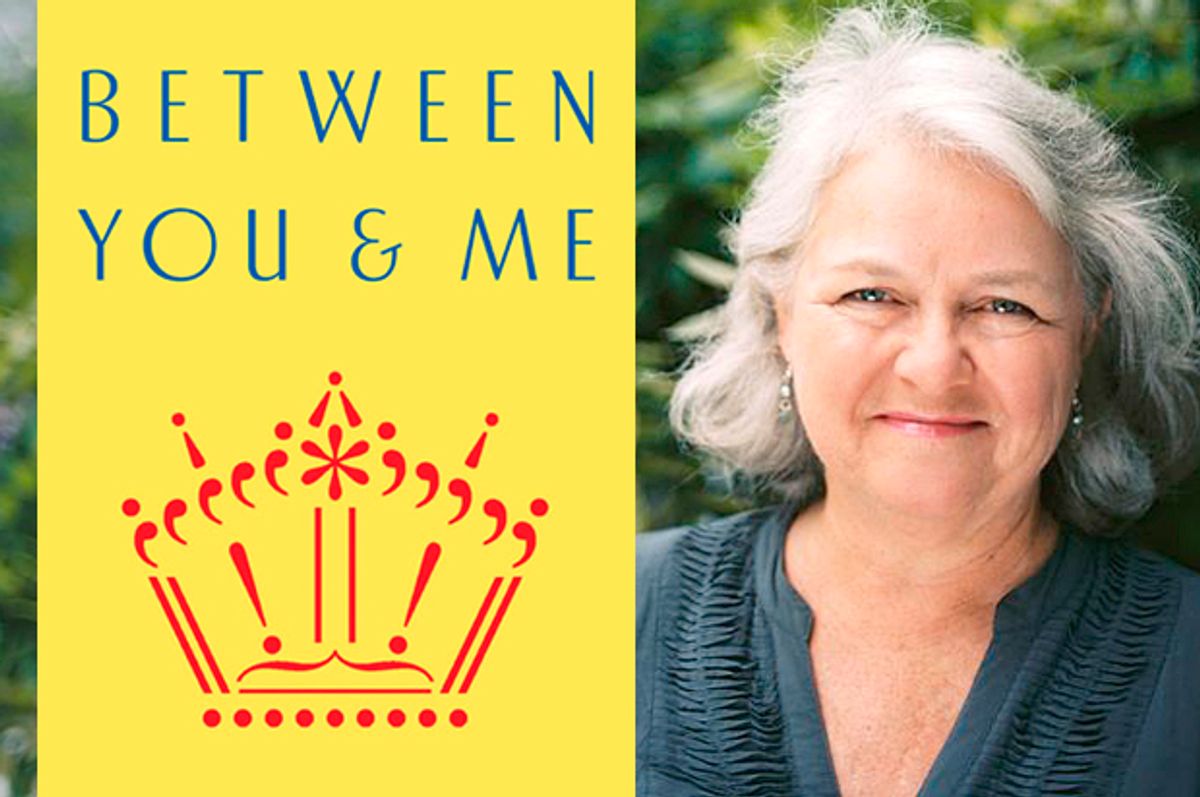

For decades, Mary Norris dreamed of publishing a book, all the while working as a copy editor at the New Yorker, helping make the work of other writers shine. At age 63, she’s finally where she’s long hoped to be with the publication of “Between You and Me: Confessions of a Comma Queen.” Her debut sparkles with passion, warmth, and charm, a collage of memoir, grammar guide, and ode to language, its tools and accoutrements—from the just-so placement of commas to the search for the worthiest pencil. I was thrilled to talk with her, copy editor to copy editor, and she humored me by revealing the inner workings of the New Yorker’s Copy Department. We also spoke about her journey as a writer, editorial hierarchies, and her triumph over envy.

Your job title at the New Yorker is Page OK’er, aka Query Proofreader. What’s your role?

Page OK’er is a job title that I believe is unique to the New Yorker. We query-proofread and also manage a piece through to print. If we see a possible mistake, we’ll flag that. We also will make suggestions for improving the syntax. The writers don’t have to take a suggestion. They might not feel it’s an improvement. If something is correct the way it is, we try not to meddle with it, but if we see some obvious way to make a more compelling sentence, we suggest that.

You started out in doing something like indexing, right?

Yes, I worked in the Editorial Library, where we indexed the magazine. For every cartoon and article and “Talk” story, we would summarize it—even the poems—and file it under author, title, and subject. If people were mentioned in a long fact piece, we would file it under their names. So if somebody wanted to track down a certain article or cartoon, they could just describe it, and we could track it down for them. We were like pre-Google.

Then I went to a department called Collating, another thing of the past. You did not have any personal input; you just transcribed changes from the editor, the author, and the fact checker onto one master galley. But it was a great job because you learned what everybody did while you saw everybody’s changes. And you could see how the piece improved with every revision.

