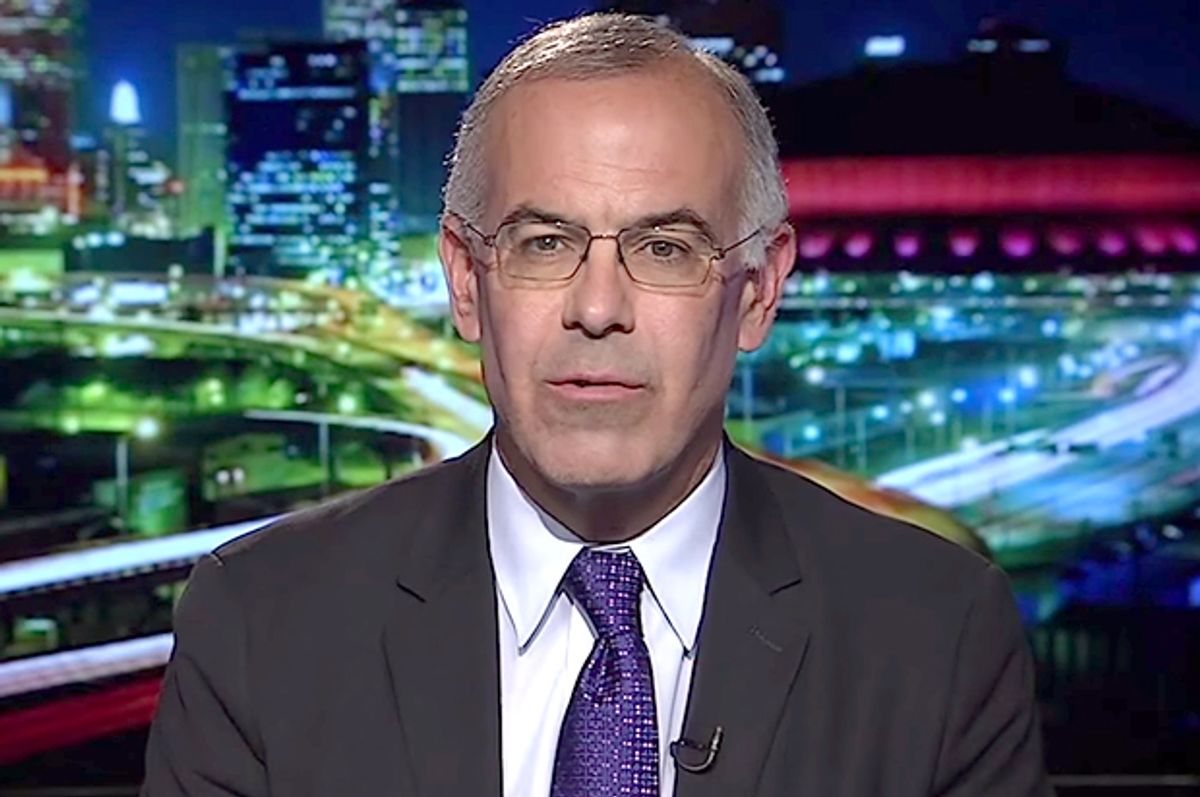

Because he no longer has any influence on the Republican Party, and because it’s quite obviously been years since he spent more than 40 minutes on a column, I try not to write about David Brooks too much. But because I am an imperfect person who lives in a fallen world, and because Brooks is still one of the most popular columnists at one of the globe’s most important newspapers, I sometimes fail. And as soon as I finished reading Brooks’ latest piece — an execrable collage of half-assed ruminations on anti-Semitism, which is supposedly different (and worse) than other forms of hatred — I knew that today would be one of those times. So, with apologies to all those who believe deeply in the virtue of self-restraint, let’s begin.

