New York Mayor Bill de Blasio took his progressive agenda road show to Washington Tuesday, where he was trailed by local and national reporters in the fever grip of a narrative: How can de Blasio be a leader on national issues when the problems of his city aren’t solved? What about the people hit on the head with hammers in Union Square while the mayor was gallivanting about on Tuesday? What about the carriage horses?

These were real questions put to de Blasio after a rather surreal event in which progressive leaders endorsed an agenda to tackle income inequality in early-May 90-degree heat, without any shade, just outside the Capitol. You could see all the promise and all the contradictions of the progressive movement in the sun-baked tableau. An actual story was on display, even as reporters chased non-issues and their cherished narrative. Debate buzzed around the overheated podium as dozens of Democratic Congress members, labor leaders and civil rights activists declared their support for the 13-point “Progressive Agenda to Combat Income Inequality” emblazoned on a poster beside them.

De Blasio was flanked by big placards supporting debt-free college and expanding Social Security, two demands that have rocketed to the top of the progressive agenda thanks to strong movements behind them. But those issues haven’t yet officially made the 13-point list. A bigger omission was any mention of criminal justice reform. Organizer Van Jones amiably grumbled about the lack of an official agenda item as he caucused with concerned friends, who seemed bewildered by the omission, though Jones wholeheartedly endorsed the agenda when it was his turn to speak.

“We are going to go back to the coalition literally starting tomorrow and add a couple of the pieces, obviously with the agreement of coalition members, that people have said they thought would be very important,” de Blasio promised the crowd. He’s going to have to.

Meanwhile, as the event got underway, Senate Democrats were thwarting President Obama’s attempt to fast-track deliberation on the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade accord, an issue that’s both energizing and dividing the left, including the coalition behind de Blasio’s agenda. Labor leaders railed against TPP from the podium; Rev. Al Sharpton, who supports the pact, preached “unity, not unanimity,” and reminded the crowd that left-wing infighting in 1968, the year Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was assassinated, and a teenage Sharpton joined the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, elected Richard Nixon.

The long day ended with a devastating Amtrak derailment outside Philadelphia, killing at least seven people on a train that I was almost aboard. (I caught the last train to New York.) I suppose that concentrated my mind on this allegedly progressive moment.

The crisis couldn’t be more clear: Infrastructure used to be an easy, bipartisan issue. Now, as a nation, we’ve gone from debating high speed rail, to cutting funding for low-speed rail, to tolerating no-speed rail this week along the Northeast Corridor, where de Blasio’s New York will lose $100 million every day train travel is halted. News that the engineer was going 100 miles an hour, way over the advised speed for that stretch of track, doesn’t change the fact that too many antiquated stretches of track require much less speed than is customary for train travel around the world. Or that "positive train control" technology, which should have already been installed, hadn't been there. The tragedy ought to muzzle reporters who robotically ask why New York’s mayor traveled to Washington, not only to lobby for federal action but to rally a new political coalition that can fix our broken politics. But it probably won’t.

