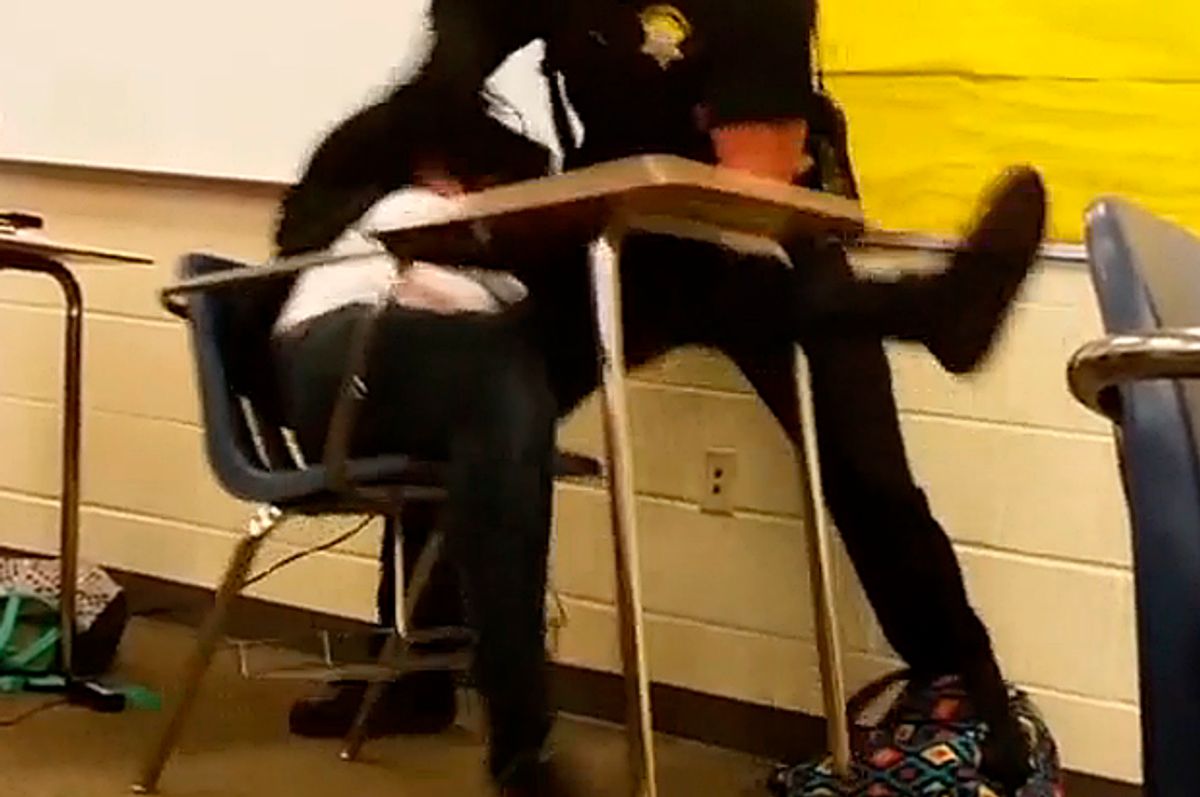

The video of a school police officer in Columbia, South Carolina, brutally flipping a student backward and then heaving her across the room is instructive because it is not an isolated incident.

Earlier this month, ten people were arrested during protests in Pawtucket, RI, following a videotaped incident of a school police officer aggressively taking down a student who did not appear to pose a threat. In August, the ACLU filed a federal lawsuit accusing a school police officer in Covington, KY, of shackling two children with ADHD. The children were only 8 and 9 years old. (A video of one incident is here). In March, the Houston Chronicle reported that "police officers in eight of the largest Houston-area school districts have used force on students and trespassers at least 1,300 times in the last four years."

For poor children of color, the mouth of the school-to-prison pipeline is manned by police officers who have in recent decades proliferated in districts nationwide. The mass deployment of schools cops, commonly referred to as "school resource officers," has been made without careful thought or research. And it has produced horrible outcomes.

"Police officers are being used in school for minor misbehavior," says Aaron Kupchik, a sociologist at the University of Delaware and an expert on school discipline and police. School police officers are justified in the name of preventing serious incidents like shootings, but often end up bringing a law enforcement approach to routine discipline.

"Why was a police officer there to remove a student who wouldn't leave a classroom?" Kupchik asks. "Cases like this will happen when you introduce police into school environments."

Don Bridges, who works as an officer in a Baltimore County high school and serves as the first vice president of the National Association of School Resource Officers, explains that criminal charges and force against students "has to be a last resort," and says that officers need to know that "a school house is different from a beat on the street."

Bridges says to comment on the South Carolina incident in depth without more details. But he calls the video "disturbing."

"The first question we should be asking," he continues, "is what kind of training are [resource officers] getting?" He says that Ben Fields, the officer involved in the South Carolina incident, was not trained by NASRO. The group recently released a statement calling for officers to be prohibited involvement "in formal school discipline situations that are the responsibility of school administrators" and for the use of physical restraints to be limited.

Many school police officers no doubt maintain positive relationships with students and don't commit abuse. But officers' widespread presence in schools is tied up in the larger rise of "zero tolerance" policies in recent decades, resulting in the widespread suspension and expulsion of young people, especially of those of color. The number of secondary school students suspended or expelled increased from one in thirteen in 1972–1973 to one in nine in 2009–2010, according to a forthcoming article in the Washington University Law Review by Jason P. Nance, a professor at the University of Florida Levin College of Law.

