One of the more popular and enduring accounts of America’s past is that of its religious founding. Belief that the British-American colonies were settled largely by religiously devout people in search of spiritual freedom, that the United States government was founded in part on religious principles, that the Founders intended to create a “Christian nation,” and that America is a specially chosen nation whose success has been directed by divine providence has resonated in the national psyche for generations. Versions of this account have existed since the founding era and have persisted through times of national distress, trial, and triumph. They represent a leading theme in our nation’s historical narrative, frequently intertwined with expressions of patriotism and American exceptionalism.

Opinion polls indicate that many Americans hold vague, if not explicit, ideas about the nation’s religious foundings. According to a 2008 study by the First Amendment Center, over 50 percent of Americans believe that the U.S Constitution created a Christian nation, notwithstanding its express prohibitions on religious establishments and religious tests for public office holding. A similar study conducted by the Pew Forum on Religion in Public Life revealed even higher numbers, noting that “Americans overwhelmingly consider the U.S. a Christian nation: Two-in-three (67%) characterize the nation this way.” Other studies indicate that a majority of Americans believe that the nation’s political life should be based on “Judeo-Christian principles,” if the nation’s founding principles are not already.

Assertions of the nation’s religious origins and of divine providence behind the crafting of the governing instruments are especially popular among politicians. In fact, religious declarations by elected officials are so common today that they have become routine, if not banal. Frequently, allusions of God’s providence are ambiguous and are used simply as a ceremonial flourish, obviating the need for further elaboration. President Ronald Reagan, who was not a devout churchgoer despite his support from the evangelical Religious Right, regularly alluded to the nation’s providential past, remarking in one speech, “Can we doubt that only a Divine Providence placed this land, this island of freedom, here as a refuge for all those people in the world who yearn to breathe free?” One could argue that Reagan’s embrace of a providential past was uncritical, if not undisciplined: in his acceptance speech at the 1980 Republican National Convention, Reagan displayed his legendary disregard for consistency by declaring America to be “our portion of His creation” while praising the contributions of the deist Tom Paine! One particularly delicious statement is Dwight Eisenhower’s iconic remark that “our form of Government has no sense unless it is founded in a deeply felt religious faith, and I don’t care what it is!” Usually, such rhetoric does little more than affirm a national “civil religion,” where the nation’s institutions and its destiny take on an indeterminate, quasi-sacred quality. Such utterances largely fulfill a unifying, ceremonial purpose.

