Sen. Bernie Sanders, the lifelong crusader for economic justice now running for the Democratic presidential nomination, has serious civil rights movement cred: he attended the historic 1963 March on Washington, where Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and a quarter million people changed the country’s course when it came to race. It would be wrong and unfair to accuse him of indifference to issues of racial equality.

But in the wake of his picture-postcard campaign launch, from the shores of Vermont’s lovely Lake Champlain, Sanders has faced questions about whether his approach to race has kept up with the times. Writing in Vox, Dara Lind suggested that Sanders’ passion for economic justice issues has left him less attentive to the rising movement for racial justice, which holds that racial disadvantage won’t be eradicated only by efforts at economic equality. Covering the Sanders launch appreciatively on MSNBC, Chris Hayes likewise noted the lack of attention to issues of police violence and mass incarceration in the Vermont senator’s stirring kick-off speech.

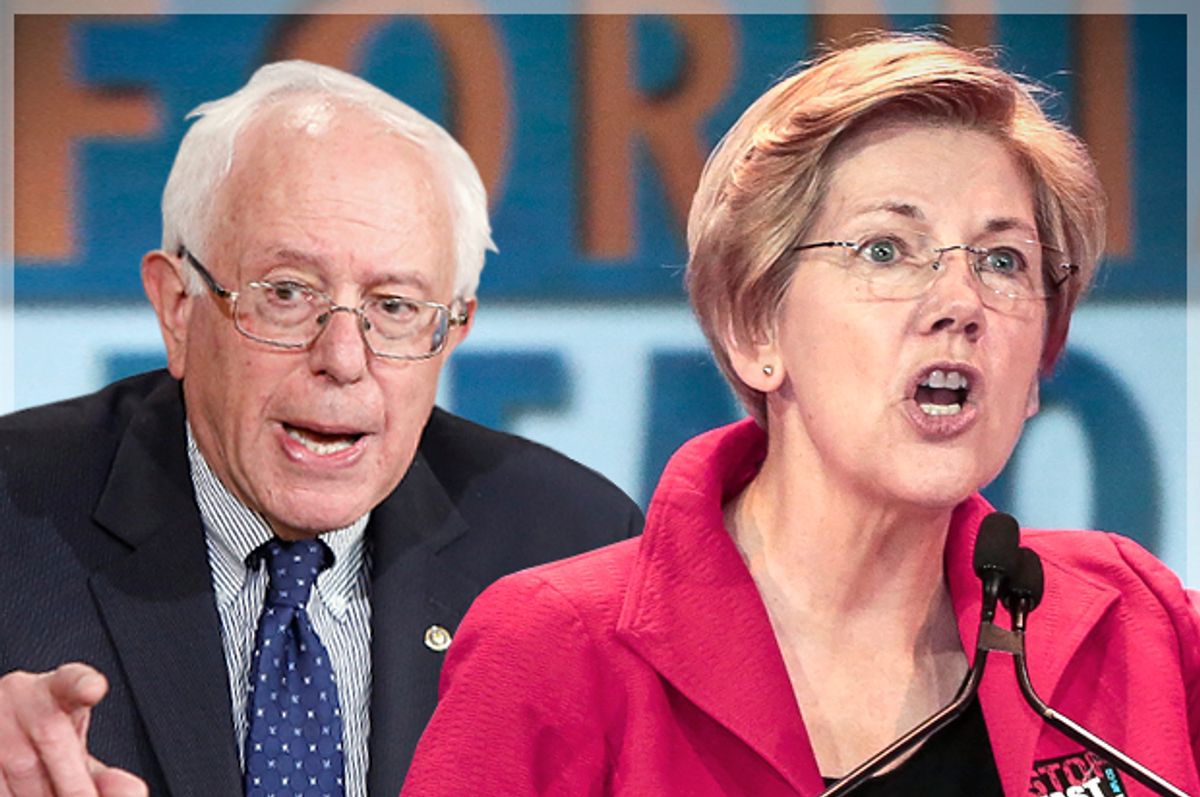

These are the same questions I raised last month after watching Sen. Elizabeth Warren and New York Mayor Bill de Blasio hail the new progressive movement to combat income inequality at two Washington D.C. events. Both pointed to rising popular movements to demand economic justice, most notably the “Fight for $15” campaign. Neither mentioned the most vital and arguably most important movement of all, the “Black Lives Matter” crusade. (Which is odd, since "Fight for $15" leaders have explicitly endorsed their sister movement.) And the agendas they endorsed that day made only minimal mention, if they mentioned it at all, of the role that mass incarceration and police abuse plays in worsening the plight of the African American poor.

