Americans generally feel that the GOP is the party of the rich, so it's no surprise the GOP base would embrace celebrity billionaire Donald Trump as “one of us.” Or that the “serious candidate” Jeb Bush carelessly complained about lazy American workers in early July, saying that “people need to work longer hours.” The ensuing outcry led to a swift cleanup effort—Bush was only talking about the part-time employed, we were told. But that claim rang more than a bit hollow on two counts.

First, as Paul Krugman pointed out, this blame-the-lazy-workers attitude was much more widespread within the GOP than among Democrats—from Romney's 47 percent remark to Republican attacks on unemployment benefits and food stamps to Rand Paul's claims those claiming disability benefits are malingerers. Worshiping the rich and despising the less fortunate are two sides of the same (bit)coin.

Second, Bush's supposed concern for the part-time employed was deeply at odds with actual GOP policies which make life especially hard for workers on the bottom, including widespread union-busting which over the decades has helped create so many part-time jobs in the first place. Indeed, within days of his snafu, Bush himself expressed opposition to the Obama administration's expansion of overtime pay protection for nearly 5 million workers not currently covered.

Despite their supposed diversity, GOP candidates share a dependence on two broad-spectrum lies: First, that they're better at producing overall growth -- for example: Trump boasting, “I will be the greatest jobs president that God ever created,” or Bush promising “4 percent growth as far as the eye can see” -- and, second, that growth by itself will benefit everyone. Democrats, in contrast, can win by focusing on specific truths—the nitty-gritty policies they will implement to materially improve people's lives, that Republicans either bitterly oppose or at best seem indifferent to. One reason that Bernie Sanders has been doing so well is precisely because he's been focusing on such issues for decades -- and also, crucially, knows how to build a broader vision based on those specifics.

A quick note about those two broad Republican lies: In reality, Democrats are much better than Republicans for the economy, as shown by more than a dozen studies discussed by Eric Zeusse in his 2012 book, "They're Not Even Close: The Democratic vs. Republican Economic Records, 1910-2010." (The less said specifically about the Bush family record, particularly on job creation —less than 4 million in 12 years—the better.) As for the second lie, overall growth stopped helping most Americans back in the 1970s, when the GOP's neoliberal “trickle down” economics began replacing the social democratic policies, from the New Deal to the Great Society, which had produced decades of shared prosperity.

From 1948 to 1972, the average incomes of the top 10 percent and bottom 90 percent rose by 84.2 percent and 96.3 percent, respectively; but from 1973 to 2008, the top 10 percent's average incomes rose another 74.45 percent, while the bottom 90 percent's average incomes fell 12.45 percent. Even the bottom 99 percent's average incomes only rose a minute 0.12 percent annually over this time, about one-thirtieth of the annual 3.51 percent increase for the top 1 percent.

Debunking lies is not how elections are won, however. Much more important is promoting contrasting truths, putting the other side on the defensive, and here's where the details wrapped up in those lies can really start to matter. As labor economist John Schmitt has argued, inequality fell as a result of social movements from the 1920s to the 1970s, and grew as a result of an organized elite backlash against them in subsequent decades. In a 2009 paper, “Inequality as policy: The United States since 1979,” Schmitt identified the equalizing movements -- “labor, civil rights, feminist, environmental, and consumer” -- and noted that employers had initially resisted them, but eventually made peace with them, while still opposing the legislation enshrining their gains. Then, from the mid-'70s onward, they began rolling back those legislative gains via a series of policies that were “sold as ways to enhance national efficiency,” including de-unionization, deregulation, privatization, “free-trade” agreements, and a declining minimum wage.

“I am not simply arguing that the explosion of inequality was a side-effect of these policies.” Schmitt explained. “I am arguing, rather, that the explosion of inequality – what is, effectively, the upward redistribution of the large majority of the benefits of economic growth since the late 1970s – was the purpose of these policies. The purported efficiency gains, which were realized in some cases but not in others, were merely a political distraction.”

