To judge only by appearances, the outpouring of grief by a million-and-a half Singaporeans at the funeral of their country’s founder and longtime prime minister Lee Kuan Yew last week resembles that of Americans at the funeral of Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1945. But, it also mirrors North Koreans’ weeping with unfeigned grief in 2011 over their deceased “Dear Leader” Kim Jong-Il, about whom the less said the better, and of Russians’ in 1953 over the body of Joseph Stalin, who had repelled the Nazi invasion and built a superpower with a safety net but terrorized, imprisoned and murdered millions of innocent people in many countries, including his own.

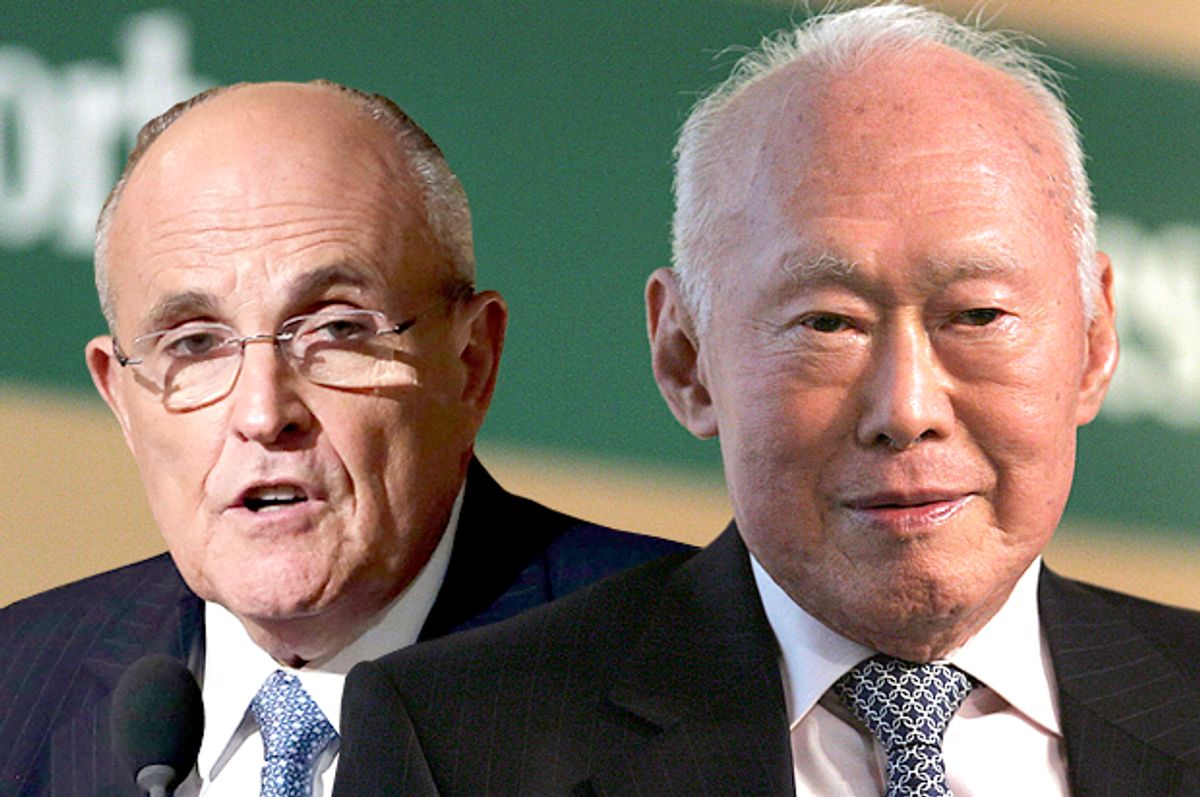

So much for appearances. Lee Kuan Yew was quite a bit more like Stalin than like Roosevelt, but, since Singapore is a tiny city-state and world-capitalist entrepôt, he also resembled New York Mayor Rudy Giuliani, under whom that world city, too, became cleaner, safer, more prosperous – and more sterile, unequal and unjust not only for many of its African-American and Latino-American citizens but also for the one-third of its residents who are poor immigrants and whose lives, like those of one-third of Singapore residents, are glimpsed by most of the rest of us only when we see them at work.

Like Giuliani and Stalin, Lee was clever, disciplined, effective, prescient, racist, vicious, vindictive and a control freak. He cleaned the streets and waterways, selected the shade trees, imposed a somewhat robotic examination-driven meritocracy in education, and secured the comforts of investors, and tourists, and tiny Singapore’s 70,000 resident millionaires (in U.S. dollars) and 15 billionaires by importing more than 1.5 million virtually rights-less migrant workers to keep wages down and instill fear and cultural sterility in generations of Singaporeans:

I am often accused of interfering in the private lives of citizens. Yes, if I did not, had I not done that, we wouldn't be here today. And I say without the slightest remorse, that we wouldn't be here, we would not have made economic progress, if we had not intervened on very personal matters - who your neighbor is, how you live, the noise you make, how you spit, or what language you use. We decide what is right. Never mind what the people think. (The Straits Times, April 20, 1987)

Many ordinary people kissed his feet for that. Welcome to human history and to the downside of human nature.

