The Islamic State is the wealthiest and most

How did the situation get so bad? Without a doubt, the Islamic State’s apocalyptic vision has attracted many recruits from around the world. What could be more exciting than fighting the forces of evil in the grand battle for cosmic justice? As one jihadist told Reuters in 2014, “If you think all these mujahideen came from across the world to fight [the Syrian leader] Assad, you're mistaken. They are all here as promised by the Prophet. This is the war he promised – it is the Grand Battle."

It may be tempting to blame religion for this quagmire. And this wouldn’t be entirely incorrect: By their own admission, many Islamic State militants are motivated by religious convictions. But a question that many secular observers, such as Bill Maher, fail to ask is why these young men and women accepted their extremist beliefs in the first place. As scholars of apocalypticism will point out, in situations of great violence and upheaval, humans often adopt apocalyptic frameworks through which to interpret, and thus give meaning to, the desperate situations in which they find themselves.

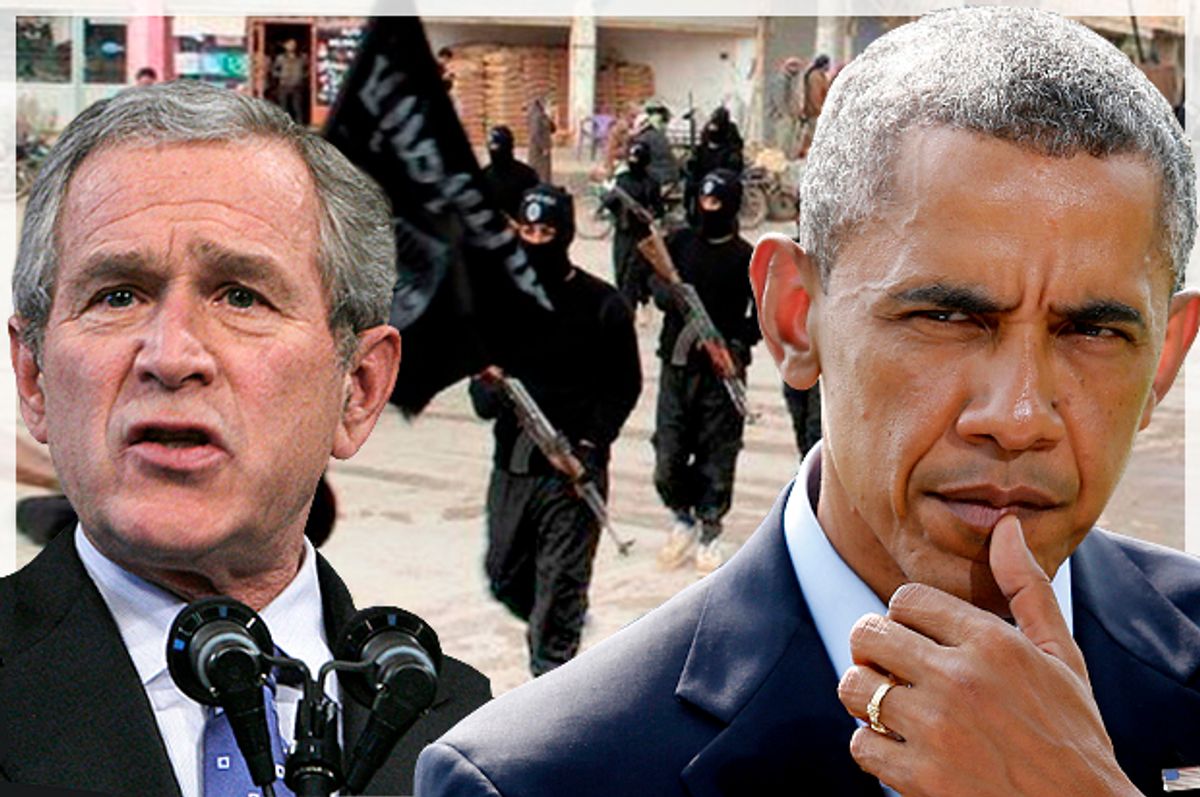

The 2003 U.S.-led preemptive invasion provided just such a situation, one that could easily be seen as an apocalyptic confrontation between the Muslims and the “Roman” forces discussed in prophetic hadith. As Graeme Wood notes, “During the last years of the US occupation of Iraq, the Islamic State’s immediate founding fathers … saw signs of the end times everywhere. They were anticipating, within a year, the arrival of the Mahdi.” The Mahdi is Islam’s messianic figure, and it's said that he will lead the Muslim armies against their enemies and usher in a world of justice before Jesus descends in Syria to kill the Antichrist in Israel.

More bombs dropped will thus only reinforce these beliefs and provide further "evidence" that this really is the Grand Battle that Muhammad prophesied. Those of us in the West seem to recognize this problem when it comes to the actions of others, such as Russia. After Vladimir Putin ordered airstrikes against opposition forces in Syria, the U.S., the U.K., and Turkey voiced concern that Russia’s actions would “only fuel more extremism.”

But why is our military involvement any different? Sure, we aren’t bombing the Syrian opposition (which is clearly a good thing), but there’s hardly any doubt that the U.S.'s preemptive invasion and subsequent occupation of Iraq galvanized a whole generation of moderate Muslims to become violent jihadists. In an interview with Vice News, for example, an Islamic State fighter poignantly states, “God willing the Caliphate has been established, and we are going to invade you as you invaded us. We will capture your women as you captured our women. We will orphan your children …” at which point he begins to choke up, “… as you orphaned our children.” He then starts to cry.

What the Western Coalition needs to recognize is that Islamic terrorism in its most recent manifestation isn’t a supply-limited phenomenon, it’s a demand-driven phenomenon, to borrow a term from Robert Pape of the University of Chicago. We can keep playing “whack-a-mole” for the next three decades, taking out Islamic State leaders and their supporters, but this is unlikely to bring lasting success. With every terrorist killed, another terrorist — or two, or three — joins the Islamic State. According to one count, the Islamic State is suffering about 1,000 casualties a month as a result of Coalition airstrikes, while at the same time it’s recruiting roughly the same number of foreign fighters.

If terrorism is a demand-driven phenomenon, then perhaps we should try to eliminate the demand driving it. One way to do this would be to undermine its apocalyptic propaganda. There are two options here: first, we could meet the Islamic State in Dabiq and decimate its army with our superior military might. Or second, we could withdraw from the region, focus on winning hearts and minds in the Islamic world, and consequently deflat

The conspicuous disadvantage of the first is that it offers, at best, a short-term solution to the ongoing problem of terrorism in the Middle East. It might succeed in destroying the Islamic State, but it would likely invigorate yet another generation to chant “death to America” with AK-47s thrust into the air. The cycle of anger and violence would continue.

How many times must we go through this cycle? The U.S. and Europe have a long history of Middle Eastern intervention, and the Islamic State is well-aware of this. When it bulldozed barriers between Iraq and Syria in 2014, some tweeted pictures, excitedly declaring that they were demolishing the Sykes-Picot border. We’ve tried military intervention in the region for decades, and the results have only led us to the present quagmire. Perhaps it’s time to try a different strategy.

Shares