As Schmitt points out here, and elsewhere, it's not just a matter of wage inequality. American workers have many fewer protections than their counterparts in other advanced industrial democracies. In a January 2015 paper, “Failing on Two Fronts: The U.S. Labor Market Since 2000,” he pointed to three objective comparisons to make this point. First, an OECD measure of labor protections (advance notice, severance pay, reason for dismall, etc.) shows Germany at 2.9, France at 2.4 and 10 other European countries above 2, with the U.S. alone at the bottom at 0.3, one third the next lowest country, Canada. Second, comparing the generosity of unemployment insurance, workers in Germany and France receive 72 percent and 71 percent of their regular pay, and 11 other countries receive between 66 percent and 82 percent, compared to just 53 percent in the U.S. Finally, the percentage of workers covered by collective bargaining is 61 percent in Germany, and 92 percent in France, with 11 other countries from 61 percent to 99 percent, while the US is in last place, at 13 percent. The U.S. is also an outlier on vacation time -- the only advanced economy without paid vacation -- and on paid sick leave -- also alone in providing none.

The “efficiency” measures Schmitt criticizes vary significantly in how contested they are, and by whom. For example, Obama recently energetically twisted arms to get fast-track authority for more “free trade” agreements, and it's an issue where Hillary Clinton's ambiguity stands in contrast to Bernie Sanders' stark opposition. But thanks to the Occupy Movement and its offshoots, such as the Fight for 15, there's a growing range of such issues on which majority pressure is finding an increasingly unified expression of Democratic support, even as Republicans remain staunchly opposed. The more attention is focused on these specific issues, the better off all of us will be.

(1) Raising the minimum wage. The most salient such issue so far has been the minimum wage, which a broad range of GOP politicians now openly oppose raising—even though voters in five states voted to raise the it last November, in the same election that handed Republicans control of the U.S. Senate. According to a 2012 issue brief by Schmitt, the minimum wage closely tracked wage and productivity growth during the post-WWII era through about 1970, but that hasn't been the case ever since. "By all of the most commonly used benchmarks – inflation, average wages, and productivity – the minimum wage is now far below its historical level," Schmitt writes. "By all of these benchmarks, the value of the minimum wage peaked in 1968." Let's look at each of those three bench marks:

- Inflation: If the minimum wage had kept pace with inflation (as measured by the Consumer Price Index) since 1968, the 2012 minimum wage would have been $10.52.

- Average wages: The federal minimum was close to 50 percent of the average production worker earnings throughout much of the 1960s, peaking at 53 percent in 1968. If it were at that same 50 percent figure today, the federal minimum would be $10.01 per hour.

- Productivity: Finally, if the minimum wage had continued to increase with average productivity growth since 1968, it would have reached $21.72 per hour in 2012.

So, any way you cut it, today's federal minimum wage -- $7.25 per hour -- is ridiculously low.

As a result, a vigorous grassroots campaign to raise the minimum wage, both in specific industries and through local, state and federal legislation, has taken hold over the past several years, and has begun to bear fruit. Seattle, San Francisco and Los Angeles all have raised their minimum wages to $15 per hour, over a period of years. Meanwhile, a poll this past January conducted by Hart Research Associates, found that 75 percent of Americans – including 53 percent of Republicans – support a federal minimum wage increase to $12.50 by 2020; the same poll also found that 63 percent of Americans support an increase to $15.00.

In the face of all these facts, and this broad support, GOP politicians remain strikingly hostile and out-of-step. One favorite point they often try to hang onto is the claim that raising the minimum wage may cost jobs -- “That's how it's always worked,” Bush rationalizes -- so fighting the minimum wage is their way of looking out for the little guy!

However, while a minimum-wage hike could hypothetically become a real problem in the extreme -- a minimum wage of $500 per hour, for example -- the same cannot be said about the actual range of minimum wage proposals being considered. In fact, there's reason to believe that the exact opposite is true, that increased wage earnings increase demand (because consumers have more money to spend) and hence the need for more employment (in order for businesses to meet the greater demand for products and services). Higher pay also reduces turnover, promotes skill development and employee loyalty.

