When Oscar Grant was shot by transit cop Johannes Mehserle in Oakland in the early hours of January 1, 2009, a week passed with no institutional response, while videos of Grant’s murder spread on YouTube like a prairie fire. Then people rebelled, rioted, and took over the streets of Oakland twice—on January 7 and January 14—and just like that, and with the threat of another rebellion hanging heavily in the air, the mayor and the governor leaned on the Alameda County district attorney to bring charges.

When Mike Brown was gunned down by Darren Wilson in Ferguson, Missouri on August 9, 2014, the community exploded in massive and sustained resistance on the streets. Aside from galvanizing public opinion and sparking a national movement against white supremacist policing, this street insurgency first forced the replacement of Ferguson PD by the St. Louis County Sheriff, and later bythe state Highway Patrol, as well as prompting both a federal investigation and a grand jury considering—but ultimately rejecting—Wilson’s indictment for murder.

And when Freddie Gray died on April 19, 2015, after a week in a coma provoked by Baltimore City Police, we all know what happened next: in a wave of resistance rivaling Ferguson in the national attention it garnered, Black youth across Baltimore responded as directly as possible to those terrorizing their communities, in some cases chasing the “forces of order” out with bricks. After nearly a week of resistance—including the occupation of Baltimore by heavily-armed National Guard—Maryland state’s attorney Marilyn Mosby stepped into the fray, announcing charges against six officers and admitting that her hand had been forced by the streets: “To the people of Baltimore and the demonstrators across America: I heard your call for ‘No justice, no peace.’”