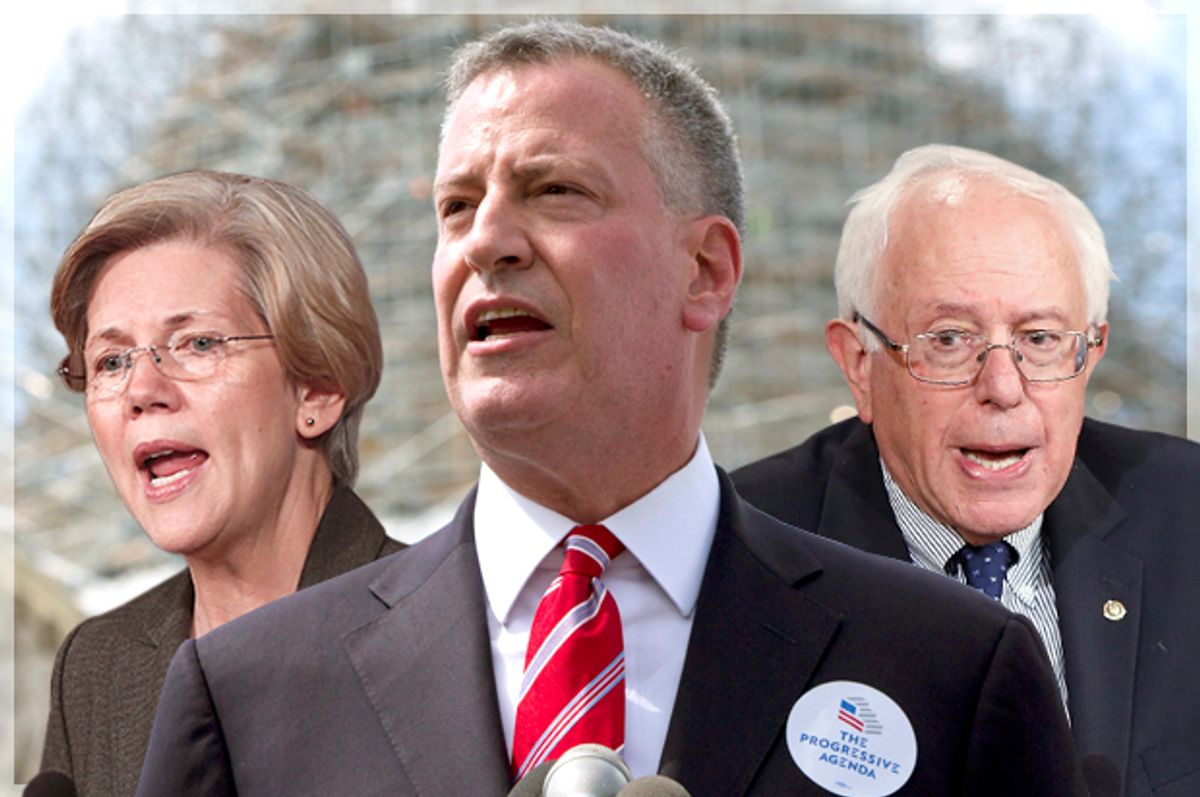

Progressives have a moment, all right, but are they up to it? My day with de Blasio provided some answers, not all of them encouraging. The New York mayor’s effort is widely perceived as an attempt to pull Hillary Clinton to the left, in the absence of a strong primary challenger. (It got underway before Sen. Bernie Sanders announced his candidacy, but Sanders, alone, probably isn’t much threat to the front-runner.) The debate over its agenda shows that progressives care, passionately, about the 2016 election, and beyond. They believe they can drive the debate.

But first, they might have to get out of their own way. As the Obama era comes to a close, they are still grappling with the issues of race, and not always well. There are lessons here for Hillary Clinton, though maybe not the ones de Blasio and allies intended.

* * *

My big day of progressive politicking began with a National Press Club event to release a new report by the lefty-wonky Roosevelt Institute, “Rewriting the Rules of the American Economy: An Agenda for Growth and Shared Prosperity.” Roosevelt economist and Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz called it “a big think,” and he’s right. The event was keynoted by Sen. Elizabeth Warren and de Blasio. You could see many of the assets of 2015 progressive organizing on display.

For one thing, there’s rare bipartisan agreement that income inequality is growing, and that it’s a problem, although Republicans continue to advance only warmed-over Reaganism as a solution. There’s also growing recognition among liberals that their efforts must go beyond tinkering at the margins of the economy while venerating the allegedly “free” market. Markets aren’t magic; they’re created by socially constructed rules. “Rewriting the Rules” meticulously shows how the economic “rules” laid down by government in the years after World War II deliberately spread prosperity. Then, starting in the late '70s, our rules began to concentrate it.

“If someone said in the 1980s, ‘we’re going to change the rules, and all the income gains will go to the top,” nobody would have supported that, Stiglitz told me after the event. That’s why there’s an opening now to “rewrite the rules,” in the Roosevelt Institute’s phrasing. “It wasn’t an act of God,” de Blasio told the crowd. American political leaders made political decisions to intensify income inequality; they can make different ones.

A third boon to progressive politics is the fact that there’s an agenda widely supported by liberals (and according to polls, by the general public too). It involves efforts to shore up families with paid family leave and early childhood programs; boosting pay by hiking the minimum wage and strengthening labor rights, particularly the right to organize; and a range of progressive taxation ideas, including eliminating lower rates for wealth than work. Roosevelt’s agenda got a little bit into the weeds, but by necessity; de Blasio’s stayed focused on broader demands.

Finally: these demands are bolstered by rising grass-roots movements. There’s more on-the-ground activism -- around fast-food workers’ wages, the “Fight for $15” campaign, Wal-Mart workers’ rights -- than I’ve seen on the left in a long while. In their remarks at the Roosevelt event, both de Blasio and Warren referenced the grass-roots energy as a resource progressives must harness.

Yet I was surprised that neither referred to what might be the most vibrant and important movement of all: the organizing around “Black Lives Matter” and the effort to end the era of mass incarceration. De Blasio’s Progressive Agenda didn't mention criminal justice reform or anything related to it; the Roosevelt Institute report, laudably, does include a bullet point recommending "Reform the criminal justice system to reduce incarceration rates," but it's one of 37 recommendations and easily missed (mea culpa; in an earlier version of this post, I missed it). I’ve worked on these issues my entire career, and I’ve got to say: Sometimes I’m amazed at the white left’s blurry vision when it comes to race.

