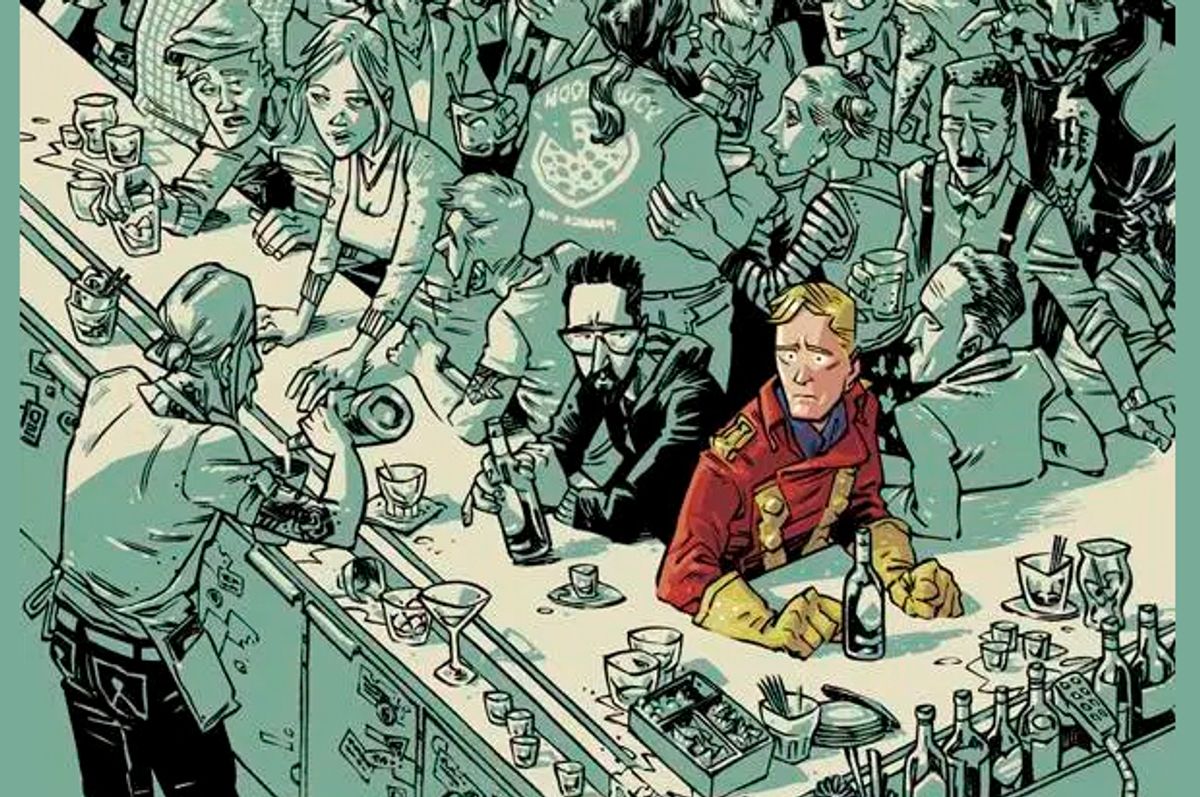

Image's "Airboy" is the semi-autobiographical account of author James Robinson's descent into drug and alcohol addiction. He's been pigeonholed as a writer who resurrects the work of comics' Golden Age, and so it should come as no surprise that his protagonist is a self-loathing, sexually exploitative asshole of no small regard. But in the second issue, that loathing reverses course, targeting the people around James Robinson -- in this case, a group of "trannies and drag queens" -- instead of the subject who is its source.

It's not simply that Robinson (the character) uses a derogatory term for a trans woman that's at issue here -- it's that Robinson the author uses trans women as a means of punishing the character. As The Rainbow Hub's Emma Houxbois wrote, Robinson "degraded trans women by portraying us both as sex objects and a carnival sideshow to be gawked at."

"To what end?" she continued. "To use us as a symbol of the fall of western civilization to drive Airboy into a furious rage? To give Robinson the world weary asshole street cred he’s so desperate to peddle as an excuse for not having anything interesting to say? There’s no voice, no agency, no humanity to any of the trans women in this comic. Just an open mouth to fuck or a penis to gawk at."

Not content with merely critiquing the book's content, Houxbois contacted Graphic Policy's Elana Levin and Brett Schenker -- who also wrote a blistering critique of the issue in which they outlined why it's problematic to depict trans women's sexual default as the attempt to "trick straight men" into having sex with them -- and together they contacted the LBGTQ advocacy group GLAAD, which promptly issued a statement in which they expressed their particular disappointment with author Robinson, whose "previous work on 'Starman' and 'Earth 2' included multi-dimensional gay male characters [and] received GLAAD Media Award nominations for Outstanding Comic Book."

The very next day, Robinson reached out to GLAAD and sent a detailed apology which -- while not perfect -- can't be faulted for its sincerity.

"Often public figures just issue a quick apology, a snippet of contrition, in the hope that the light of scorn will then shine away from them," he wrote. "But those apologies often feel inauthentic or meaningless, and I didn't want to do that."

"It’s a sad and terrible fact that the transgender community is one that is often misunderstood and mocked. And that honestly, truly, breaks my heart," Robinson continued. "It is a beautiful community full of shining souls, which in a different work on a different day I would proudly show in all its variety and wonder."

"And yet here I am, in my eagerness to create a scenario that mocks my own moral worthlessness, I do no better than the worst kind of person, blindly marking the transgender community with the same sullying brush I chose to paint myself -- instead of giving it the dignity and respect it deserves and is so very often denied."

Robinson concluded by acknowledging that he took "minor solace -- very minor" in the fact that Houxbois and Levin started a conversation -- even though the conversation they initiated was highly critical of him. "The discourse I'm seeing on-line about this," he wrote, "is open, healthy and ultimately a good thing."

Considering that this is an industry in which, as Graphic Policy's Schenker so succinctly charted, fans are demonstrably more concerned with the seating arrangement at Comic-Con than the representation of members of the LGBQT community in comic books, this controversy can only be characterized as an unqualified success.

Especially given the fact that the artist of "Airboy," Greg Hinkle, not only thanked activists like Houxbois, Levin and Schenker for bringing the problem to his attention, but also offered to continue the conversation at Comic-Con itself -- and that conversation did, in fact, continue. Both the specific issue of "Airboy" and the reaction to it were discussed at length in the panel on comics journalism, which can be listened to here. This is a distinctly pleasant turn of events in an industry which, more often than not, leaves progressives saying "This is why we can't have nice things."

Shares