The television and other media coverage of the protests in Baltimore has shown one longtime observer that the way we look at urban uprisings hasn’t changed much in 50 years. But the shifts in politics and the media landscape since the Watts riots and other sites of unrest in the 1960s means some of it resonates a bit differently.

“There are standard frames” for covering this sort of thing, says Todd Gitlin, a media critic at Columbia University and author of the unsentimental and important book “The Sixties,” much of which looked at youthful protests and the New Left. “The dominant frame is, ‘There’s terrible violence, and it’s generated by people who are irresponsible' – maybe they’re 'thugs,' as the mayor said in an unguarded moment. Or they’re one kind of criminal or another.”

Subthemes that are also typical – that go back five decades at least -- include the call for nonviolence by black leaders and media coverage of the besieged city's mayor as a figure “caught between” the two sides, he says.

Considering the way the media works is not tangential to understanding Baltimore. The vast majority of us following the chaos, after all, are not getting our information by looking out the window of our row house or by walking up North Avenue: We’re seeing it on television, watching videos online, hearing reports on the radio, or reading about it in newspapers and magazines. And just because media frames are often unintentionally established by networks and editors, and unconsciously consumed by readers and audiences, doesn’t mean they don’t exert their pull on us.

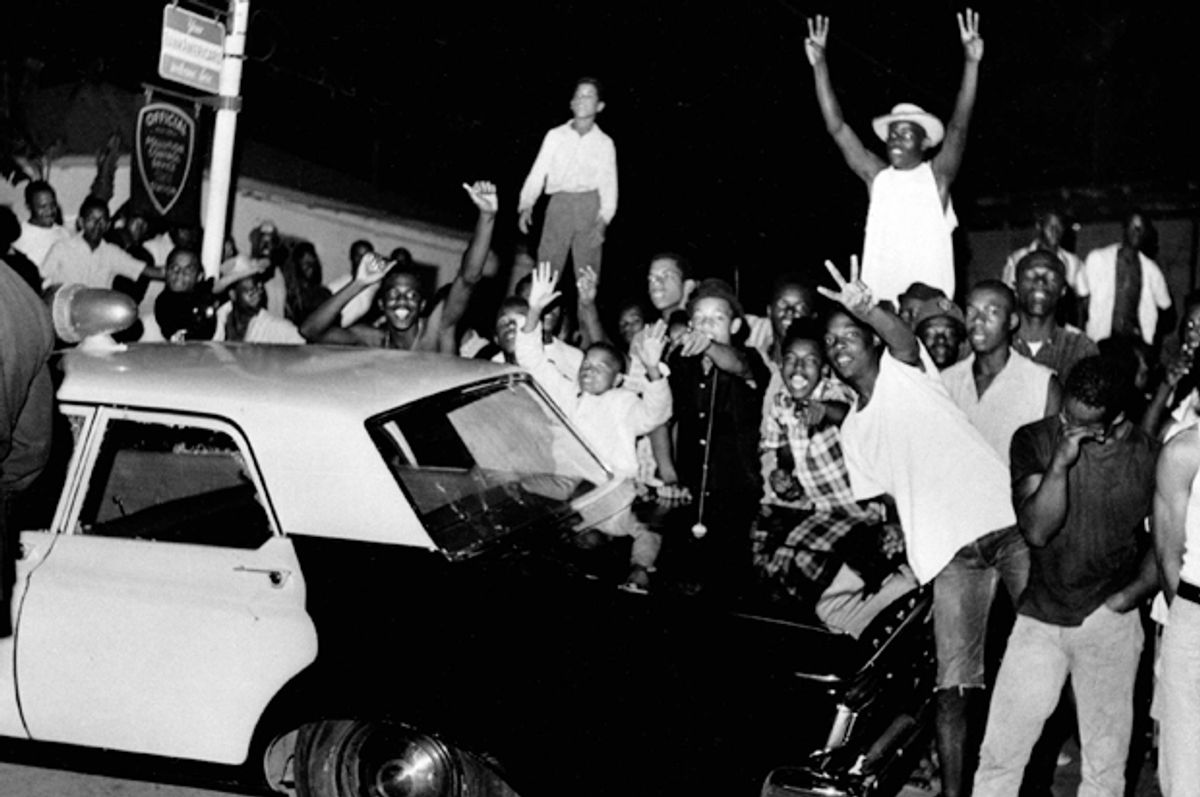

Coverage out of Baltimore, Gitlin says, is full of if-it-bleeds-it-leads imagery: “Pictures of smashed glass, police cars burning or turned over, footage of rioters making away with stuff from stores… This is the standard lead; we’ve had it for 50 years.”

It’s not that this stuff doesn’t happen, he says, but the way the coverage is structured. “The standard framing of a political-rebellion story is as a crime story: Somebody has uprooted the order, and order has to be restored. It’s a ritual of reassurance,” and resembles the way earthquakes, tsunamis and other natural disasters are covered.

We’re getting another kind of frame, he says, one that concentrates on segregation, the economic starving of neighborhoods, and other root causes. Some of this has appeared in New York Times stories on the decimation of West Baltimore neighborhoods, or in an American Prospect piece on how segregation led to Ferguson. But this kind of thing doesn’t show up on television very often.

And here’s where we’re in a different world than we were in the 1960s. Politically it was a strange time: The counterculture was thriving, the Great Society was alive, if not well, and a law-and-order brand of conservatism – which would bring Nixon into office – was growing. It would also help a GE spokesman in his run for California governor: “In 1966, he’s running against rioters and crazy kids,” Gitlin says of Ronald Reagan’s denunciation of both the unrest in Watts and the Free Speech movement at University of California, Berkeley.

But even though television was far more limited back then – mostly just three major networks, trying to play its coverage straight down the middle – it was often more attuned to context and the big picture. “In ’68 or ’69, there would have been network documentaries,” he says. “They would have made an effort to talk about the race and class situation. They would have been earnest and insufficient, but they would have made an effort.”

There was also a larger sense in the '60s that there was “two Americas” and that opportunity had to be opened up for those left behind. The Kerner Report – commissioned by the Johnson administration in 1967, as Detroit burned, released a year later, around the time of the riots that followed Martin Luther King’s assassination – tried to get at root causes of urban unrest, and saw lack of economic options for black people as being the major factor. “The media was singled out in the Kerner Report,” Gitlin says. "They not only wanted the rioters to cool it, they wanted the media to cool it.” The Nixon administration that followed Johnson’s was even sterner in lecturing the press and media for what it saw as overcoverage.

But what we need now, says Gitlin, is stories and programs that look at jobs (and lack thereof), school budgets, the criminal justice system, and the legacy of legally enforced and informal segregation.

“These are all elements of a story – they are not free-standing. It takes a lot of work, and that kind of work is costly. I’m not sure the networks want to make that kind of investment. But if you were really trying to convey what was going on, you’d have to paint a very big picture.”

Shares