I asked de Blasio about that omission when we met briefly on Tuesday afternoon.

“I think this agenda, and this coalition, is going to grow,” he told me. “We have to connect the fact that income inequality is deeply connected to mass incarceration, that racism underlies the lack of opportunity for men of color. I think those two issues go naturally together and I’m going to be putting a lot of time into them.”

But there was a lot of discontent with the omission from the 13-point agenda when we got to the official event, which almost fell apart over the controversy. Van Jones, rather admirably, fell on his sword when I asked him about it by phone the next day. Like a lot of black progressives, he’s been focused on the situation in Baltimore, in the wake of Freddie Gray’s killing by police, and wasn’t entirely on top of the drafting of the agenda.

“I was one of the people who was at the initial Gracie Mansion event,” he told me, carefully, on Wednesday afternoon. “In the drafting of the agenda, I was not as attentive or involved as earlier, because of Baltimore. I didn’t do my due diligence on the back end. I appreciate that the mayor made a commitment to go back to all the parties on a ‘schools not jobs’ plank.” But I found myself wondering why the issue required a push from Jones, anyway, given its centrality to the opportunity crisis in America.

Meanwhile, just yards away from the de Blasio convening, Obama lost a round on the TPP. New York’s mayor stood squarely with the Massachusetts senator on the issue. “The bottom line on trade is I couldn’t agree more with Elizabeth Warren,” he told the crowd.

But there was an ugly parallel dust-up. Sen. Sherrod Brown – who’d attended the inaugural meeting of de Blasio’s effort at New York’s Gracie Mansion in early April, but wasn’t at the Capitol event – lamented the president’s very personal attacks on Sen. Warren, suggesting they might even be a little bit sexist. The president, Brown noted, has attacked Warren by her first name, "when he might not have done that for a male senator, perhaps?"

I didn’t read Obama’s Warren comments as sexist – he regularly refers to Vice President Biden as “Joe” -- although I thought they were weirdly personal and politically counter-productive. But I also didn’t read Brown’s criticism of Obama as reflecting racial animus – but Obama die-hards online did, with one perhaps parody Twitter account claiming the president had been “Emmett Tilled” for allegedly mistreating a white woman.

It reminded me that the fault lines of the 2008 primary campaign still exist, even as Democrats appear remarkably united, compared to the fractious 2016 GOP field, which is currently embroiled in a dead end debate about Iraq. (Poor Jeb.) And those fault lines weren’t closed, in any way, by the omission of criminal justice reform from the de Blasio agenda.

* * *

The stillness at the center of this storm is, oddly, Hillary Clinton. Many observers and even some participants see de Blasio’s project as an effort to pull her left. Now that she’s in the race, she’s arguably to the left of de Blasio’s agenda, given her recent policy statements calling for an end to mass incarceration, and promising to protect even more undocumented immigrants from deportation than are covered by Obama’s executive orders.

Pointing to the new divisions in the Democratic Party over trade, MSNBC’s Luke Russert asked de Blasio whether he thought Clinton had to stand with Warren on the TPP to win his group’s support. De Blasio ducked a direct answer, even as he declared his own support for Warren’s stand.

I asked de Blasio if he could see any scenario in which he didn’t endorse Clinton. “I don’t do hypotheticals,” he told me. When I laughed at that, he added, “But I can say honestly, I’m optimistic…She gave the speech on immigration, which I thought was great, the speech on criminal justice reform I thought was great. I think we’re seeing a lot. I still want to hear the core agenda for fighting income inequality, but this is a very promising start.”

Part of me thinks the best thing de Blasio can do to advance “the core agenda for fighting income inequality” is to be a great mayor of New York. But I’m also sympathetic to both his genuine need to harness federal support, in order to be a great mayor, and also to harness the impressive populist energy that fueled his unlikely rise to Gracie Mansion.

Given the controversy roiling around him on Tuesday, de Blasio maintained an enviable equanimity. In the end I found myself thinking he has the temperament to play a role in harnessing the energy of the fractious left, because he smiled and nodded his way through Tuesday’s event. He affably fielded dumb media questions in the 90-degree heat, while things were even hotter inside his own coalition, given the neglect of criminal justice reform on his agenda. Still, I can’t help thinking: The man who won office at least partly because he’s Dante’s father shouldn’t be struggling through an unforced error around an issue of race.

Shares