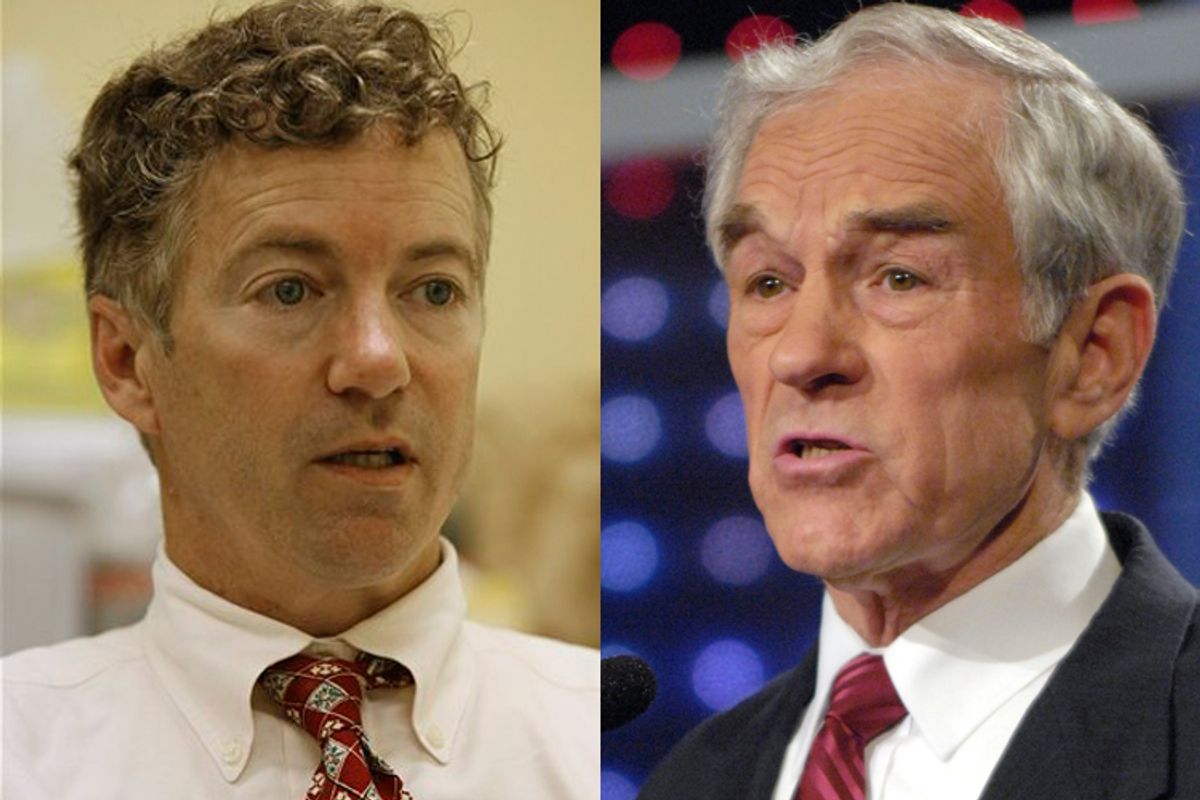

There are a lot of failed presidential campaigns littering the landscape right now, but one in particular represents something more than just one person's failed ambitions. Rand Paul's inability to match his father's performance signals the failure of a conservative re-invention process which once seemed like the hottest thing around.

Conservatives supposedly revere tradition—until they don't. As Salon contributor Corey Robin pointed out in "The Reactionary Mind," the quintessential “gradualist” Burkean conservative, Edmund Burke, became a wild-eyed radical advocate of fundamental change in response to the French Revolution. In fact, conservatism repeatedly shifts ground, reinventing itself to respond to different circumstances, even as it vehemently denies doing so. Barry Goldwater clashed openly with the religious right legions who gained power on Ronald Reagan's coattails. Reagan saved Social Security, granted amnesty to 1.5 million “illegals” and raised taxes 11 times—he'd be labeled a socialist in today's GOP. So it's no surprise that when Bush Jr.'s presidency began to sour, it was time for conservatism to be reinvented once again. Conservatism, you see, can never fail. It can only be failed... by conservatives in name only.