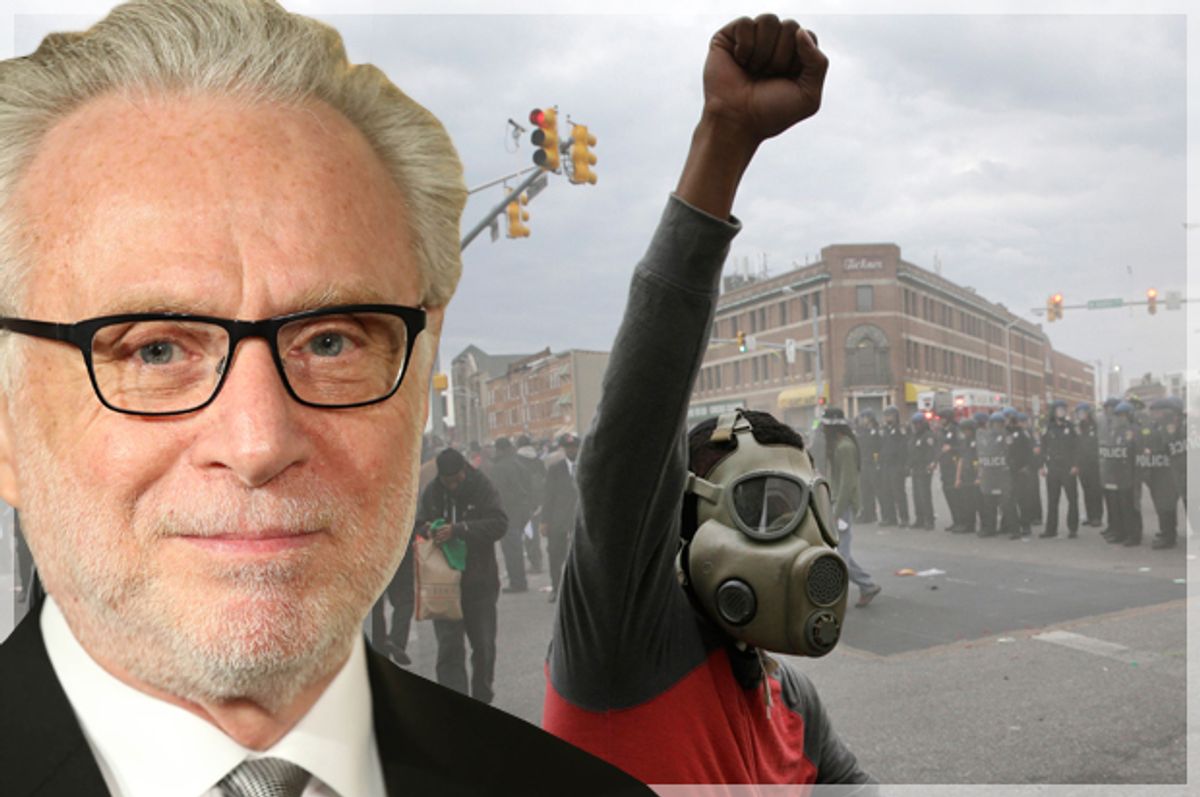

Riots work. But despite the obviousness of the point, an entire chorus of media, police, and self-appointed community leaders continue to try to convince us otherwise, hammering into our heads a narrative of a nonviolence that has never worked on its own, based on a mythical understanding of the Civil Rights Movement. In their zealousness, however, scripted motives can slip out, as with Wolf Blitzer’s bullying of Ferguson organizer DeRay McKesson on live television. Blitzer insisted no fewer than five times that McKesson denounce the rebellions, only to show his hand with the words—astounding from a so-called “journalist”—“I just want to hear you say…”

While the mainstream media—and CNN in particular—has sought to uphold a narrative of nonviolence, it simultaneously carried water for a brutal Baltimore City Police Department, which is after all the only force in question guilty of taking a human life (indeed many). Via twitter, the Baltimore City PD disseminated a counterinsurgency narrative that the media unhesitatingly parroted: first that the riots were sparked by “outsiders,” and when that narrative fell unsurprisingly flat, that those involved were—in the quickly-retracted words of Mayor Stephanie Rawlings-Blake—“thugs.” (Bear in mind that BCPD Commissioner Anthony Batts is an outside agitator if ever there was one, who not long ago imposed racist and unconstitutional gang injunctions and curfews in Oakland, as well as apparently being a repeat domestic abuser.)

In fact, the now-dominant claim that Freddie Gray was attempting to injure himself in the police van only reached the Washington Post through a sort of perverse game of telephone: a police affidavit attesting to the alleged statements of an anonymous inmate. That the Post printed such a dubious and circuitous claim—one contradicted by medical evidence, investigative journalism, and the anonymous source himself—is a testament to the putridity of the paper’s standards. (I won’t even address the asinine media narrative surrounding a so-called “purge.”)

Perhaps most revealing was the police response to a citywide truce between the Bloods, Crips, and Black Guerrilla Family. What would seem to be an unambiguously good thing was quickly denounced by BCPD in a misleading (read: mendacious) statement declaring the truce a “credible threat” and suggesting that gang members had teamed up to “take-out” police. This last phrase, which appears in quotation marks in the police statement, was never attributed to an actual source, and for a very simple reason: because it was a fabrication that gang members immediately denounced. This was not a poor decision by Baltimore Police, but instead a well-worn strategy: the LAPD said exactly the same thing when Bloods and Crips declared a truce in 1992, and then they did everything they could to “sabotage and undermine the truce.”

Riots work, so why do so many well-meaning voices continue to insist that they don’t? The argument that they harm communities makes intuitive sense, but doesn’t hold up to serious scrutiny: the Maryland Insurance Commission has estimated the uninsured losses from the riots to be a paltry $1 million. Meanwhile, foreclosures from the recession cost Baltimore $1.5 billion (with a B) from 2008-2010, and $13.6 million in tax revenue in 2010 alone. And as many are quick to point out, the city has paid out more than $5.7 million to settle police abuse lawsuits since 2011. The police—not to mention capitalism—have done far more to damage Baltimore than any riot could.

Some insist that riots only provide a ready-made image to the media that emphasizes the “negative” over the “positive” (meaning the “violent” over the “peaceful”). But this view has little to say about whether so-called “peaceful” protests are effective in bringing attention to police murder, offering instead a moral imperative: the media should cover peaceful marches, the system should respond. But they don’t, and it doesn’t, and if so-called peaceful tactics don’t bring change, then they lose their status as a “positive” alternative, and even become complicit in continued systemic violence.

Tragic facts are facts nonetheless: we aren’t talking about Baltimore—and we weren’t talking about Ferguson—simply because Freddie Gray and Mike Brown were killed there. In a system built upon the death of Black bodies, such death is not newsworthy. #Baltimore and #Ferguson are trending hashtags because they are places where people decided they had had enough, and took over the streets to transmit that message in no uncertain terms. While riots can undeniably win concrete concessions, it is this demonstration effect that matters most, despite being more long-term and difficult to measure, making Ferguson a catalyst for militant resistance nationwide. No matter how much we try to convince ourselves that history moves forward gradually in that inevitable tendency we like to call “progress,” the reality has always been more erratic and jarring, combative and conflictive, driven by just this sort of militancy against all odds.

