“There will never be a nigger in SAE!” chanted a bunch of Biebers from the dark side. The OU frat video released earlier this week shocked the nation. But not me. I never believed the lie of a post-racial America, so new heights of white shittiness don’t surprise me. Instead, my mind went to that kid who still longed to be the unwanted “nigger” in a fraternity where he’d be like Baldwin’s “fly in the buttermilk.” That black boy or girl who has no idea who the hell s/he is, who thinks that finding a home in places like the SAE house might offer some desperately needed sense of belonging. I write this in the hopes of reaching that lost black body floating adrift in the chaos of racial identity — just like I did for much of my life.

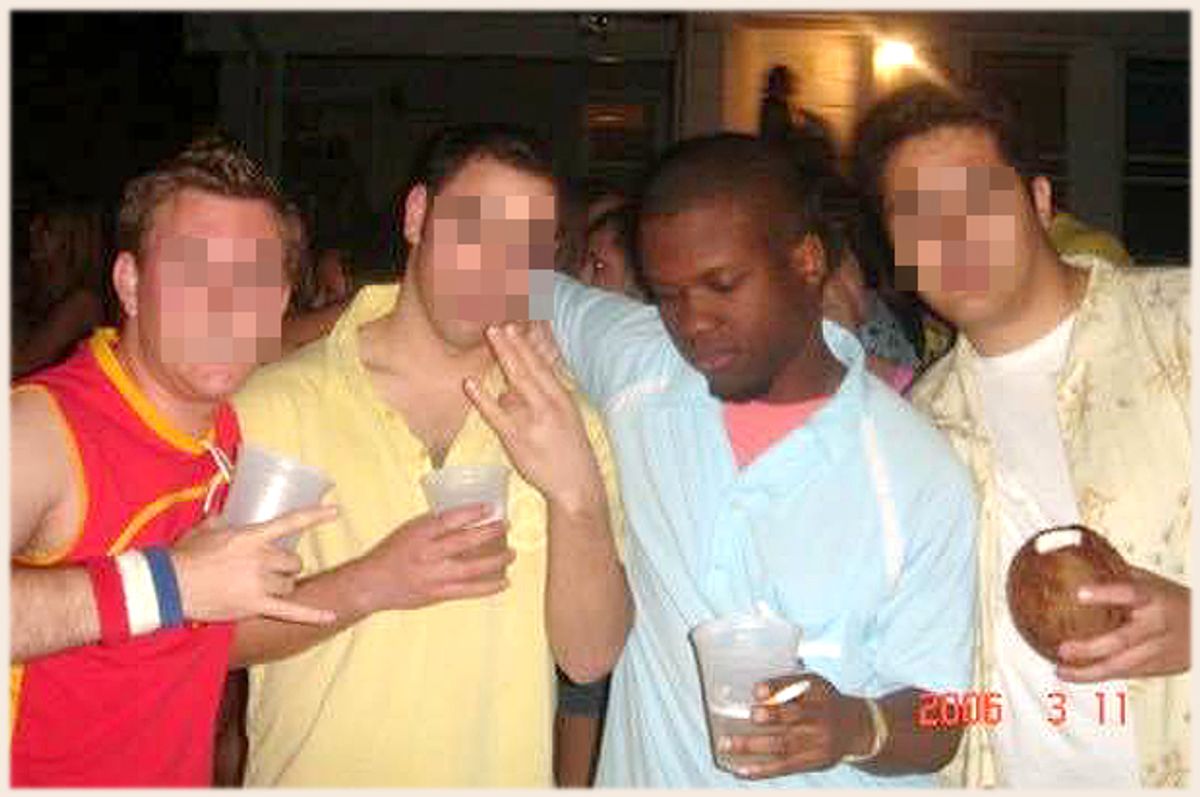

In the fall of 2003, I pledged a fraternity, the only chocolate member in the whole house. White kids trying to be black don’t count, of course. I was a blackout drunk, and I resolved long before setting foot on campus to surround myself with other blackouts, even if they were all white. Never mind that I was the first in my family to go to a proper university. Academia was the last thing on my mind. Fraternity culture gave me a place where I could indulge the way I wanted, without loved ones or teachers or longtime friends to slow me down. During orientation, I asked which houses hazed the worst and drank the hardest. It was nothing short of a drunk’s providence that landed me at 3 Frat Row.