Which is where the Ron/Rand Paul brand comes into the picture. In recent months, it may have failed spectacularly, but properly understood its very failure may help us understand how conservatives more broadly are even now regrouping to try to succeed where the Paul brand has failed.

The Post-Bush Paulist Brand of Conservatism—A New Configuration of Very Old Elements

In 2007, as the elder Paul launched his presidential bid, leading with his anti-war side, he offered conservatives—as well as the broader public—the promise of a new beginning, untainted by the worst failures of the Bush years, and the passe brand of “compassionate conservatism,” which Bush had adopted to dissociate himself from Newt Gingrich's slash-and-burn style conservatism.

But in reality, Ron Paul had spent his lifetime as a synthesizer of far-right ideas from different groups, working hard to push them into the mainstream. In Chapter 7, (“The Transmission Belt”) of his prize-winning blog series “Rush, Newspeak and Fascism,” (later re-presented in his book, The Eliminationists: How Hate Talk Radicalized the American Right), author, journalist and blogger David Neiwert used the term “transmitter” to describe Rush Limbaugh's role in bringing fringe ideas into the conservative mainstream, as well as helping them cross over from one segment of the right to another. He referred to "Chip Berlet's model of the American right," composed of three sectors, the secular [establishment] conservative right, the theocratic right ['conservative Christians' and others], and the xenophobic right [ranging from "mild-mannered Libertarians" to "neo-Nazis, Klansmen, Posse Comitatus and various white supremacists'], and then wrote:

“Transitional figures like [Arizona county sherrif] Richard Mack and Rush Limbaugh play a central role in the way the right's competing sectors interact. By transmitting ideas across the various sectors, they gain wider currency until they finally become part of the larger national debate.

Neiwert refers to Ron Paul as an example of the the subject of another chapter, “Official transmitters,” where he writes most prominently about Trent Lott, forced to step down from his Senate leadership post the year before because of his ties to the Council of Conservative Citizens, the successor to the old White Citizens Councils. He notes that Lott's connections had been known about for years, before they suddenly became a matter of controversy, and the same would prove true of Ron Paul in 2007, as he ran for president—his first time running as a Republican.

But Paul had been doing much more than Lott. He not only brought fringe ideas into the mainstream, he was also avidly cross-fertilized different segments of the right, based on his own particular brand of paleo-libertarian conservatism, with strong affinities for the Christian Reconstructionism of Jousas Rushdoony, who advanced his version of a biblical blueprint for America, including a division of human affairs into church, family and state, with the later playing only a minimal role, primarily in support of the other two. Julie Ingersoll's recent book, Building God's Kingdom: Inside the World of Christian Reconstruction, provides an excellent introduction to this worldview and its influence. (I interviewed her here for Salon.)

Rushdoony also had strong sympathies for the Confederacy, which he felt came much closer to his theocratic vision than the Union or present-day America—a sympathy shared by both Pauls. Additionally, a key follower, Gary North (Rushdoony's son-in-law) was an early Ron Paul staffer whose ideas about libertarian biblical economics closely mirror Ron Paul's (more on North below). This radical approach to conservative politics offered a very different blueprint for how to draw the different strands of conservatism together than had been dominant before. The multifaceted failure of the Bush Administration opened the door for a fundamental rearticulation of what conservatism meant, and in 2007 Ron Paul, running for president, had the hottest new brand.

Eight year later, the sputtering failure of Rand Paul's presidential campaign to take off, and build on fathers success, signals a significant failure to thrive for this brand of conservatism, even as some of the forces it mobilized and encouraged continue to play a growing role. But there's plenty to be learned from the Paul brand's rise and fall, as the broader currents surrounding it continue with great force.

The Ron Paul Explosion

A few months after Paul kicked off his campaign in February 2007, he began attracting attention like never before in his long career, thanks the early start of the primary debate cycle, with a debate co-sponsored by Politico and MSNBC in Simi Valley on May 3, 2007, followed by a Fox News-sponsored debate in Columbia, South Carolina on May 15. Regarding the first one, Wikipedia notes:

At the end of the debate, MSNBC's online votes showed Ron Paul standing out from the other candidates. Ron Paul won "Best one liner," "Who stood out from the pack" "Most convincing debater", and "Who showed the most leadership qualities?" In all four, he had at least 45% of the total vote.