As is suggested by its oddly utilitarian headline, Brooks’ new column, “How to Fight Anti-Semitism,” is intended to offer guidance to a world increasing roiled by hatred of Jewish people. According to Brooks, there are “three major strains of anti-Semitism circulating” throughout the world right now, and he’s got wisdom needed to take ‘em down, one-by-one. The problem, though, is that Brooks’ solutions are far from innovative or revelatory. And while it’s not necessary for every columnist to reinvent the wheel, it’s clear by the end of his piece that he’s not even trying to find new answers because, in truth, he only believes in one: violence.

Before he implicitly argues that death is the only solution, however, Brooks offers a quick recap of anti-Semitism today. Unfortunately, he appears to know about as much about it as someone who browsed through a copy of the Atlantic while waiting to see his shrink. He’s right, of course, when he notes that anti-Semitism is rampant throughout the Middle East. And the fact that anti-Jewish conspiracy theories are popular with the region’s privileged elite and its oppressed masses should not be forgotten. But when Brooks writes that anti-Semitism in the Middle East “cannot be reasoned away” and “can only be confronted with deterrence and force,” he comes dangerously close to endorsing the same Manichaean worldview of the Iranian regime.

When Brooks relies on a flawed piece from the Atlantic’s Jeffrey Goldberg to support the idea that Jewish people may have to flee Europe, though, he’s just being lazy. The Continent’s doubtlessly seen a rise of anti-Jewish violence and abuse; frankly, given the de facto depression that’s smothered the eurozone since 2008, that’s what a student of history would expect. But if it’s as bad to be a Jewish person in Europe right now as Brooks thinks, then how could “marches, sit-ins and protests,” as Brooks recommends, be enough? When Brooks says that nonviolent resistance has worked in the past against bigotry, he’s only telling half of the story. Because those actions were ultimately an attempt to change the law; they weren’t merely intended as persuasion.

Inevitably, Brooks next comes to the problem of anti-Zionism on college campuses, which, of course, he conflates with Jew-hatred. His thoughts on this overhyped new topic of elite conversation are even more half-baked than his ones about the Middle East and Europe. When he blames millennial opposition to the Israeli occupation on “hav[ing] been raised in a climate of moral relativism,” he demolishes whatever was left of the barrier separating repetitiveness and self-parody. When he implies that the kids today are misguided for thinking Israel’s “cruel and colonial policies in the West Bank” have something to do with its unflattering global image, I wonder if he’s using scare-quotes, or if he thinks that’s a fair price to pay for ignoring Gaza entirely.

Mediocre and superficial as all this may be, Brooks saves his worst for last. This is where the piece’s pro-war subtext comes closest to the surface. The folks in the Obama administration, Brooks complains, “know that the Iranians are anti-Semitic, but … put this mental derangement on a distant shelf.” Stemming from their desire to avoid yet another major conflict with a majority-Muslim country, these officials, Brooks says, “negotiate … as if anti-Semitism was some odd quirk” when it’s really “a core element” of the “mental architecture” of Iran’s leadership. That’s likely true; but doesn’t the U.S. negotiate and partner with many people who hold odious views?

Yes, Brooks says, but that doesn’t matter because anti-Semitism is different. According to Brooks, bigotry, which he distinguishes from anti-Semitism, “is an assertion of inferiority and speaks the language of oppression.” But anti-Semitism, on the other hand, “is an assertion of impurity and speaks the language of extermination.” The “logical endpoint” of anti-Semitism, Brooks writes, “is violence.” For the women killed by Elliot Rodger; the trans* people regularly murdered with impunity; the countless African-Americans who died due to slavery, Jim Crow and police brutality; and the young Muslims murdered recently by an Islamophobic fanatic in Chapel Hill, this is, apparently, not the case.

To be fair, there’s a robust, ongoing and lengthy debate within learned circles about anti-Semitism and other forms of hatred. There are people of good faith who strongly believe that the two are separate phenomena, with the former spanning millennia and the latter being the product of the contemporary age. I count myself as strongly in the camp of those who see all people as fundamentally the same, their hatreds and evil included. But, in the end, to even begin to have that bigger, better conversation is to give Brooks too much credit. He’s not trying to understand human nature; he’s just doing what he always does, pushing for some people to kill other people somewhere far, far away.

Shares