Frantz Fanon insisted that to break the smooth surface of white supremacy requires something more than peaceful protest. It requires the explosive self-assertion of the oppressed, through which the oppressed themselves can come to understand their own power. When people take history into their own hands, they remake themselves as they remake that history. After Ferguson, many previously apolitical local residents were transformed and began to view themselves as part of a broader, national movement. Some, like Jameila White, walked a mile every day to support the Ferguson rebellion. And what could be more empowering for systematically excluded and harassed youth in West Baltimore than chasing the police out by force?

But Fanon was equally aware of the containment and counterinsurgency strategies that both Ferguson and Baltimore have inevitably generated. It’s not that the political opportunists and ambulance-chasers—the Al Sharptons of the world—misunderstand the power of riots. In fact, they understand it all-too-well, knowing that the threat posed by the people in the streets is their best ammunition when begging for crumbs from the system. Writing during the Algerian Revolution, Fanon showed that those who come out of the woodwork during a rebellion, positioning themselves as mediators and moderate voices—in short, as nonviolent—do so in a bid to reinforce their own authority:

Nonviolence is an attempt to settle the colonial problem around the negotiating table before the irreparable is done, before any bloodshed or regrettable act is committed. But if the masses, without waiting for the chairs to be placed around the negotiating table, take matters into their own hands and start burning… it is not long before we see the “elite” and the leaders… turn to the colonial authorities and tell them: “This is terribly serious! Goodness knows how it will all end. We must find an answer, we must find a compromise.”

So too today: “unable to foresee the possible consequences of such a whirlwind” groups like the National Action Network “fear in fact they will be swept away,” and so offer their services in groveling deference to the state: “We are still capable of stopping the [rebellion], the masses still trust us, act quickly if you do not want to jeopardize everything.” Even the power granted to such opportunists exists not despite riots, but because of them.

Writing in The Atlantic, Ta-Nehisi Coates recently called the bluff of the preachers of nonviolence in a stunning fashion, insisting that: “When nonviolence begins halfway through the war with the aggressor calling time out, it exposes itself as a ruse. When nonviolence is preached by the representatives of the state, while the state doles out heaps of violence to its citizens, it reveals itself to be a con.” In a recent NPR interview, however—in which Robert Siegel’s badgering was only slightly more polite than Wolf Blitzer’s bullying—Coates laughs off comparisons to Fanon, instead insisting that his goal is not to question nonviolence, but simply to call the bluff of those who insist on nonviolence while brutalizing Black communities. But by attempting to leverage hypocrisy to impose ethical behavior on a white supremacist state, Coates runs the risk of neglecting a very Fanonian insight that his own writing often confirms: namely, that under conditions of white supremacy, ethics is impossible.

By admitting that she was responding to the upsurge in the streets of Baltimore, Marilyn Mosby said what is normally left unsaid, and made perfectly clear what is supposed to remain hidden: that the only “credible threat” that matters to police and political elites is the threat posed when communities take to the streets. For having admitted this, Mosby is paying the price both in the media and in attacks from the Fraternal Order of Police, for whom any scrutiny of police is too much (she is also, arguably, providing fodder for a judge to ultimately toss out some of the charges as “politically motivated”).

But to lionize a state’s attorney under such circumstances is to make a serious mistake, and if street rebellions can lead to partial victories, we need to remember that these victories are just that: partial. Reminders of this abound. After all, all six of the officers charged are out on bail, while 18-year-old Allen Bullock is still being held for allegedly smashing a cop car. That Bullock’s bail is higher even that of the BCPD officer charged with “depraved heart” murder tells us all we need to know about just how much #BlackLivesMatter. And let’s not forget that, as crowds celebrated Mosby’s announcement in the streets of Baltimore, they were brutalized and arrested en masse under a curfew that has only now been lifted. Every concession is at the same time a containment strategy.

In the end, Johannes Mehserle served less than a year for murdering Oscar Grant. Darren Wilson, George Zimmerman, and so many others walk free. And there is little reason to expect the second-degree murder charge to hold up in Baltimore, just as—as absurd as it sounds—there is no guarantee that Michael Slager will be convicted for murdering Walter Scott in cold blood. But without the threat of insurgency in the streets, no charges would ever have been brought in the murder of Freddie Gray—and if in the euphoria of celebrating the arrests, we forget that they measure not the justice of the system but our own power in the streets, then all is lost.

Shares