At the second debate, Paul got into a heated exchange with Rudy Giuliani, over the role that US intervention had played in fomenting anti-American violent extremism, drawing even more support.

The combined impact of these early debates was explosive. Even the progressive-learning Daily Kos diaries and comment threads reflected a lot of enthusiasm for Paul, which is why one diarist, phenry, wrote a powerful 4-part diary series, from May 15 to June 5, laying out who he really was. In the first diary, phenry quoted racist passages from Paul's political newsletters, in the second, he highlighted Paul's broad support among white nationalists and other extremists, and in the third, he specifically cited Neiwert on Paul as a transmitter,discussing Paul's promotion of various conspiracy narratives. Finally, the last part discussed Paul's actual reactionary, rightwing political record, which also diverges sharply from standard libertarianism on reproductive choice and gay rights (a surface reflection of the biblical foundations of his Gary North-style libertarianism.)

Shortly after this, Neiwert and his blogmate, Sara Robinson both weighed in on Paul's actual record.

On June 2, (“Man of the Hour”) Robinson cited phenry's first two diaries while laying out the case that, as she concluded:

The fact is that Ron Paul has built a political career pandering to the far fringes of the proto-fascist right. There's twenty-plus years of documentary evidence that he does not believe in democracy as we progressives understand it. No amount of disarming straight talk should blind us to that core fact.

Commentators brought up Paul's blameshifting disavowal of his newsletters—a dodge that would only grow more central during his 2012 run, when more of the newsletters came to light—and Robinson pushed back in an update, questioning why a so-called “straightshooter” would do this. Two days, in “Six Impossible Things Before Breakfast,” Robinson drew on her own experience as a newsletter ghost-writer for a detailed explanation of just how dishonest Paul's denials were.

“[T]his explanation is beyond bogus,” Robinson wrote, based on how such arrangements work. When she was a newsletter ghost-writer:

My job was to take their ideas, make them sound pretty, and organize the whole into a coherent, readable newsletter. Legally and ethically, it was just as though they'd produced the piece themselves.

Paul's apologists may need to hear that again. Once they paid my fee, all legal rights to it belonged to them outright. It was their intellectual property -- noun, verb, and preposition.

Paul's complete dishonesty in this matter is emblematic of his entire approach to politics. He floats various different outrageous narratives, then walks away as if he'd just said, “How's the weather?” shrugging it off if anyone has gotten upset.

On June 8, Neiwert himself weighed in (“Ron Paul vs. the New World Order”), taking pains to explain how Paul's work as a transmitter made a mockery of naive attempts to portray him as a victim of “guilt by association”:

Ron Paul has made a career out of transmitting extremist beliefs, particularly far-right conspiracy theories about a looming "New World Order," into the mainstream of public discourse by reframing and repackaging them for wider consumption, mostly by studiously avoiding the more noxious and often racist elements of those beliefs. Along the way, he has built a long record of appearing before and lending the credibility of his office to a whole array of truly noxious organizations, and has a loyal following built in no small part on members of those groups.

Indeed, this was actually Ron Paul's business model: “sanitizing” the far-right's noxious extremes for more mainstream consumption on the one hand, getting down and dirty with the true believers on the other. It's this combination of activities that has actively created the hordes of unsavory supporters, whom Glenn Greenwald would later say that Paul should not be judged by.

Neiwert went on to take up Paul's purported rejection of racism, in which he denounced is as "simply an ugly form of collectivism, the mindset that views humans only as members of groups and never as individuals," quoting Paul's argument at length, then pointing out:

This is, in fact, just a repackaging of a libertarian argument that multiculturalismis the "new racism" -- part of a larger right-wing attack on multiculturalism. This is, of course, sheer Newspeak: depicting a social milieu that simultaneously respects everyone's heritage -- that is to say, the antithesis of racism – as racist is simply up-is-down, Bizarro Universe thinking.

Of course that's just it: turning things into their exact opposites, “transforming all values,” is the ultimate form of radical reactionary politics in response to the hard-won struggle for social progress. And that's what Ron Paul had always been up to.