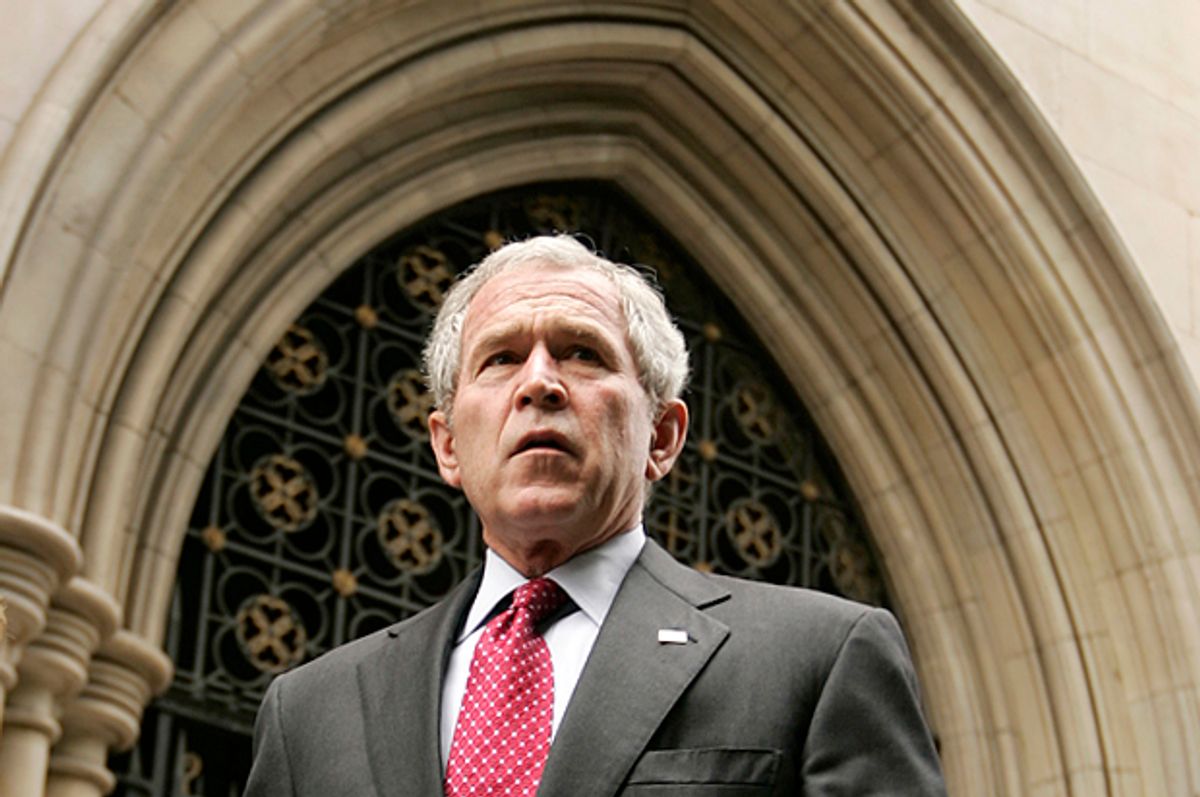

Many politicians, however, have gone farther by advancing specific claims about America’s religious past and its significance for the present. At times, Reagan embraced a fuller notion of the myth. In a 1984 prayer breakfast, he declared that “faith and religion play a critical role in the political life of our nation,” asserting that the Founders had affirmed this relationship. “Those who created our country,” Reagan remarked, “understood that there is a divine order which transcends the human order.” The Founders viewed the government as “a form of moral order,” which found its basis in religion. Reagan was not alone among politicians on the conservative spectrum. In May 2010, former Republican vice presidential candidate and Alaska governor Sarah Palin declared on Fox News that people should “[g]o back to what our founders and our founding documents meant. They’re quite clear that we would create law based on the God of the Bible and the Ten Commandments. It’s pretty simple.” And no modern politician drew more allusions to the nation’s religious heritage than did George W. Bush. A conservative evangelical, Bush frequently revealed his belief in America’s Christian origins, once affirming that “[o]ur country was founded by men and women who realized their dependence on God and were humbled by His providence and grace.” The Founders did more than simply acknowledge their obligation toward God, however; for Bush, America was specially chosen, “not because we consider ourselves a chosen nation” but because “God moves and chooses [us] as He wills.” For Bush, this history had practical applications for present policies, legitimizing his enlistment of religious organizations to operate government-funded social service programs from a “faith perspective” (i.e., the “Faith-Based Initiative”). It also supported an active religious (i.e., Christian) voice in the public realm: “The faith of our Founding Fathers established the precedent that prayers and national days of prayer are an honored part of our American way of life,” Bush insisted. As historian Richard T. Hughes has written about Bush, in his embrace of the myth, Bush “thoroughly confused the Christian view of reality with the purposes of the United States.”

Such rhetoric usually receives a pass from the mainstream press, perhaps because of its ubiquity. On occasion, the press criticizes a politician for too closely associating the nation’s history and goals with God’s purpose, but reporters usually consider such statements as being off-limits for critique. Possibly, this is because there is a long history of public officials from both political parties aligning the national will with God’s plan. Democrat Woodrow Wilson, our most evangelical president between Rutherford B. Hayes and Jimmy Carter, once said, “America was born a Christian nation. America was born to exemplify that devotion to the elements of righteousness which are derived from the revelations of Holy Scripture.” And the nation’s most beloved president, Abraham Lincoln, regularly averred that the nation was subject to God’s will, and to his judgment. Still, not all religious allusions have been the same. Lincoln’s religious rhetoric was often in the form of a jeremiad, calling the nation to a moral accountability. Lincoln was careful not to align God with the Union side during the Civil War, noting in his Second Inaugural Address that both sides “read the same Bible and pray[ed] to the same God [while] invok[ing] His aid against the other.” And Jimmy Carter, a devout Southern Baptist, also drew a line between supplicating God’s blessings and sanctifying the nation. Despite the nuanced rhetoric of some of our political leaders, religious declarations by politicians perpetuate the impression that America was specially ordained by God and that the nation’s governing documents and institutions reflect Christian values.