At least New York’s Giuliani was curbed by state and federal leaders and an independent judiciary, under a Constitution that had been crafted in open debate among brilliant founders. Lee abolished all curbs, and he virtually wrote and interpreted the constitution by himself: “We have to lock up people, without trial, whether they are communists, whether they are language chauvinists, whether they are religious extremists. If you don’t do that, the country would be in ruins,” he said in 1986 while imprisoning and cruelly abusing Catholic Church social-justice workers who were certainly opposed to his practices and whom he also claimed but never proved were Communists.

Like many a silver-tongued, anti-colonialist, anti-racist firebrand who turns his colonial masters’ noble rhetoric against them but winds up employing their tactics against those he’s leading, Lee very tellingly foreshadowed his own transformation from tribune of the oppressed to autocrat of the oppressed during a 1956 debate in the colonial assembly by condemning Singapore’s British oppressors a bit too deliciously:

“Repression, Sir, is a habit that grows,” he taunted Singapore’s British chief minister David Marshall in the island’s colonial legislative assembly. “I am told it is like making love -- it is always easier the second time! The first time there may be pangs of conscience, a sense of guilt. But once embarked on this course with constant repetition you get more and more brazen in the attack. All you have to do is to dissolve organizations and societies and banish and detain the key political workers in these societies. Then miraculously everything is tranquil on the surface. Then an intimidated press and the government-controlled radio together can regularly sing your praises, and slowly and steadily the people are made to forget the evil things that have already been done….”

That is precisely what Lee did as prime minister, as Patrick L. Smith, the former -- and exiled -- bureau chief of the Far Eastern Economic Review, describes unforgettably here in Salon. When Lee and his wife, Kwa Geok Choo, read law at Cambridge, they developed a love-hate relationship to British imperial ways. He even took the English nickname Harry, and, late in the 1960s, when he was becoming Singapore’s strongman, British foreign secretary George Brown told him, “Harry, you’re the finest Englishman east of Suez.”

As if acting out his own prescient taunt to the Brits about the delights of their repression, he used a terrified parliament and judiciary and press to smear, bankrupt, imprison, harass and exile other potential founding fathers. Of J.B. Jeyaretnam, another silver-tongued but more principled member of the opposition in independent Singapore’s first parliament, Lee said: “If you are a troublemaker … it’s our job to politically destroy you. Put it this way. As long as J.B. Jeyaretnam stands for what he stands for – a thoroughly destructive force – we will knock him. Everybody knows that in my bag I have a hatchet, and a very sharp one.”

And, with incredibly petty vindictiveness, Lee’s government pursued Chee Soon Juan, who was fired in 1993 from his teaching job at the National University of Singapore after he had joined an opposition party, and who was repeatedly imprisoned and bankrupted simply for joining an opposition party and for holding small street demonstrations to air criticisms that state-controlled media wouldn’t publish. When Chee, who couldn’t pay his huge bankruptcy penalty, was prohibited from leaving the country to address a human-rights conference in Oslo, Thor Halvorssen, president of the Human Rights Foundation, published an open letter to Lee’s son, Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, noting that "In the last 20 years he has been jailed for more than 130 days on charges including contempt of Parliament, speaking in public without a permit, selling books improperly, and attempting to leave the country without a permit. Today, your government prevents Dr. Chee from leaving Singapore because of his bankrupt status ... It is our considered judgment that having already persecuted, prosecuted, bankrupted and silenced Dr. Chee inside Singapore, you now wish to render him silent beyond your own borders."

Another one-time founding father of Singapore, its former solicitor general Francis Seow, had to flee the country after declaring that its Law Society, which he headed, could comment critically on government legislation. Seow was arrested and detained for 72 days under Singapore’s Internal Security Act on allegations that he had received funds from the United States to enter opposition politics. "[T]he prime minister uses the courts ... to intimidate, bankrupt, or cripple the political opposition. Distinguishing himself in a caseful of legal suits commenced against dissidents and detractors for alleged defamation…, he has won them all," wrote Seow, who, convicted and fined in absentia on a tax evasion charge by Singapore’s courts, lives in exile in Massachusetts, where he has been a fellow at the East Asian Legal Studies Program and the Human Rights Program at Harvard Law School.

It took the undergraduate Yale International Relations Association and the faculty’s Council on Southeast Asia Studies to embarrass Singapore into letting Jeyaretnam’s son, Kenneth, and Chee come to New Haven to speak in 2012. (Seow did not respond to the invitation.)