Reality sharply contradicts Paul's claim. As I wrote later that year at Open Left, people with anti-black animus are noticeably “less collectivist.” According to data from the National Election Survey, they show lower levels of support for “a government insurance health plan,” for “government seeing to job and good standard of living,” for “increase federal spending on poor/poor people,” and for “increase federal spending on child care.” In short, “collectivism” and racism are inversely correlated with each other. Far from being the same thing, they lean more in the direction of being opposites.

A Very Positive Development?

The online debate reached an even greater peak following Ron Paul's highly successful “moneybomb” in early November, when Glenn Greenwald wrote here at Salon (“The Ron Paul phenomenon”):

The Paul campaign is now a bona fide phenomenon of real significance, and it is difficult to see this as anything other than a very positive development.

There are, relatively speaking, very few people who agree with most of Paul’s policy positions. In fact, a large portion of Americans — perhaps most — will find something in his litany of beliefs with which they not only disagree, but vehemently so. Paul has a coherent political world-view and states his positions clearly and unapologetically, without hedges, and that approach naturally ensures greater disagreement than the form of please-everyone obfuscation which drives most candidates.

But as phrenry, Robinson and Neiwert argued, Paul is not at all that sort of straight-shooting, straight-talking politician. The is something profoundly deceptive at the very heart of his politics, reflected as much in his shape-shifting methods of organizing, and his blame-shifting way of covering his tracks as in his counterfactual redefinition of terms (such as “racism”=“collectivism”) in order to misrepresent excuses for bigotry as straight-forward moral common sense.

In response, Neiwert noted that (like me) he was “a great admirer of Greenwald's work” but said, “I'm not so sure that this is a largely positive development. In fact, taking in the longer-term picture of where the Republican right is heading, it seems to me a genuinely ominous development with dangerous ramifications.”

Neiwert went on to say:

Greenwald is right, so far as it goes: Paul is consistent and coherent within the realm of his belief system, but those beliefs aren't simply the benign libertarianism that Paul has erected as his chief public image, and which Greenwald appears to have absorbed. Paul's beliefs, in fact, originate with the conspiracy-theory-driven far right of the John Birch Society and Posse Comitatus. He's just been careful not to draw too much attention to that reality, even though he has occasionally let the curtain slip.

As just indicated above, I would go even farther: the fact that Paul is a transmitter, re-presenting extremist ideals in a deceptively “commonsense” framework points to an essentially deceptive mode of politics, one whose sneakiness and covert intentions are routinely projected onto others, fueling his almost addictive attraction to conspiracism.

A Transmitter... And A Transformer? The Christian Reconstructionist Key

If one wants to pull back, and gain an overview of what the elder Paul's politics are, it helps to begin with Neiwerts more basic point about the role of transmitters “transmitting ideas across the various sectors [of the right], [so that] they gain wider currency until they finally become part of the larger national debate.” While different people would divide the right differently, and Berlet's division was meant to be time-specific, the basic idea has tremendous long-standing validity: the American right has long been unified mostly by having a common enemy, at least abstractly, but has repeatedly struggled to draw itself together over anything in the way of a common substantive agenda. Failing any such grand integration, transmitters who can help circulate ideas, narratives, slogans, memes, etc from one sector to another fulfill a valuable makeup role.

But as reflected in his presidential runs, Ron Paul's agenda was always more ambitious than that: he wanted to push forward a vision that would bring those factions together, and be salable to the American public at large as well. And that vision had a great deal in common with Rushdoony, and Paul's former aid, Gary North.

One way to understand what that was is to look at the most enduring division the right has faced for at least 100 years—that between social conservatives (epitomized by the religious right) and economic conservatives (epitomized by libertarians). During the Cold War era, anti-communist/foreign policy conservatives formed a third group, often providing a unified rationale for all, but as communism fell, the more irrational conspiracist elements of anti-communist conservatism began mutating in ways that continue to this day. Ron Paul is ostensibly a libertarian, but with biblical roots that put him much closer to traditional social conservatives than classic libertarians are. These roots also inform his conspiracist anti-modern banking views, providing deep ties to the conspiracist flowering that followed the Cold War's end.

As Ingersoll's book explains, Reconstructionists do not approach politics in the same way that most others on the Christian right do. They are not interested in taking over government power in the name of religion, but rather in shrinking government dramatically. Relatedly, their libertarianism also has Biblical roots, partly derived from the same idea: government has no role in the economy. As already mentioned, a main figure in Ingersoll's book is Gary North, a Ron Paul staffer during Paul's first stint in Congress in the 1970s. In the interview, Ingersoll explained:

[F]or Reconstructionists a lot comes down to property and therefore economics is crucial. And in sphere sovereignty (that division of authority into family church and civil government) all economic activity is a function of the family....