Looking at the overwhelmingly white Bernie Sanders event last week, I saw it again: the rhetoric and stagecraft employed by white progressives whom I admire too often –inadvertently, I think -- leaves out people who aren’t white. Of course, Sanders’ home state of Vermont is 96 percent white, so his kickoff crowd predictably reflected that. But his rhetoric could have told a more inclusive story.

So could Elizabeth Warren’s. I love her stirring stories about her upbringing: the days when her mother’s minimum wage job could support a family, when unions built the American middle class, and when Warren herself could attend a public university for almost nothing. Like a lot of white progressives, she points to the post World War II era as a kind of golden age when income inequality flattened and opportunity spread, the result of progressive action by government. I’ve written about the political lessons of that era repeatedly myself.

But the golden age wasn’t golden for people who weren’t white. Yes, African American incomes rose and unemployment declined in those years. But black people were locked out of many of the wealth-generating opportunities of the era: blocked from suburbs with restricted covenants and redlined into neighborhoods where banks wouldn’t lend; left out by the GI Bill, which didn’t prevent racial discrimination; neglected by labor unions, which discriminated against or outright blocked black members. (That’s why I gave my book, “What’s the Matter with White People?”, the subtitle “Why We Long for a Golden Age that Never Was.”)

Conservatives look back at those post-World War II years as a magical time when men were men, women raised children, LGBT folks didn’t exist or stayed closeted, and the country was white. Progressives point to the government support that created that alleged golden age, but they too often make it sound rosier than it was for people who weren’t white. In fact some of those same policies of the 1950s helped create the stunning disparities between black and white family wealth, which leaves even highly paid and highly educated African Americans more vulnerable to sliding out of the middle class.

All of this leaves white progressives vulnerable to charges that they don’t understand the political world they live in today. “I love Elizabeth, but those stories about the ‘50s drive me crazy,” one black progressive told me after a recent Warren event.

Dara Lind points to Sanders' socialist analysis as a reason he's reluctant to focus on issues of race: he thinks they're mainly issues of class. She samples colleague Andrew Prokop's Sanders profile, which found:

Even as a student at the University of Chicago in the 1960s, influenced by the hours he spent in the library stacks reading famous philosophers, (Sanders) became frustrated with his fellow student activists, who were more interested in race or imperialism than the class struggle. They couldn't see that everything they protested, he later said, was rooted in "an economic system in which the rich controls, to a large degree, the political and economic life of the country."

Increasingly, though, black and other scholars are showing us that racial disadvantage won't be undone without paying attention to, and talking about, race. The experience of black poverty is different in some ways than that of white poverty; it's more likely to be intergenerational, for one thing, as well as being the result of discriminatory public and private policies.

Ironically, our first black president has exhausted the patience of many African Americans with promises that a rising economic justice tide will lift their boats. President Obama himself has rejected race-specific solutions to the problems of black poverty, arguing that policies like universal preschool, a higher minimum wage, stronger family supports and infrastructure investment, along with the Affordable Care Act, all disproportionately help black people, since black people are disproportionately poor.

At the Progressive Agenda event last month, I heard activists complain that they’d been told the same thing: the agenda will disproportionately benefit black people, because they’re disproportionately disadvantaged, even if it didn’t specifically address the core issue of criminal justice reform. (De Blasio later promised the agenda would include that issue.) But six years of hearing that from a black president has exhausted people’s patience, and white progressives aren’t going to be able to get away with it anymore.

Hillary Clinton could be the unlikely beneficiary of white progressives’ stumbles on race. The woman who herself stumbled facing Barack Obama in 2008 seems to have learned from her political mistakes. She’s taken stands on mass incarceration and immigration reform that put her nominally to the left of de Blasio’s Progressive Agenda on those issues, as well as the president’s. Clinton proves that these racial blind spots can be corrected. And American politics today requires that they be corrected: no Democrat can win the presidency without consolidating the Obama coalition, particularly the African American vote.

In fact, African American women are to the Democrats what white evangelical men are to Republicans: the most devoted, reliable segment of the party base. But where all the GOP contenders pander to their base, Democrats often don’t even acknowledge theirs. Clinton seems determined to do things differently, the second time around. The hiring of senior policy advisor Maya Harris as well as former Congressional Black Caucus director LaDavia Drane signal the centrality of black female voters to the campaign. In a briefing with reporters Thursday in Brooklyn, senior Clinton campaign officials said their polling shows she’s doing very well with the Obama coalition, despite her 2008 struggles – but she’s taking nothing for granted.

Pointing to Warren and Sanders’s shortcomings when it comes to racial politics doesn’t mean they’re evil, or they can’t learn to see things with a different frame. But they’re going to have to, or they’ll find that the populist energy that’s eclipsing Democratic Party centrists will be dissipated by racial tension no one can afford.

Shares