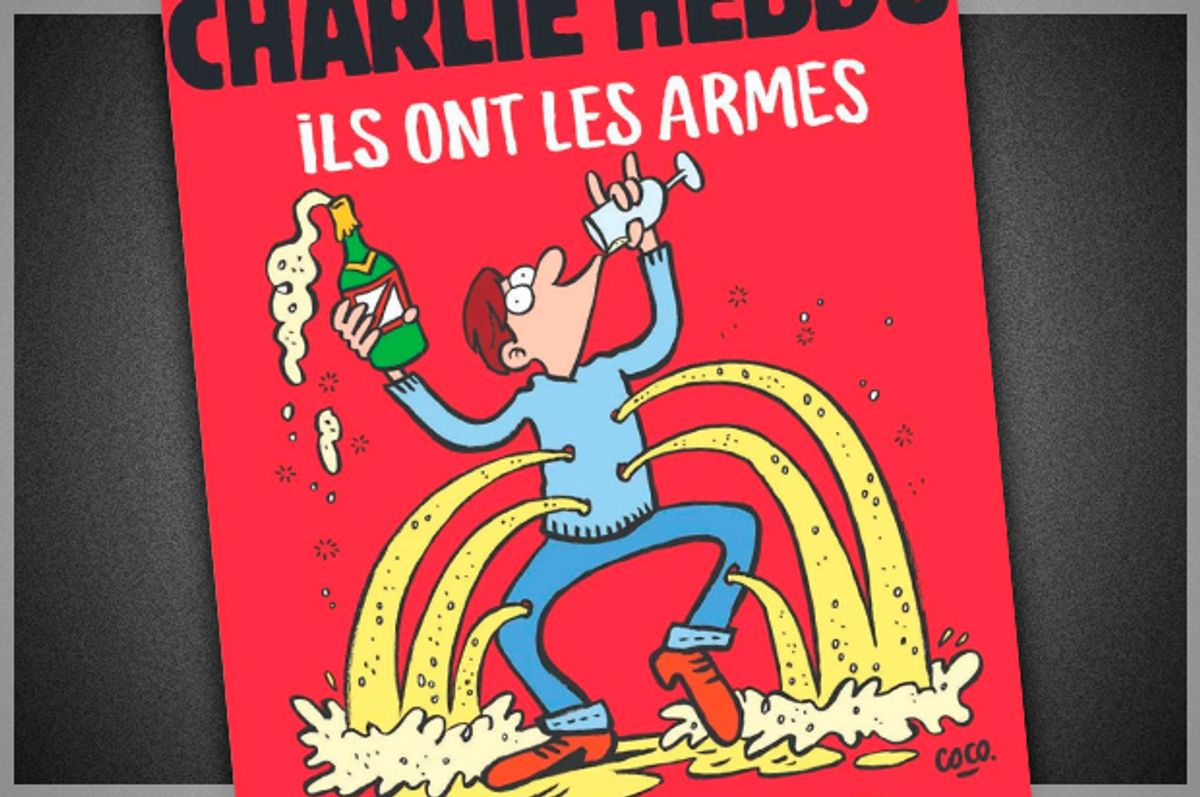

Yesterday, the French satirical magazine Charlie Hebdo published the first of its weekly issues in the wake of the terrorists attacks on Paris that killed at least a 129 innocents and wounded scores more. Drawn by Corinne "Coco" Boer, the cover presents us with a Frenchman determined to keep the joie in the vivre for as long as he is still standing. The Charlie Hebdo caption states: "They have weapons. Fuck that shit. We have champagne! (Ils ont les armes. On les emmerde. On a le champagne!)" Pierced by bullets, he is bleeding champagne as he continues to drink and dance in spite of his mortal wounds.

It is exceptionally difficult to do justice to a state of national mourning using the tools of satire. A funeral is no time to point out the fatal flaws of the dearly departed, yet satire's job is to critique those in power, or to expose the flaws in our collective delusions. Some may object to levity being injected into this subject. It might be construed as being disrespectful toward the victims and their families. But given that this is not the cover of any satirical magazine but Charlie Hebdo, itself the site of a terrorist attack that killed twelve staffers just a few months earlier, Boer asks us to see the black comedy in the dancing Frenchman's absurd determination to finish off his bottle, making us understand that humor is a defense against despair.

Even as the president of France has declared that "France is at war," Charlie Hebdo has now declared that it is engaged in a "war of images." Mincing no words, Antonio Fischetti stated: "The Islamic state did not invent much. In any case, not the suicide-attack...Up to now, the use of the image in wartime answered a simple rule: each camp sought to present itself in the best light and to portraythe enemy as the worst possible." But with the Daech (in English, Daesh, which is ISIS), he shrugs, "it's no longer necessary to tire oneself in blackening the enemy, because they do that themselves, and better than anyone."

For the time being, however, Charlie Hebdo is getting geared for battle instead of picking fights. A few days ago, the website posted a cartoon drawing of ghosts wearing berets and carrying baguettes tucked under their arms, with the caption: "The French resume normal life (les francais reprennent une vie normale)." The drawing is both charming and inexpressibly sad, focused on Paris in mourning rather than caricaturing the Daesh.

For the cover of the Nov. 18 issue of Charlie Hebdo, Boer similarly focused on the wounds to France's body and soul. Wearing jeans and a crewneck sweater, the young man would have fit right in with the crowd at the Bataclan as he wraps his left hand around the wineglass while raising his index and pinky fingers in the rock salute Sign of the Horns. (The American band playing the venue that night was "Eagles of Death Metal.") Given his youth and the lack of pain in his expression, there are subtle references to the piercing of the body of martyred St. Sebastian, who himself incarnates the suffering of Christ on the cross. The spirits pouring from his wounds invoke the transubstantiation of wine into Christ's blood, while reminding us that wine runs metaphorically through the veins of France.

But substituting champagne for red wine makes the image more secular, and it could equally be argued that drawing was also meant to evoke Kali, Hindu goddess of Time. As destroyer of many evils, she thus has many arms--for she is a warrior, and well armed--and is often portrayed dancing. One of her attributes is a cup she uses to catch the blood of her enemies. Our Frenchman is using his cup for bubbly. But on the whole, these references are art historical echoes, from which no image is truly free, and have nothing to do with the drawing's specific aesthetic sensibilities.

Boer's cover does not strive to achieve artistic greatness but to function as caricature, and for that reason alone it might be seen as contentious. This past May, Charlie Hebdo received a "Freedom of Expression Courage Award" from the international writers and human rights group, PEN, an honor that prompted over two hundred authors to boycott the ceremony in protest. The protesters decried its caricatures of the Prophet and other religious figures as hate speech, whereas supporters argued that their equal-opportunity offensiveness stood up to religious intimidation.

This cover of a slightly inebriated Frenchman will raise no similar alarms. Instead, it turns attention back to the magazine's higher mission to fully defend human rights around the world, which also includes the right to be in bad taste or defend unpopular opinions. In the wake of the terrorist attacks that killed 12 on its staff, the website posted a long, impassioned editorial pointing out that a nearly identical attack had occurred in Bangladesh, and the world press paid no attention to it, anticipating nearly identical criticisms this weekend regarding the lack of press focused on similar attacks in Beirut. The editorial staff at Charlie Hebdo affirmed: "the respect of individual rights and secularity is a necessity for everyone on this planet." How they go about defending these rights may not be everyone's cup of tea, but for the next few days, it will surely be a popular glass of champagne.

Shares