From there, I went to the Copy Desk, working on manuscripts that had been edited. You just did basic things like correcting spellings, but the job was interesting, too, especially because it was under William Shawn, and I got to see his editing. And eventually I became a Page OK’er.

So I just have to know: We New Yorker readers tend to moan about how many issues (or years) behind we are. Do you also have piles of magazines spilling over in your apartment? How far behind are you?

When you work for a magazine, the last thing you want to do when you go home at night is read a magazine, especially if it’s the one you work for. I like to read the pieces that everyone is talking about, especially the ones by my colleagues in the office, and right now I am a few weeks behind. I always look at the cartoons, though.

Being a Page OK’er at the New Yorker must be a job like the mailman used to be; you have to show up, you have to deliver. What happens if you’re ill, or the flu rips through the Copy Department?

Most of the time we manage—we have a pretty deep bench, and it’s good for the younger people to get some experience—but when someone is sick or is on jury duty then others have to rise to the occasion. It is a little bit like being a mailman. Sometimes we get overworked, but we can make up for it when there is a double issue and not much to do the week no magazine is going to press.

Schools are teaching grammar a lot less and relying on technology and word processing programs to “teach” it by default, pointing out grammar mistakes. Do you think this, not to mention texting and tweeting, will have a significant effect on the grammar and spelling of future adults?

That’s not a very nice way to learn, just by having your mistakes pointed out. But there are fun ways to do it: "Schoolhouse Rock," for instance, and pop music. Lately, Weird Al Yankovic has been singing about grammar and usage. Texting and tweeting shouldn’t really affect grammar, though spell-check programs and autocorrect will have an effect on spelling. I believe that the only way to learn English grammar is to study a foreign language.

Your profanity chapter is full of hilarious examples of language writers are competing to get into the magazine. One piece by Ben McGrath debuted “bros before hos” in the New Yorker, creating a spelling dilemma with “hos”—hmm, I see that Webster’s gives the plural of “ho” as either “hos” or “hoes.” Where do you turn if it’s not in the dictionaries of record?

When a word is not in Webster’s or Random House, I will look online. There are many dictionaries of slang, but you have to choose your source carefully. One of our sources is the New York Times, but of course it’s no good for profanity! One feels so silly looking up “jism,” say (though there are variant spellings), and even sillier querying it. You try to find a respectable source for the profanity, and it is a bit of a challenge. Rap lyrics, especially.

You once had a dialogue with James Salter probing his somewhat-unusual use of commas. He had clear, if idiosyncratic, reasons for his choices. There’s something very personal about punctuation choices and a person’s particular syntax.

Yes, James Salter was incredibly generous and patient in his explanations, and I was touched by how important those distinctions are to him. Punctuation can work like gesture, and it’s very individual. So is syntax—that’s style, and it’s a reflection of personality.

What makes for a good copy editor?

If there’s a combination that makes an ideal copy editor it’s high intelligence and low ego, because if you’re looking for ego gratification copy editing is probably not the place to be.

You’re pretty low on the totem pole. And yet it demands vigilance and a good fund of general knowledge that sometimes you can find a use for when you’re reading a piece. I once caught a mistake in Middle English. I’d taken Chaucer in graduate school.

Another thing that’s important is the capacity for self-doubt. You have to be willing to admit that you might have missed something. If you think Well, that's that, I've done a perfect job here, when you look over a piece again you're conditioning yourself to not see anything that you missed because you’re spending your energy persuading yourself that actually you're perfect, right? It's crazy to say it, but self-doubt is kind of a virtue in this job.

I have a theory that Catholic school alums are more suited to copy editing than others. Did you go to Catholic school?

Oh yeah. All the way through twelfth grade. I went to a Catholic high school.

Me, too. I remember there was a lot of grammar and one year that seemed to be entirely devoted to diagramming sentences. Plus, Catholicism emphasizes humility and as you pointed out the copy editor has to have that quality of self-doubt.

Yes, that’s true. I do sometimes feel like I am invoking that humility.

I suffered from terrible envy of writers for a long time. But it’s an occupational hazard to writers. All you can do is do what you do, and realize that envy is going to hurt you and make you bitter. It’s better to do go out and get that thing yourself—turn it around somehow.

That's what I’ve tried to do. I knew I wanted to be a writer, and I was dealing all the time with other people’s writing, and it was especially hard in those early years when I was on the copy desk and I was trying to write for Talk of the Town, because I’d turn in a piece and that week when the pieces came through to be set up for Talk of the Town, of course I thought, oh, those pieces all sucked! They weren’t anywhere near as good as mine! But finally you learn, and you’re grateful that some of those terrible things were not published.

What were you working on then?