The resiliency of a belief in America’s religious origins, particularly of its “chosen” status, is, in part, perplexing. American religious exceptionalism has not been taught in the nation’s public schools since the mid-1900s, though the theme was common in school curricula, either explicitly or implicitly, for the first 150 years of public schooling. Yet the narrative persists, much of it from a religious or patriotic perspective, fueled by popular literature and the media and promoted by evangelical pastors and conservative politicians and commentators.

One explanation for the popularity of this account is that the idea of America’s religious founding has a protean, chameleon-like quality. For many people, the concept may mean little more than that America was settled in part by religious dissenters who helped establish a regime of religious liberty unmatched in the world at that time. For a related group, it is the belief that religious perspectives and values pervaded the colonial and revolutionary periods, and that the Founders—however they are defined—relied on those values, among others, in constructing the ideological basis for republican government. Closely associated with this last understanding is the sense that people of the founding generation were at ease with public acknowledgments of and support for religion, and that the Founders believed that moral virtue was indispensable for the nation’s well-being. A majority of Americans likely hold the above views to one degree or another. And all of these perspectives find degrees of support in the historical record. The above views, however, do not necessarily involve claims that America was specially chosen by God in the model of Old Testament Israel or that promote a form of religious exceptionalism, that is, a belief in the unique status and mission of the United States in the world. The embrace of religious exceptionalism represents the chief ideological break between the above perspectives and the remainder.

The next view, in level of intensity, shares much in common with the last perspective but elevates the role of religion from being one of many ideologies informing the founding era to a status of prominence. It argues that religion—frequently defined as Calvinism—was the chief energizing propulsion of the founding ideology and that the American democratic system cannot be understood without appreciating its Christian roots. This perspective often emphasizes the religious piety of the Founders and their generation, disputing claims that a majority of the early leaders were religious rationalists or that the populace was generally non-churchgoing. The final perspective that can be distinguished under this broad taxonomy includes an additional claim of a divine intervention in the nation’s creation—that America was an especially chosen nation and that the Founders acted as they did due to God’s providential guiding hand. Under this last perspective, the nation’s past and founding documents assume an almost sacred quality. As can be appreciated, due to the variety of potential understandings and fluidity between perspectives, it can be difficult to decipher what one means when speaking of America’s Christian heritage or of it being a “Christian nation.” A vague assertion is likely to resonate with a large number of people.

Still, a distinctive argument about America’s religious foundings, one that encompasses the last two perspectives, has emerged in recent years, finding an audience among religious and political conservatives. Ever since the nation’s bicentennial, conservatives have raised claims about America’s Christian heritage in their efforts to gain the moral (and political) high ground in the ongoing culture wars. These arguments take on several forms, from asserting that the Founders relied on a pervasive Calvinist ideology when crafting notions of republicanism to claiming that the Founders were devout Christians and were guided in their actions by divine providence. As evidence, proponents point to public statements and official actions during the founding period—for example, thanksgiving day proclamations—that purportedly demonstrate a reliance on religious principles in the ordering of the nation’s political and legal institutions. A plethora of books have been published that attest to the Founders’ religious piety and to their belief about the role of religion in civil government. Although these books are usually weak on historical scholarship, they project a degree of authority by frequently “disclosing” previously “unknown” historical data, purposely ignored (allegedly) by professional historians. The common theme, as expressed by popular evangelical author Tim LaHaye (of the Left Behind series), is that an orthodox “Christian consensus” existed at the time of the founding and that the Founders intended to incorporate Judeo-Christian principles into the founding documents. As another writer summarizes the claim:

The history of America’s laws, its constitutional system, the reason for the American Revolution, or the basis of its guiding political philosophy cannot accurately be discussed without reference to its biblical roots.