In 1993, a groundbreaking case study by David Card and Alan Krueger actually found employment gains after a minimum wage hike, and similar findings have been replicated throughout the 20-plus years since (overview here). So, surprise, surprise, the GOP hostility to the minimum wage is built on faith-based lies—just like voter fraud and Iraq's WMDs -- and on assumptions of morality: that those with money deserve to have more of it, and those without deserve to have even less. The belief that higher wages don't help struggling workers is a core belief of GOP economics—and it spells doom for them if it becomes too central in the 2016 election cycle.

(2) Raising overtime pay. Republicans are also opposed to expanding overtime pay, which Obama is already taking action on, as noted above. Overtime pay is based on the same law as the minimum wage, the 1938 Fair Labor Standards Act.

As explained on White House website, overtime rules “apply to most hourly and salaried workers, with exceptions including one for executive, administrative, and professional workers. In 1975, 62 percent of full-time salaried workers, including a majority of college graduates, were eligible for overtime pay.” But the salary threshold for eligibility hasn't kept up with inflation; it has only been adjusted twice in 40 years, meaning that millions who would have been covered in the 1970s are now not covered. “Today, the salary threshold remains at $23,660 ($455 per week), which is below the poverty threshold for a family of four, and only 8 percent of full-time salaried workers fall below it.” Workers above that threshold can be denied overtime even if they spend a sliver of their worktime on “professional, executive, or administrative” activities. That's how a fast food assistant manager can actually end up working for less than the minimum wage.