What's even more troubling is that a schoolyard fight that would once result in a trip to the principal’s office now often ends in handcuffs.

"We should question whether we need SROs in schools at all," says Nance, in an email. "From a cost-benefit standpoint, the benefits of having SROs in schools, if any, are unclear; yet, the costs are high – they are expensive to hire, they impede school climate in many schools; and SROs are linked to having more students involved in the justice system."

No nationwide data on school-based referrals to law enforcement exists. But data from individual districts cited by Nance shows that such referrals skyrocketed in the early 2000s.

"Twenty-seven states require school officials to refer students to law enforcement for incidents relating to controlled substances," Nance explains. "Fifteen states require referral for incidents involving alcohol. Eight states mandate referral for theft. Eight states for vandalism of school property, and 11 states for robbery without using a weapon."

Alabama's statute, he writes, requires school officials to report to law enforcement any “violent disruptive incidents occurring on school property during school hours or during school activities conducted on or off school property after school hours.” In Illinois, school officials must report “each incident of intimidation."

The saga of Ahmed Mohamed, the science-loving teenage tinkerer arrested in Texas for bringing a homemade clock to school, reportedly began after a teacher contacted a school police officer. The incident raised the issue of Muslims being profiled. It also, however, poses a question about the criminalization of student life more generally: If an officer was not already stationed on campus, would teachers and administrators have been so quick to involve law enforcement?

"I think there are a number of things that could have been done differently in that situation," says Morgan Craven, director of Texas Appleseed's School-to-Prison Pipeline Project, in an email. "It certainly makes sense that if officers are not already physically present in a class or school, the likelihood that they will get involved in a particular incident probably decreases."

The number of school police officers rose to 19,900 in 2003, from approximately 12,300 in 1997, according to Nance. The number appears to have remained steady since, though he says that he is not aware of data more recent than 2007. In the late 1970s, he writes, "there were fewer than one hundred police officers in our public schools."

According to Kupchik, police officers are most prevalent in schools with high numbers of students of color but are also the norm in heavily white high schools as well. School shootings appear to be creating yet more political support to put cops in schools, particularly since the Newtown massacre.

"School shootings did not cause it" says Kupchik, noting that the rise in school police predates the Columbine massacre. "But it did accelerate it and perhaps, even more so, justified it."

Putting an officer in each school in the country, as some advocate, would cost an estimated $3.2 billion, according to Nance.

"It follows along with trends in policing and punishment elsewhere where we rely on police and the justice system to deal with other types of problems," says Kupchik, pointing to the use of law enforcement to deal with drug use. The country as a whole has allowed "the justice system to have a larger role in our lives and welfare, and I think policing in schools is a part of that overall trend."

School districts are spending money on deploying police to remove disruptive kids from class and place them into the criminal justice system. Meanwhile, many segregated districts that serve the most marginalized youth of color remain starved for cash. The severe penalties meted out to "failing" schools in the high-stakes testing era creates another unsavory incentive to remove low-performing children.

Just one arrest can be be extraordinarily harmful.

Nance cites a study by criminologist Gary Sweeten that found "a first-time arrest during high school almost doubles the odds that a student will drop out of school, and a court appearance associated with an arrest nearly quadruples those odds."

According to an empirical analysis conducted by Nance, low-level offenses like "fighting without a weapon, threats without a weapon, theft, and vandalism" are "between 1.38 and 1.83 times" more likely to be referred to law enforcement "in schools that have regular contact with SROs than for schools that do not. For other non-weapon offenses, such as robbery without a weapon, drug offenses, and alcohol offenses, the odds of referral increase by 3.54, 1.91, and 1.79 respectively."

Nance also found that schools with higher rates of serious crime are more likely to refer low-level violations to law enforcement, suggesting that schools have embraced a "broken windows" quality-of-life-offenses approach to discipline. From mandatory drug testing for athletes to warrantless locker searches, schools have in many totally non-hyperbolic senses become police states.

In 1969, the U.S. Supreme Court ruled in Tinker v. Des Moines that students do not "shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate." But other constitutional rights often don't apply.

School officials don't need a warrant to conduct a search, writes Nance, and "may use metal detectors, search through students’ lockers, conduct random sweeps for contraband, and install surveillance cameras in the hallways and public rooms throughout the school." Students don't have a right to a Miranda warning before they are questioned, even if the incident in question may be referred to law enforcement.

Reforms are possible, and activists nationwide have in recent years pushed back at zero-tolerance discipline.

Clayton County, Georgia juvenile court Chief Judge Steve Teske initiated a process to deal with many school discipline issues without making arrests. School-based referrals to juvenile court from 2003 to 2010 fell by more than 70 percent, according to the Washington Post. Last year, the Los Angeles Unified School District announced that school police would cease issuing citations for minor offenses. Citations had already declined from 11,698 in 2009-10 to 3,499 in 2013-2014, according to the LA Times. Last December, the New York Civil Liberties Union announced a settlement with the Syracuse Police Department after two students allege they were tased without cause.

FBI Director James Comey recently lent his credence to the so-called "Ferguson effect," the dubious idea that police being too afraid to enforce the law has caused an uptick in violent crime (an increase in violence that, in reality, appears to be non-existent on a nationwide level). The South Carolina incident is a reminder that for some cops, inside school and on the streets, cameras have't made any difference at all.

Shares