Connected to this central theme is a second common claim: that scholars, judges, and the liberal elite have censored America’s Christian past in a conspiracy to install a regime of secularism. Public school textbooks and college history courses generally avoid references to America’s religious heritage, creating the impression in the minds of students that that past did not exist. LaHaye calls this omission a “deliberate rape of history,” asserting that “[t]he removal of religion as history from our schoolbooks betrays the intellectual dishonesty of secular humanist educators and reveals their blind hostility to Christianity.” This account is promoted in textbooks published for private evangelical schools and Christian homeschoolers, with the popular God and Government asserting that there is “a staggering amount of religious source material that shows the United States of America was founded as a Christian nation.” But tragically, “[f ]or generations the true story of America’s faith has been obscured by those who deny the providential work of God in history.”

Likely no person has written more about America’s Christian past, or has done more to promote ideas of a distinct Christian nationhood, than David Barton, a self-taught “historian” who is the darling of conservative politicians such as Newt Gingrich, Mike Huckabee, and Glenn Beck. Barton asserts that “virtually every one of the fifty-five Founding Fathers who framed the Constitution were members of orthodox Christian churches and that many were outspoken evangelicals.” According to Barton, these men believed that God intervened directly in the founding process and intended for Christian principles to be integrated into the operations of government. Even though scholars overwhelmingly criticize his writings, particularly his methodology of cherry-picking quotations of leading figures, Barton’s interpretation commands a large following. Religious and political conservatives, predisposed to distrust the liberal academy, remain impressed by Barton’s massive collection of historical documents demonstrating a “Christian consensus” at the founding.

One scholar sums up this overall phenomenon:

The number of contemporary authors on the quest for a Christian America is legion. The Christian America concept moves beyond a simple and fundamental acknowledgement of Christianity’s significance in American history to a belief that the United States was established as a decidedly Christian nation. Driven by the belief that separation of church and state is a myth foisted upon the American people by secular courts and scholars, defenders of Christian America historiography claim they are merely recovering accurate American history from revisionist historians conspiring to expunge any remnant of Christianity from America’s past.

In characterizing the issue in such dire terms for people of faith, it is little wonder that the claim of America’s special religious past continues to resonate.

To a degree, these proponents—I will term them “religionists”—are not tilting at imaginary windmills. For more than sixty years the dominant legal interpretation of the nation’s constitutional founding was that the Founders intended to establish a “high wall of separation between church and state,” as Supreme Court Justice Hugo Black declared in 1947. The model was Thomas Jefferson’s metaphorical Wall, and its scripture was James Madison’s Memorial and Remonstrance, not those annoyingly contrary actions like the First Congress’s appointment of a chaplain in 1789. The high point—or low point, depending on one’s perspective—came in 1962 and 1963, when the Supreme Court struck down nonsectarian prayer and Bible reading in the nation’s schools, practices that had extended back to the beginnings of American public education and that were viewed by many as affirming the nation’s gratitude to a beneficent God. Even though the high court never held that public schools could not teach about the nation’s religious heritage if done from an academic perspective, rather than from a devotional one—with the Court going out of its way to reaffirm that a “[child’s] education is not complete without a study of comparative religion or the history of religion and its relationship to the advancement of civilization”—most curriculum planners avoided addressing this contentious subject. For many religious conservatives, the Supreme Court’s embrace of a secular-oriented jurisprudence of church-state separation was unsettling and went against their understandings about the nation’s religious heritage.

Religionists have also rightly perceived hostility to Christian nation claims from the secular academy. For years, the scholarly historical canon maintained that the Founders relied chiefly on rational Enlightenment norms, not religious ones, when fashioning the nation’s governing principles. Lawyer and historian Leo Pfeffer led the way for the “secularist” interpretation in the 1950 and 1960s, to be followed by scholars such as Leonard Levy, Gordon Wood, Jon Butler, Frank Lambert, Geoffrey Stone, and Isaac Kramnick and R. Lawrence Moore in their popular book, The Godless Constitution. While these scholars acknowledge the importance of religious thought and movements during the revolutionary period, they see a variety of ideological impulses that influenced the founding generation. Still, most scholars vigorously dispute religionist claims about the “centrality of religious ideas” behind the Revolution, of the “fact of a substantial spiritual dimension to our founding,” or that “Revolutionary-era political thought was, above all, Protestant inspired.”