I was always trying to get a story out of my own interests. In those days, I was in my Greek period; I was studying Greek and traveling in Greece. And I submitted these stories to William Shawn, unsolicited, which was really quite hopeless! After one quite long piece that I submitted, dear William Shawn actually came back, gave me a check for it, and told me no way were they ever going to run it! So I was bummed out, I probably got drunk that night, but the next morning I had another idea, and the next time I submitted a story he took it and ran it. So you just keep going.

What kind of response have you gotten to the book so far?

After the book excerpt ran in the magazine, I got a lot of mail—some of it was entirely complimentary. But most of it got to a point where it said, “But I noticed you had…” Somebody didn’t like a split infinitive. Some people examined my commas with a magnifying glass and found inconsistencies between what I said about comma usage and what I did. And I got a scathing letter of complaint about my calling Aldus Manutius the inventor of the comma: apparently it had already been around a while before him!

The book got a great write-up in the New Republic that touched on the class system among people who work in editorial offices, with those in charge of copy editing at the lower end. Does this ring true for you?

I found that review so satisfying because the reviewer so got it. When I was on the copy desk in the ’80s, and all I did was change spellings, I was privy to the kinds of mistakes a writer made. Sometimes I would enjoy feeling a sense of superiority, in the wee hours of the night when I was copy editing their stuff. But it’s all part of an age-old, traditional system where you’re part of a team, and it’s just what you do. You wouldn't have a job if the writers didn't make some mistakes, right?

It’s something I feel lucky to be doing and to have done all these years because I'm better at it than I would be at say, waiting on tables. It uses something that I have a facility for. But I did identify with the author of the New Republic piece—it is kind of a class system. Though I think at the New Yorker we are valued pretty highly.

There probably were times in the past when I made a catch, and thought I deserved some kind of prize! But in fact that’s what I'm getting paid to do. I’m actually in a good spot. What we do is, we're like gadflies. We can point things out, or make a suggestion. It’s not personal. You just are as honest as you can be in your reaction to the piece.

Did you ever think about changing your career, or going elsewhere?

I did depart for a while. There were a lot of changes at the New Yorker in the late ’80s, when it was taken over by Condé Nast. And then William Shawn was forced out at the age of eighty-something, and Robert Gottlieb came in. I did leave after a year under Gottlieb. He was a good editor. I just didn't have any rapport with him. I was offered a job at a start-up magazine, where I got to set style. I also got to write, and I got to edit, to develop pieces, and that was very satisfying. I made mistakes and I developed a judgment I didn't have before. Then I spent two years freelancing. But it got to me. I like a regular paycheck and paid holidays!

So when an opening became available I came crawling back. I wasn’t sure it was what I wanted to do, but when I learned I got the job I was very happy. So I was away for four years. I came in ’78 and left in about ’89 and I came back on staff as a page OK’er in ’93. And I've been here ever since. I think it was the second day after I came back that the announcement came that Tina Brown would be taking over from Bob Gottlieb. That was an interesting day.

I guess so.

A lot of people think Tina really did good things for the magazine. And she did do some good things. But all the while Tina was here I just kept my head down! Just did the work and let everything swirl over me.

I remember a lot of articles about Roseanne Barr.

Yeah, it made a stink around here when Roseanne Barr was invited to be the guest editor! Some of the writers thought, “You can't be serious.” But of course it wasn’t serious.

What was it like working under Tina Brown?

She liked to tear up the magazine and put in new articles at the last minute, so there were some very late nights under Tina. Under William Shawn, of course, it was all very stately! The magazine was planned five weeks in advance. Of course, sometimes the pieces were ninety columns long so you couldn’t possibly have done them in one week. But now we’ve kind of achieved an equilibrium where they’re planned ahead, not five weeks ahead, and we could use more time—but I like what David Remnick does. Since 9/11 essentially, David has given us a sense of mission. We feel like we’re part of the world. He is a newspaper man, so he likes things that are timely. Though I sometimes do miss those pieces the old New Yorker was famous for, that really had nothing to do with anything. They were just a pleasure to read.

Has being a copy editor affected how you write?

I try not to let it—it will just slow me down. Writing and copy editing are two very different things. It’s not really the writer’s job to learn from their mistakes—that’s why there are editors to fix them. But while I was trying to learn to be a better proofreader or a better copy editor, at the same time I was writing. It was paralyzing—trying to be a query proofreader on my own stuff. Eventually you would just nibble it down to nothing; there was something wrong with everything. So I’ve learned to write without worrying about mistakes.

What’s it like to have your own work copy-edited?

When I was writing Talk of the Town stories under William Shawn, it was the hardest thing when my own pieces were “Goulded”—that’s what we called it. The proofreader Eleanor Gould had her own verb. I felt like I was on a torture rack: the piece was being stretched and its bones being reset. I wasn’t sure its bones had been broken and needed resetting. But she was working by her own lights, and that’s all we got, you know?

Shares