Lee’s racism was almost quaint, trading on 19th-century notions that his British colonial masters had held: "Now if democracy will not work for the Russians, a white Christian people, can we assume that it will naturally work with Asians?” he asked – not rhetorically – on May 9, 1991, at a symposium sponsored by the large Japanese newspaper Asahi Shimbun.

Race riots among Chinese, Indian and Muslim Malay residents of Singapore in the 1950s had taught him to impose “harmony” through strict allocations of resources and services along race lines: All Singaporeans carry ethnic identity cards.

Lee even invoked genetics to justify his enforced racial harmony and service distribution: “The Bell curve is a fact of life. The blacks on average score 85 per cent on IQ and it is accurate, nothing to do with culture. The whites score on average 100. Asians score more … the Bell curve authors put it at least 10 points higher. These are realities that, if you do not accept, will lead to frustration because you will be spending money on wrong assumptions and the results cannot follow,” he said in 1997, in an interview for the book "Lee Kuan Yew: The Man and His Ideas."

“If I tell Singaporeans – we are all equal regardless of race, language, religion, culture, then they will say, 'Look, I’m doing poorly. You are responsible.' But I can show that from British times, certain groups have always done poorly, in mathematics and in science. But I’m not God, I can’t change you ...” That was in 2002, in the book "Success Stories."

And in 2011, in his book "Hard Truths," we read: "People get educated, the bright ones rise, they marry equally well-educated spouses. The result is their children are smarter than those who are gardeners. Not that all the children of gardeners are duds. Occasionally two grey horses produce a white horse but very few. If you have two white horses, the chances are you breed white horses. It's seldom spoken publicly because those who are NOT white horses say, ‘You're degrading me’. But it’s a fact of life. You get a good mare, you don't want a dud stallion to breed with your good mare. You get a poor foal. Your mental capacity and your EQ and the rest of you, 70 to 80% is genetic. "

Lee dropped his nickname “Harry” while touting his ways against Western criticisms of his mounting offenses against basic freedoms and his -- and China’s -- embrace of top-down, state capitalist control of all society. In 2012 the Economist magazine explained that state capitalism was pioneered by Lee, "a tireless advocate of 'Asian values,' by which he meant a mixture of family values and authoritarianism."

Liberal, it wasn’t. "I had my own run-in with Lee some years ago," former Harvard president Derek Bok told me, "when the government in Singapore jailed the young head of the Harvard Club for 'consorting with the wrong people.' I wrote in protest to Lee and was surprised to receive a letter of several typewritten pages from him trying to persuade me that Asian values are different from those in the United States. Nothing in that experience [with Lee] would tempt me to try to establish a Harvard College in Singapore."

Lee's concoction of "Asian values" was meant partly to deter Westerners from criticizing repressive regimes. And as those regimes try to ride the golden riptides of global finance, communications, labor migration and consumer marketing, they're turning to ancient Confucian, Islamic and even Western colonial traditions to shore up and legitimize their control against huge new inequalities, degrading labor practices and consumer marketing, and criminal behavior.

For a devastating summary of a scholarly work about Lee’s governance that will require 20 minutes and a strong stomach to read, Google “authoritarian rule of law” and “yawning bread,” or go to https://yawningbread.wordpress.com/2013/02/24/book-authoritarian-rule-of-law-by-jothie-rajah/.

“Singapore is improving,” its apologists sometimes insist. But Reporters Without Borders now ranks it an abysmal 151 of 180 nations in press freedoms – down from 135 in 2012. The Economist magazine’s rigorous Democracy Index (pdf) ranks it with Liberia, Palestine and Haiti.

Human Rights Watch calls it “a textbook example of a repressive state.” Two years ago, a five-part Wall Street Journal series documented its abuses of migrant Chinese bus drivers, a paradigm of how it treats the rights-less migrants who are one-third of its population.

(The country’s 2014 Gini coefficient, which measures income inequality, is 0.478, one of the widest in the world.)

Alternative views come only on a few brave websites, such as Online Citizen and TR Emeritus and in the Yale-NUS bubble, which Singapore is taking care to accommodate: When the government tried a few months ago to ban “To Singapore With Love,” a documentary on leftist activists who had fled the country to escape certain imprisonment and worse, Yale-NUS obtained an exemption to show it “for educational purposes” and decided not to use it only after the filmmaker Tan Pin Pin protested that if it couldn’t be shown everywhere in Singapore, it shouldn’t be shown anywhere.