A third position has emerged recently in this debate, one that could be termed an “accommodationist” approach. This movement has been led chiefly—though not entirely—by scholars with conservative religious or political leanings. Their scholarship has sought to document the diversity in religious sentiment, particularly forms of Protestant orthodoxy, among members of the founding generation, including those within the political leadership. In addition, accommodationists have worked to expand the pool of influential Founders, arguing that the church-state views of icons Thomas Jefferson and James Madison “are among the least representative of the founders.” They criticize the accepted canon as a “selective approach to history” that “distort[s] . . . the founders’ collective views on religion, religious liberty, and church state relations.” The book titles promoting this interpretation are revealing: The Forgotten Founders on Religion and Public Life; and Forgotten Features of the Founding. Like religionist writers, this perspective frequently emphasizes the Founders’ personal religious piety and their commitment to a public virtue. It asserts that the Founders could be both professing Christians and political rationalists and committed to a moderate scheme of church-state separation. These scholars frequently side with the religionists regarding the Founders’ belief in divine providence and their reliance on “higher” norms when conceptualizing legal rights and liberties. In contrast, accommodationists generally agree with secularist scholars about the variety of ideological impulses that informed the founding period, although they usually place more weight on religious statements and actions by the Founders. This latter emphasis means that accommodationist scholars are closer to religionists in asserting the primacy of religious thought during the founding period. While this effort to expand on the diversity of thought during the founding period is commendable, it often becomes blurred by corresponding efforts to marginalize the impact of leading Founders who held heterodox religious views (e.g., Thomas Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin).

While most, though not all, accommodationist scholars are not agenda driven, their conclusions often confirm the claims of Christian nationalists like LaHaye and Barton. In particular, the religionist position has drawn support from conservative legal scholars who have criticized the Supreme Court’s “separationist” interpretation of church-state relations, particularly the Stone-Warren-Burger Courts’ reliance on the writings of Jefferson and Madison. As one leading scholar, Harold Berman, writing in the mid-1980s, maintained:

[Prior to the 1940s] America professed itself to be a Christian country. Even two generations ago, if one asked Americans where our Constitution—or, indeed, our whole concept of law—came from, on what it was ultimately based, the overwhelming majority would have said, “the Ten Commandments,” or “the Bible,” or perhaps “the law of God.”

Berman bemoaned that since that time, America’s public philosophy had “shifted radically from a religious to a secular theory of law, from a moral to a political or instrumental theory, and from a communitarian to an individualistic theory.” A decade later, Yale law professor Stephen Carter charged in his missive, The Culture of Disbelief, that there was a pervasive disregard of faith in the popular culture, one that was perpetuated by a secular-leaning elite. Other scholars with evangelical leanings have more willingly embraced parts of the religionist argument—chiefly that religion was a leading factor inspiring and motivating the Founders—thus validating major claims of the popular religionist writers.

This renewed attention to the nation’s Christian foundings has not gone unnoticed by sympathetic politicians and officials, such as the members of the Texas State Board of Education, and conservative judges such as William Rehnquist, Antonin Scalia, and Clarence Thomas. This narrative has impacted the content of social science curriculum in Texas schools and the judicial interpretation of First Amendment jurisprudence. Justices have cited the nation’s religious heritage in upholding legislative prayers and displays of Christian crosses and the Ten Commandments on government property. During the Cold War, the justices once declared that “[w]e are a religious people whose institutions presuppose a Supreme Being.” Conservative justices have dusted off that statement, while adding “that the Founding Fathers believed devoutly that there was a God and that the unalienable rights of man were rooted in Him is clearly evidenced in their writings, from the Mayflower Compact to the Constitution itself.” Religion, Chief Justice Rehnquist concluded, “has been closely identified with our history and government.” Armed with this historical ammunition, religious and legal conservatives give notice that the accepted interpretation of the nation’s non-religious founding is contestable territory.

Excerpted from "Inventing a Christian America: The Myth of the Religious Founding" by Steven K. Green. Published by Oxford University Press. Copyright 2015 by Steven K. Green. Reprinted with permission of the publisher. All rights reserved.

Shares