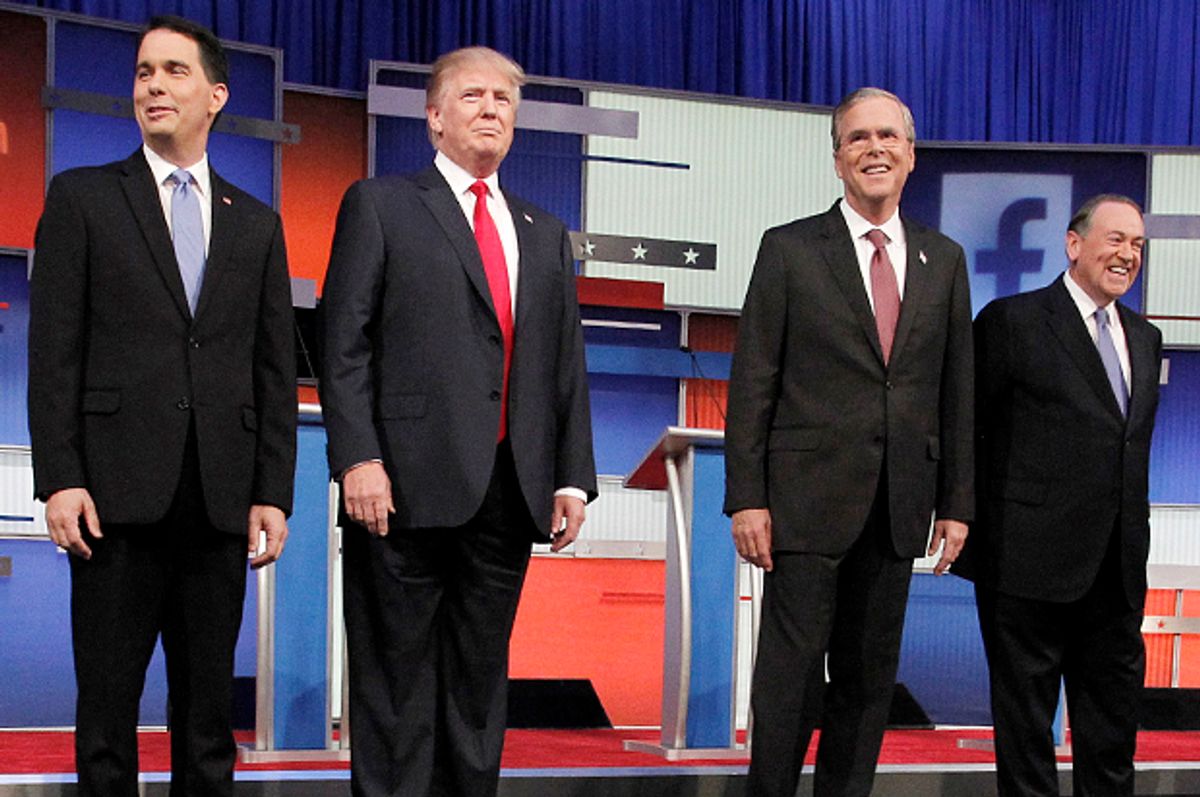

Naturally, Republicans were not in favor of more money for ordinary Americans. But they couldn't come right out and say that. They had to revert to their tried-and-true rationale: giving more money to folks only makes them richer if they are already rich. Hence, Scott Walker said of the president's plan, “The president's effort is a political pitch but the reality is this will lead to lower base pay and benefits and will cut workers' hours and flexibility in the workplace.” And Rick Perry added, “President Obama’s overtime-pay mandate is filled with job-killing incentives that will drastically increase the cost of hiring new workers. Government shouldn’t be in the business of mandating how much employers pay, or the level of benefits they provide."

But Jeb Bush drew the most attention with his protestations. “It’s this prescribed top-down approach that is the wrong approach,” Bush remarked. “The net effects of the overtime rule will be, if history is any guide, there will be less overtime paid, less wages earned.”

However, as a report in The Guardian noted, “Numerous economists attacked Bush’s statement, calling him woefully misinformed." Even opponents of the rule thought Bush's remarks were off-base:

Daniel Hamermesh, a University of Texas labor economist, said: “He’s just 100% wrong,” adding that “there will be more overtime pay and more total earnings” and “there’s a huge amount of evidence employers will use more workers”.

Indeed, a Goldman Sachs study estimated that employers would hire 120,000 more workers in response to Obama’s overtime changes. And a similar study commissioned by the National Retail Federation – a fierce opponent of the proposed overtime rules – estimated that as a result of the new salary threshold, employers in the restaurant and retail industries would hire 117,500 new part-time workers

But perhaps what I found most interesting in all this was Perry's outright statement -- which others merely implied -- that the government had no role in setting rules for how much people get paid.

Taken to its logical extreme, of course, this amounts to a tacit endorsement of slavery. But there's a much more common problem today that this attitude would say shouldn't be solved: the problem of wage theft, which we turn to next.

(3) Cracking down on wage theft. There are a lot of businessmen who agree that government should have no role in telling them how much to pay their workers. A 2009 report, “Broken Laws, Unprotected Workers” found that wage theft affecting the bottom 15 percent of the workforce was so widespread that workers in just three cities -- Los Angeles, Chicago and New York City -- had roughly $2.9 billion in wages stolen from them in 2008. That's as much as all the “normally” reported property theft in California, which has almost twice the population. It was, in short, an invisible crime wave. That report represented a turning point; by quantifying the problem, it became possible to gain political attention, step up existing enforcement mechanisms and begin developing new ones. Mostly this has involved state or local action, with San Francisco passing a model new ordinance, and the city of Los Angeles is poised to follow suit.

In late July, the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors voted unanimously to gather information for a similar county-wide effort. This happened in the same meeting where two Republican members broke with the three Democrats over raising the minimum wage—an indication of how differently the issue is seen. Visibility remains a major concern—at least so far. But hat could be poised to change.

Victor Narro, a project director of UCLA Davis Center, testified about the extent of the problem:

"The UCLA Labor Center published an extensive survey in which we found in any workweek, 8 in 10 low wage workers in Los Angeles, about 655,000 total, suffered from wage theft; 80 percent of these workers work overtime are not properly compensated; another 80 percent of these workers are denied their right to meal and rest breaks. All this amounts to $26.2 million per week stolen from workers in wage theft violations, which is estimated at $1.4 billion a year. Individually these workers lose $2,000 annually out of an average earning of $16,500. which means that's more than 10 percent of their earnings are lost in wage theft."