In the house I settled on, the hazing was mental from the jump. Older guys seeking to humiliate me and 10 other strangers laughed when, after being told in a “lineup” to actually “Fuck the wall like I meant it!,” I asked said wall if “she” enjoyed my black cock. It was a stupid bit of levity in an otherwise out-of-control 10-week hazing process. (My hell week ended with someone losing the top half of a finger. The chapter has since been shut down.) I took a bleak sort of pride in making the house’s worst hazer laugh so hard he had to leave the room, but I couldn’t see my shucking and jiving for what it was. I signed up willingly for the puking and the push-ups and the fists through panes of glass and the destruction of property and the coke-fueled misery that led to my half-assed suicide attempt and the being shitty to women and all the clichés of being a “frat dawg.”

When I passed the old group photos hung in the frat house, I would scan previous chapters for other chocolate faces. There was one from '96-'97. Another from '81-'82. Whooooaaa. One from 2000-'01. That was recent! “They’re probably all proud Republicans,” I couldn’t help but think.

At the time, I saw nothing wrong with this environment. During pledging, there was a frat brother who’d make me sing country music at dinner; no way the house colored boy would be into country, he probably wagered. Clearly, he didn’t know how white my childhood surroundings had been. In school settings, at least.

I came up in a decidedly middle-class, entirely black neighborhood in Baltimore. My mother was a government employee who worked impossibly hard, as black mothers with hardheaded black children often do. My father was a Vietnam vet who quit his warehouse job upon the birth of my younger sister to become Mr. Mom to both of us. My parents went to great lengths to assure that I received the best education the city could offer and a shot at opportunities they never got. My first and only year of public school was overcrowded and out of control: A classmate told me to say ahh, then promptly stabbed me in the roof of my mouth with a pencil. My parents’ had seen enough, and worked their magic to get me a shot at testing into the Calvert School, alma mater of John Waters, which I attended until sixth grade.

In my teen years, I went to a private school held up by many as the best in the area, but I quickly learned I wasn’t like the other boys, virtually all white and upper-middle to upper class. I spent those years being reminded of my blackness, mostly in negative ways. This alienation — coupled with static from black friends in my neighborhood for “acting white” — properly knocked my racial identity off its axis. Attempts to thrive simultaneously in both the black world at home and the white world at school soon gave way to a misguided quest for assimilation into the latter. I fried my scalp with relaxer to straighten my hair. I lusted after white female classmates, while denying that anything black could be beautiful. My father had hit me before, out of the frustration and pain of losing my older half-brother to violence and seeing me repeat his mistakes. But he didn’t touch me when I told him that black girls were ignorant and ugly. I will always remember the disappointment and heartbreak etched into his face that night.

Years after my private-school stint, my mother would ask why I didn’t tell her how I was treated at school. I mean, yadda yadda yadda, “snitches get stitches,” I’d rationalize to myself. But I also didn’t want to visit any more hurt and stress on a strong black woman who’d already sacrificed plenty. I still hear echoes of my father’s reminders that in this white man’s world, I had to be at least twice as good as my white counterparts. This was the real affirmative action. Affirm yourself, your black skin and your big lips and your big nose and your hair, even at its nappiest. Fucking love that shit, because they don’t feel obligated to. And take action, even when you don’t feel like it, even when it’s the unpopular move, because to regress is to die.

I’d gotten the the memo outside of home as well. I just never opened the envelope. “You can fuck ‘em, but you can’t be ‘em,” warned a concerned black coach who’d noticed my group of friends’ attempts to “be” white. We could dye our hair blond and date white girls and listen to Smashing Pumpkins, but we were still black as all hell. I thought he was being harsh, but I can see now it was a message of self-love and self-acceptance I simply wasn’t ready for.

It didn’t take long for me to learn where I stood in this environment of prestige and tradition — “a diverse community of racist white people,” as one older classmate put it to me. On an overcast September day at recess, one of my first few days in this school, I was called nigger to my face for the first time. All I did to provoke this was introduce myself in an attempt to make a new friend.