While many Singaporeans are wonderfully astute and fair, owing partly to the very rigor and probity that Lee Kuan Yew demanded, many others are marinating in ressentiment, a curdled bitterness that, unlike clean indignation, blames Singapore’s ills on its critics. The ruling party seems to have hundreds of on-demand trolls who descend upon critical posts, hurling insults, as hundreds did at me when I posted an account of Singapore’s long, close, but secret collaboration with Israel in building up its own military. My Wikipedia page was also altered beyond recognition then by voluntary “editors” whose monikers identified them as Singaporean.

A commenter on another post I’d written questioning Yale’s joint venture in founding a new liberal-arts college with the National University of Singapore exhibited the bitterness: “I don’t see why we need to have a partnership with an institution that has produced the talents who … have morally and financially bankrupted their once great nation,” she wrote. “Call us authoritarian all you want but we are a prudent state while yours is a once great nation that is a banana republic on its way to fascism. And your nation owes us and other authoritarian regimes A LOT of money. All made possible in part by the notables graduates of Yale and other Ivies. I suggest that debt slaves adopt a more courteous attitude toward their creditors instead of name calling and stereotyping. Btw, Feel free to come grovel for a job once this comes to pass.”

A certain hypocrisy is worth noting here. Much of this commenter’s account of what American and global capitalism are doing to republican virtues and prospects is true, but any suggestion that similar things are happening in Singapore generates such excruciating discomfort among its elite apologists that they denounce critics in ways they wouldn’t dare to denounce their own country’s leaders.

As Singapore flourished as a world-capitalist entrepôt, its investors and advisers, including some members of Yale’s governing corporation, paid little attention to the repression and its festering costs. And Lee, in semi-retirement as “Minister Mentor” (his son Lee Hsien Loong is now prime minister and his daughter-in-law Ho Ching is CEO of Temasek, one of Singapore’s two sovereign wealth funds), began sounding wise and avuncular, at least to journalists such as Thomas Plate (writing for Singapore’s government-controlled Straits Times) and Fareed Zakaria (who was a Yale Corporation member at the time).

Like Giuliani and Stalin, Lee certainly had truths to impart to liberals: Because democracy is messy, its public virtues and beliefs do need assiduous cultivation. “You take a poll of any people. What is it they want? The right to write an editorial as you like? They want homes, medicine, jobs, schools,” Lee said in an interview for the 1998 book, "Lee Kuan Yew: The Man and His Ideas." He might have added, rightly enough, that most people even want some authority in their lives. Beyond that, a little island with no natural resources has scant wiggle room. Unlike the sprawling U.S., Singapore certainly has had no blunder room. That makes Lee’s iron grip seem admirable.

But Lee also had many truths to disguise, and, for that, he needed apologists. Thomas Plate, the journalist who became a Distinguished Scholar of Asian and Pacific Studies at Loyola Marymount University and author of the "Giants of Asia" book series, of whom Lee Kuan Yew was the first, assured readers of his long account of the man’s thinking in the Straits Times newspaper that Lee “hated … uninformed debate,” because he preferred “free, frank speech” among leaders who are well-informed and able to debate and govern, over the idea that everyone has a right to speak, no matter how ignorantly or dishonestly.

A veteran Singaporean government manager told me that he considers this distinction “cringe-worthy” because Lee had no use for free, frank speech even among his peers. Remember, he crushed his fellow founding fathers. A Singaporean studying at Yale emailed me that “Tom Plate is too uncritical about a supposed zero-sum game between ‘truth-telling’ and ‘equal’ speech. Liberal democracy believes in the wisdom of crowds, that people refine their political thinking through the act of participating in politics. But the crowds are going to remain dumb if they don't speak. (Funny how dumb has that double meaning).”

It’s not so funny. Elites in the United States and at Davos, unnerved by the Western civic decay that they themselves have caused, are dancing desperately up Singapore’s garden paths seeking elegant reassurance from Lee Kuan Yew’s achievements that ultimately, “the people” can and must be ruled. But global elites can barely rule themselves, and, sooner or later, they’ll grasp the point of the joke about Lee that tells of two dogs swimming in the waters between Singapore and Borneo, but in opposite directions. The dog headed toward Borneo asks the other one why he's swimming to Singapore. The answer: "Ah, the shopping, the housing, the air-conditioning, the health care, the schools. But why are you going to Borneo?" The dog swimming away from Singapore answers: "Oh, I just want to bark."

For dogs, barking is almost as important as breathing; in humans, it means speaking up in ways that nourish the arts and the best political solutions, which emerge from the wisdom of crowds. Without that, a society experiences demoralization, decadence and brain drain. Liberal democracy may be implausible, but it’s indispensable and irrepressible, and, ultimately, it’s the only way to affirm human potential and dignity. Stalin never learned that, and the Soviet Union paid the price. Giuliani hasn’t learned it, but, thanks to constitutional democracy, others have replaced him. Sooner or later, Singapore and China will learn it, too.

Shares