That's a huge loss of pay—and a strong reminder of just how foolish it would be to leave minimum wage questions to individual employers, as many GOP politicians (Bush, Rubio, Walker) seemingly want to do.

Even though both Republicans on the board voted to move forward, one of them, Mike Antonovich, raised the question of cost—whether the county could afford to take on the effort of fighting wage theft. But Narro also pointed out that it cost the county dearly not to fight wage theft. “Every year we estimate wage theft robs the state and local government between $103 and $153 million in lost tax revenues. $11.7 to $25.5 million of which is lost to the County of Los Angeles,” Narro said.

Narro also pointed out how wage theft and the minimum wage are interrelated issues, practically. “It's important to understand enforcing that wage is just as important as raising it,” Narro said. “All 10 municipalities in California have raised their minimum wage have authorized and funded enforcement of the wage theft.” Fighting wage theft and raising the minimum wage are intimately connected—but many GOP candidates think government should play no role at all.

(4) Reversing de-unionization, and restoring the norm of fulltime, long-term employment.

Wage theft is also intimately connected with three other trends that Republicans all support, which have eroded workers' standard of living: the elimination of full-time career positions, the use of contracting to strip workers of benefits and protections, and the elimination of unions. The connection between these three issues was underscored in the same Los Angeles supervisor's meeting, via the testimony of two workers at port transportation companies -- both victims of wage theft, under the cover of an illegal industry-wide practice of misclassifying workers as “independent contractors.” One, Carlos Quintero, was owed over $200,000 in stolen wages.

(A 2014 report, The Big Rig Overhaul, estimated total wage theft liabilities for port drivers in California at $787 to $998 million annually, based on cases already settled.)

The larger framework for understanding these workers' plight can be found in the 2009 Demos report "Port Trucking Down the Low Road: A Sad Story of Deregulation," by David Bensman.

In the preface of the first report, Demos Senior Fellow Robert Kuttner wrote:

"As industry after industry was deregulated in the late 1970s and 1980s, the promise was of more competition, more innovation and more consumer choice. But as the Dēmos series of reports on deregulation documents, often the most significant impact is on the quality and reliability of work. Often the cost savings are mainly in the form of reduced wages and employee benefits. And the innovations sometimes actually result in a less attractive or reliable product from the perspective of the consumer. The impact on the industry as a whole is characteristically greater instability. This is the case in industries as diverse as electricity, airlines, finance, and trucking."

This summarizes a good deal of what's wrong with the neoliberal economic model, and helps explain why it's no accident that economic growth has become so badly decoupled from wage growth for the vast majority of Americans.

Unions, representing the organized power of workers, are a prime target of this process.

Combating the abuses of contracting and restoring the norm of fulltime, long-term employment are vitally important issues in their own right, but union power represents a crucial variable affecting the entire framework of power relations in which these other battles take place, which is why its worth focusing directly on the relationship between union power and broad prosperity.

A static, one-time state-level comparison showing this relationship was published by Richard Florida in the Atlantic in 2011: “Unions and State Economies: Don't Believe the Hype.” His main findings were summarized in the sub-head: “Unionization levels correlate with not only higher hourly wages but higher income levels across the board.”

Florida expands on the point here:

“To put it baldly, unions are associated with the country's economic winners, not its losers.... States with higher levels of union membership work less hours per week but make more money.”

He did not find any impact of unionization on inequality. But comparisons over time do show such a relationship quite clearly. This was vividly demonstrated by Colin Gordon, Professor of History at the University of Iowa and a Senior Research Consultant at the Iowa Policy Project in a 2012 blog post for the Economic Policy Institute, "Union decline and rising inequality in two charts." First, Gordon called attention to the strong decades-long inverse correlation between union density in America and the income share of the richest 10 percent of Americans. They are almost mirror images, stretching all the way back to the 1920s. His second chart showed how the state-level relationship between union density and inequality had changed over time, from 1979 to 2009, which showed a clear pattern of the inverse relationship there as well.