And while I wanted nothing more than to put my fist through the back of that kid’s skull, I receded in the face of this ugliness in what would be the beginning of a pattern of turning more cheeks than I probably should have. Even as a pubescent little shit, I knew I had what Toni Morrison referred to in a 1998 interview with Charlie Rose as a “moral high ground” in the face of these not-so-microaggressions. Yet, it was hard to see the tactical advantage, as these classmates of mine, reflections of the bigots in their homes, like all those spiritually sick individuals suffering from the diseases of racism and prejudice, felt they occupied that high ground as well, the delirium of white supremacy making them believe their own bullshit. It took some time and some sobriety to get in touch with gratitude for attending these schools, but at the time, I wanted nothing more than to get the hell away.

I held a naive notion that college would be different. But wherever I went, there I was. During the two-month period of pledging, it seemed like that long sought-after feeling of being “a part of” was within my grasp. But it was soon after that an older brother mentioned, in an “I don’t care how this makes you feel” way that one is afforded by the cashmere womb of white privilege, that the reason people didn’t fuck with me during that time was because I was black and no one wanted to be known as the “racist house.” I was crestfallen; I’d thought it was because they really liked me. This house, racist? No! Never mind that my pledge brother had been called a “spic” in front of 100 people at a tailgate weeks before.

When asked why I didn’t go Omega or Alpha, prestigious black fraternities known by my family and neighbors, I used the excuse that black frats were kind of a joke at my school, disorganized and sparsely populated. Yet I wouldn’t have joined them even if they were legit. The insanity and idiocy of (white) Greek life was the only normal I knew then, and the next logical step in a life of seeking white approval. Admittedly, being a lone black face in a patently white space had been my default setting throughout most of my life.

Today, I want to go back and tell my younger, frustrated, confused self that it’s going to be all right. That I’m enough. “Don’t let these Lacoste-wearing motherfuckers get you down. Your black features are beautiful. Your heritage is fucking awesome!” The self-doubt of my formative years can still creep up on my ass, and I can still feel burdened with the daunting task of “Keeping It 100" (read: keeping it real). But most of my life I’ve either kept it 17 or kept it 1000 while trying to color within the lines.

Today, I seek that middle ground, that lofty state of being: “Yourself.” All of that noise in my head — from the committee that led me through those frat house doors telling me I belonged there to the insanity of trying to spike my hair like Pauly D — stemmed from a virulent self-loathing that I’ve thankfully surmounted in the years since. It’s taken me damn near 30 years, but I’m finally learning that what other people think of me is none of my damn business and that chasing white approval, even as a means of survival, is a fool’s errand indeed.

If I’m honest with myself, there’s still work to be done, and I still find myself struggling to find equilibrium occasionally. When even the most well-meaning friend/co-worker/girlfriend throws the “You’re the whitest guy I know” at me, it’s like Nat Turner’s ghost taps me on the shoulder and says, “Just do it.” And conversely, whether it’s at the barbershop or at a cookout, I still get the “You ain’t a real nigga ” look/line/whatever. (Was it my skinny jeans that gave it away?) I want to ask: If I walked up in Barney’s, would I not get followed, scoped out, harangued, even after droppin’ hard, legally earned stacks, only to be stopped and frisked once out on Madison Ave., cuz I should know better, right?

I like what I like, and I am who I am, But most important, I can look myself in the mirror today. In essence, I’m connecting to my own sort of black privilege. For me, that privilege is a silver lining resiliency, a mental toughness whose bedrock was laid down centuries ago by ancestors who lived more hell in 24 hours than I will in a lifetime. Through the cascading pain and injustice dealt us, and through all the shit we’ve put ourselves through worshiping false idols in innumerate forms and complexions, we have built a spiritual fortitude that can be tapped into not only to survive, but to thrive. I strive for an unshakeable pride in myself, one that must be rediscovered on a daily basis most times.

Eventually, I had to come to grips with my drunken lifestyle and start living as a sober man. So too did my blackness require a rehabilitation. All of it’s been a process not without some pain, but it’s brought me to a point where I will never be anyone’s “nigger,” in SAE or anywhere else.

Shares