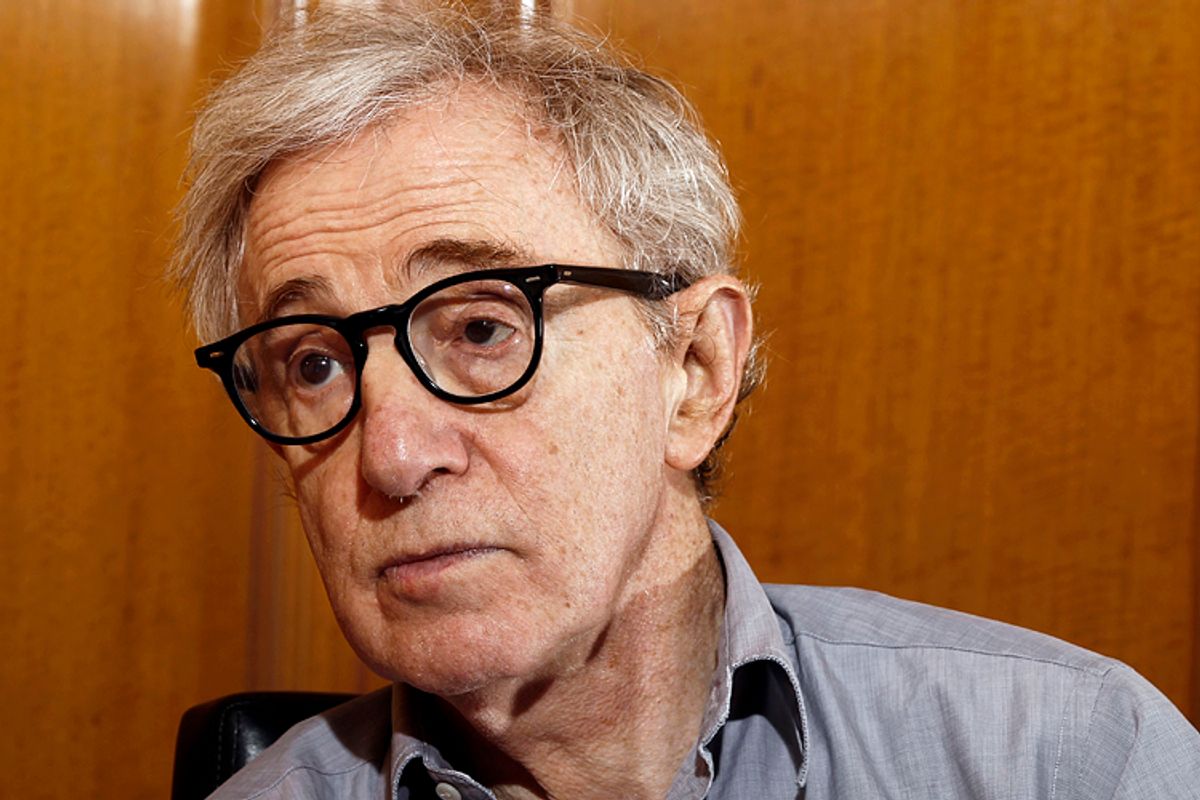

When Mariel Hemingway was 18, Woody Allen chartered a plane to her parents’ home in Idaho because he wanted to take her to Paris. The pair had recently finished working together on “Manhattan,” a film in which Allen stars as a man in his mid-40s who dates Hemingway’s character, a 17-year-old high school girl. (Allen also wrote and directed the film.)

“Our relationship was platonic, but I started to see that he had a kind of crush on me, though I dismissed it as the kind of thing that seemed to happen any time middle-aged men got around young women,” writes Hemingway in her forthcoming memoir.

She warned her parents “that I didn’t know what the arrangement was going to be, that I wasn’t sure if I was even going to have my own room,” though she says they still lightly encouraged her to agree to the trip.

That night, with Allen asleep in a guest room, Hemingway says she woke up “with the certain knowledge that I was an idiot. No one was going to get their own room. His plan, such as it was, involved being with me.”

She didn’t wait until morning to decline his offer. He returned to New York the next day.

In an essay on why Hemingway’s memoir matters, my colleague Erin Keane writes:

When our flawed hero’s fictional character is a thinly-veiled version of his true self, as Allen’s Isaac appears to be in “Manhattan,” the empathy gymnastics even begin to feel absurd — are we conflating what we know about Allen the person with Isaac, a constructed fictional character, just because they look like the same person? For those of us who were taught to be drawn to these ambiguities, to embrace to them, even, the fictional veil of “Isaac” was just enough of a separation between fact and fictional truth to allow “Manhattan” and, by extension, Allen himself, a pure artistic life.

Hemingway’s memoir destroys that separation once and for all. Woody Allen was Isaac, and quite possibly still is.

It’s a nuanced piece asking what it means -- and if it’s even possible in light of allegations that he sexually abused his 7-year-old adopted daughter -- to separate Allen's art from the artist as the edges seem increasingly blurred. The mask is not the face, but his work has always invited audiences to speculate about the boundaries of fiction and autobiography.

When it comes to "Manhattan," Hemingway’s revelation about Allen may seem like life imitating art, but the reality is that the film was, at least in part, art imitating life.

When Allen was 42, he dated Stacy Nelkin, a 17-year-old high school student whom he met after she was an extra in “Annie Hall.” (Nelkin remains a friend and supporter of Allen.)

With "Manhattan," was Allen daring the viewer to judge him, to scorn him as a predator or celebrate him as sexually liberated? Is an exchange about child molestation in “Honeymoon Hotel” a dark joke from a man who assaulted his child, or an artist's use of taboo and gallows humor? Do we see Allen’s guilt -- and catharsis through art -- in Judah confessing to his crimes as though they were a movie plot in "Crimes and Misdemeanors"? ("People carry awful deeds around with them. What do you expect him to do, turn himself in? This is reality. In reality, we rationalize. We deny or we couldn't go on living," he explains.)

Do these things take on meanings beyond the work because of all that we do and do not know?

“Woody Allen is a genius. Woody Allen is a predator,” Keane writes. “He put those two sides of himself together, hand in hand, and dared us to applaud. And we did — over and over.”

But rather than destroying the separation between art and artist once and for all, Hemingway’s memoir may just serve as just another tear in Allen’s thin artistic veil.

Shares