I’ve heard North say, “Rothbard and those guys [Austrian School theorists associated with the Mises Institute] they really get biblical economics, they don’t understand that it comes from the Bible. So they fall down in humanism. But the economic framework that they advocate is the biblical economic framework.” So for North it’s because this is a function of family, and family authority is autonomous from the civil government’. This pairs very nicely with a libertarian view of economics that says the government should stay out of economic choices and economic decisions.

Ingersoll also explains how there is a deep neo-Confederate strain in Reconstructionism, which is also reflected in Ron Paul's ideology. Seeing government's involvement in the economy as illegitimate, this feeds into all manner of militia-style conspiracist ideology as well. When the financial crisis hit, it supercharged economic fears which gave tremendous impetus to the economic conspiracist element of the right. Hence, all the pieces Ron Paul sought to bring together reflect interlocking aspects or consequences of Reconstructionist thought—although, as with the Austrian School economists mentioned above, those being drawn into it may not realize what they're being drawn into.

Nor, to be honest, is it anywhere close to clear how closely Ron Paul's politics align with Rushdoony's or even Gary North's. Simply put, he's never been pressed to explain. Journalists who might have been in a position to ask such questions did not have the background needed to pose them. So there's a degree of vagueness involved when we try to specify exactly what Ron Paul's political project was, and how fully it embodies Reconstructionist thought. But there's no doubt that Reconstructionism provides a broad-based key—at the very least—to make sense of the otherwise often bewildering flux of fringe beliefs that Paul embraced, and helped circulate between different factions on the right.

For at least two presidential election cycles, the combination of concepts that Ron Paul brought together made a strong bid to rigorously restructure the framework of American conservatism, at a time when the existing, looser framework under George W. Bush and his allies was starting to disintegrate. While some of the themes that Paul focused on—the ersatz anti-federalist “constitutionalism”, for example—were picked up by others as well, and seem destined to continue being influential, regardless of how ill-founded they may be, the larger overall integrated framework he was pursuing seems to have fallen apart much like Bush's “compassionate conservatism” did, without ever getting a short at real power.

The Dynasty Problem

The problem was probably not with the ideas—problematic as they might have been—but with the hand-off to Paul's son, who was simply not as skilled as his father was. Although, it could be argued that Rand faced challenges in his higher-profile role that his father never seriously encountered, he was raised in the best possible environment for developing the capacity to take on that challenge. So it all comes back to the man himself.

“Family dynasties don't always work,” author and researcher Frederick Clarkson told Salon. “If they did, we would be seeing a lot more Kennedys in national life than we actually have. Camelot is long gone.”

“I ascribe his failures to the difference between Rand and his father,” Neiwert told Salon. “Ron, for all his flaws, at least had that mad glint in his eye that that gave off the appearance of crazed integrity, which was a lot of his appeal. Ron's admirers were always glad to admit that he was a little nutty, but that just made him seem authentic to them,” he said. That claim of authenticity was invoked repeatedly—the Greenwald quote above is but one example.

“Rand gives off no such aura,” Neiwert continued. “He has a spoiled frat boy's demeanor, comes off as a cynical and not-particularly-sharp clone of his dad, and his frequent petulance on the campaign trail has been fatal to the kind of appeal he needs to make in the world of right-wing populism, which is what he is mining by exploiting his father's 'libertarian' legacy.”

“Rand is no Ron Paul,” Clarkson agreed. “He is in a peculiar position, seeking to broaden the Paul family based without alienating it. I think he has failed rather badly on that score -- traveling to Israel, speaking at Howard University in a badly handled pander to African Americans. These acts did not endear him to his base, and did not establish him as smart pol who can navigate the difficulties of history and demographics,” Clarkson said, adding, “It is hard for him to be his own man and to be his dad at the same time,”

“I think it's telling,” Neiwert added, “that the Tea Party -- which was tailor-made, with its empowerment of the Patriot types, to a Ron Paul-style candidate, especially a young version of him -- is not enamored of Rand Paul, nor is he deeply entwined with them. There's a bit of distaste there that I suspect is mutual.”