In his introductory commentary, Gordon wrote:

[T]he basic logic of the postwar accord was clear: Into the early 1970s, both median compensation and labor productivity roughly doubled. Labor unions both sustained prosperity, and ensured that it was shared.... The wage effect alone underestimates the union contribution to shared prosperity. Unions at midcentury also exerted considerable political clout, sustaining other political and economic choices (minimum wage, job-based health benefits, Social Security, high marginal tax rates, etc.) that dampened inequality. And unions not only raise the wage floor but can also lower the ceiling; union bargaining power has been shown to moderate the compensation of executives at unionized firms.

Over the second 30 years post-WWII—an era highlighted by an impasse over labor law reform in 1978, the Chrysler bailout in 1979 (which set the template for “too big to fail” corporate rescues built around deep concessions by workers), and the Reagan administration’s determination to “zap labor” into submission—labor’s bargaining power collapsed.

In short, unions make life better for society as a whole. Their decline makes life worse. It's a fundamental fact of life that's worth repeating over and over again. The fact that Republicans are so deeply hostile to unions is a clear indication of how little they really care about the vast majority of the American people.

But it's also worthwhile fighting to expand the sorts of benefits that unions in other countries have helped provide. In particular, it's worth returning to two already mentioned which are worth making issues of in the short run—paid sick days and paid vacations. They're the last two specifics for us to consider.

(5) Paid sick leave. After President Obama called for paid parental and sick leave in his State of the Union address, the Nation Journal ran a story, “How Paid Sick Leave Emerged as a Democratic Strong Suit: It didn't happen in Washington,” highlighting the fact that it's been a struggle bubbling up from the city and state level for more than decade now. But, as the Hill reported shortly thereafter, “GOP pans push for paid leave”:

“I never thought that emulating the European economic model is good for America,” laughed Rep. Charlie Dent (R-Pa.).

Two months later, when Washington Senator Patty Murray's introduced the “Deficit-Neutral Reserve Fund for Legislation to Allow Americans to Earn Paid Sick Time” as an amendment, 16 Republicans voted for it, a good number of them facing swing-state re-election contests. However, all the senators planning presidential bids -- Cruz, Graham, Paul, and Rubio -- voted against it.

Meanwhile, on July 1, a new California law went into effect, providing three days of paid sick leave annually, including part-time employees. Before California, only Massachusetts, Connecticut, Washington D.C. and 18 city had similar provisions. The tide is definitely turning, and this will certainly be part of the issue mix this election cycle.

(6) Paid vacation. If paid sick leave is a sleeper issue -- off the radar for Beltway elites, but suddenly coming into view -- the struggle for paid vacations is going to take a lot more work. After all, paid sick leave is about responding to need. Paid vacations? That's just too much fun to allow for undeserving working- and middle-class folks. But America's anomalous status is not likely to remain unchallenged forever, particularly since paid vacations can easily be argued for in terms good old “family values.”

As noted in a 2013 report the Center for Economic andPolicy Research “No-Vacation Nation Revisited,” America's lack of paid vacation contrasts sharply with the European Union, where workers are legally guaranteed at least 20 paid vacation days per year, with 25, 30 or even more guaranteed days in some countries.In fact, five countries even mandate a small vacation pay premium to help with vacation-related expenses. The gap grows even larger when paid legal holidays are included; most rich countries provide between 5 and 13 per year, while the U.S. guarantees none.

The fact that paid vacations usually aren't even talked about by politicians is not a situation we should simply accept. It's time to ask why Americans alone aren't good enough to have them. In fact, it's the perfect sort of issue for social media to help raise in the coming election cycle. Want folks to stop tweeting about it? Pay them to go away!

Shares