very confident that I’m representing the experience of people from southern Mexico who can no longer make a living growing and selling corn and are wanting to do something for their families. This is how it is for them. They are coming from a civilization that was built on corn and the strength of their connection to the land. That is being undermined now by outside forces. There’s a saying in Oaxaca, “Without corn, there is no country.” That’s not true for us [North Americans].

I don’t think it’s “activist” to describe the experience of another person, just because it's a hot-button issue. But I do hope if people read this, and then they see some guy mowing their grass or cleaning their pool, they’ll think about what it took for that person to get here … and what would we do in the same situation? It’s kind of an invitation to try on the skin of another person. I think that's one of the reason we read novels, is to get into this other head. In this case, it’s topical and contentious, but that’s our problem. Most people don’t want to leave, they would prefer to stay if they could make it work, economically.

I see “The Jaguar’s Children” as an opportunity to get to know some of these issues from a very different point of view.

Without giving away too much of the plot, the spread of genetically modified crops, specifically transgenic contamination of native plants, is a topic you cover in “The Jaguar’s Children.” What do you think of the current state of the debate over GMOs? Many journalists strive to portray themselves as objective when they cover topics like this for fear that nobody will take them seriously if they voice an opinion. Were you worried, as a journalist, about making one of the more nefarious characters in the novel a representative of major agribusiness corporation?

As a writer, I’m not really that personally interested in GMOs. I’ve read enough to know GMOs aren’t bad, in and of themselves. There are a lot of different ways to modify a plant and to make blanket judgments about that is ignorant. But as I got to know Cesar [a friend of the novel’s protagonist], I realized I had to learn more about GM corn in order to keep up with him. It made me analyze the ethical/spiritual bind he was in working for the biotech industry.

There’s even a part in the book where he talks about how the Zapotec people modified corn and it modified us, through selective breeding over millennia until you got these big, fat kernels. It took several thousand years to get us to the corn we’re familiar with now. But what I wanted to explore is if your whole identity is based on the corn that you and your ancestors have grown—which is something that’s really hard for people who have been disconnected from the land to understand—the blurred lines between yourself and the things that you grow and the land it comes out of. The milpa is their mother.

So what would it mean if you built a civilization, and pyramids, and an alphabet, and corn helped you do that… and there’s now the possibility of you being beholden to a foreign corporation simply to procure the next season’s viable seed? The challenge to your sovereignty, your identity, your whole concept of what life is… the stakes are very high. In Oaxaca and Chiapas, people are truly fighting for their lives and their livelihoods and corn is the battlefield.

Your previous book, “The Tiger,” was a bestseller that focused on an endangered subspecies of tigers native to a remote region of Russia’s far east where they are in grave danger of being poached into extinction. Has all the attention from your book had any impact on efforts to protect the Amur tiger? How have things changed in that region since the book was released back in 2011?

A lot of people have been working on that portfolio very, very hard. I think the biggest change has been relations with China. There is still a massive, and very destructive demand for animal parts. China and Vietnam are these black holes in which endangered species disappear, never to be seen again. However, a lot of volunteer work has been done on the Chinese side to remove the snares and there are these “tiger days” now where people have these festivals celebrating the tiger. So I think there’s a local awareness and pride that’s being rekindled… but it's very, very tenuous. I remain hopeful. It’s kind of the same issue with us and climate change. We have this awareness, but can your behavior catch up quick enough?

I have to ask one question about “The Golden Spruce”: What do you think are the odds that Grant Hadwin is still alive. And—if you think there’s even a remote chance, what do you think he would be doing now?

I’ve thought about that a lot and I don’t think there’s a chance. The people who knew him best are the ones who seem to think he’s still alive. This guy was a father and unless he’s completely insane—and insane people don’t last that long in the wilderness... I think Hadwin’s madness was episodic and exacerbated by stress. So if he got away and wrecked his kayak and lived on this island and came down, I think he’d reconnect and want to be with the people who mattered to him.

I have a hunch that he drowned and I would bet a lot of money on that. But if he happened to pop up in a remote mining town in British Columbia, I’d say, “I’ll be damned,” but I wouldn’t be totally shocked. He had a lot of superhuman qualities, he did a lot of things that should have killed him.

Shares