The Reality Problem

While Rand's personal shortcomings are certainly crucial, there's another factor as well: He's actually attempting to engage with folks whom his father rarely dealt with at all. He was trying to make a transition that his father never prepared for—and neither did he. To illustrate this point, consider two examples of how father and son fared quite differently pushing their alternative history views of what civil rights are all about, due to the widely different contexts they were operating in.

In 2007, as he was running for president, Ron Paul gave an interview that went up on Youtube, in which he compared a couple of gun-toting “patriot” tax evaders, involved in a months-long armed standoff with federal agents, to Ghandi and Dr. Martin Luther King. It was not wildly unusual for Paul to say such things, but it got a fair amount of buzz, relatively speaking, and I wrote about it for Open Left, going into some of the details that Paul blissfully glossed right over: Such was the isolated world the Ron Paul lived in, even as he was running for president, that no one ever challenged him for this outrageous claim.

It was also the sort of ideological cocoon in which Rand Paul was raised, and that’s where things got problematic. Three years later, in 2010, Rand Paul was running for US Senate in Kentucky. He had just won the GOP primary, and he went on The Rachel Maddow Show, where he had first announced his candidacy a year before. The Louisville Courier-Journal had declined to endorse either candidate in the GOP primary, citing Paul’s opposition to aspects of the 1964 Civil Rights Act—a story that had gained a great deal of attention that day. Maddow then followed up on it.

[video here/Salon coverage here]

Paul was clearly annoyed about even being asked, and tried to minimize the extent of his opposition, saying, “There's 10 different titles, you know, to the Civil Rights Act, and nine out of 10 deal with public institutions…. When you support nine out of 10 things in a good piece of legislation, do you vote for it or against it? And I think, sometimes, those are difficult situations.”

As the controversy unfolded further, Paul even claimed that he would have marched with Martin Luther King—but not necessarily voted for the Civil Rights Act.

There were two main problems for Paul. First and foremost, the civil rights movement was not solely, or even overwhelmingly concerned with government discrimination. A great deal of the battles involved had to do with fighting against private discrimination—such as the famous sit-in movements aimed at getting integrated service from private businesses throughout the South. Maddow and others in the media knew this history, and unlike the like-minded interviewers that his father routinely faced, they were not about to let Rand Paul simply stand history on its head.

Another problem was less noted. As I pointed out at Open Left, “There were actually at least six titles in the 1964 Civil Rights Act that Paul would have had problems with at the time, given his expressed ideology. And there are two more, dealing with voting rights, that he might well have problems with today, given the widespread hatred Tea Baggers have for ACORN.” In short, Paul profoundly misunderstands both the civil rights movement itself and the 1964 Civil Rights Act, even as he tries to portray himself as a moral champion who would have marched with Martin Luther King.

This certainly proved deeply embarrassing for Paul. He tried to blame Maddow for being out to get him, and broke off their once-friendly relationship. But it’s hard to see how his father could have fared any better. His father had the cunning to avoid putting himself in that sort of situation. But given Rand’s much higher ambition level, that option simply wasn’t available for him.

The problem Rand faced was a truly daunting one, even if he had been a much better politician than his father was. For what he needed was not just individual skill, but widespread, coordinated, institutional support, sufficient to silence the media and make campaign reports as supportive of his revisionism as his own ideological fellow-travelers. Marshaling such power was clearly beyond him, and not surprisingly: his father had never dreamed of building power on such a scale.

The Brand Has Failed, Rebranders Are Just Getting Started

But even now, all of the GOP presidential campaigns are engaged in a process that could well move in the direction of doing what Ron and Rand Paul could never even dream of: completely controlling the political environment in which they run for the highest office in the land, spinning out their fantasy versions of America's past, present and future. Although there's clearly no specific agreement on how post-Bush conservatism should be redefining itself now, there is broad agreement that reality [aka “gotcha questions” about debt ceilings, civil rights, global warming, etc.] should not be allowed to intrude on the process.

The collapse of the Rand Paul brand is not without its lessons for the broader field of conservatism's reinventors who show no signs at all of slacking off. But it's not without its lessons for the rest of us, as well.

We have been warned.

Shares