Via Twitter, texting, and other social media platforms, it was easier than ever to find out if friends, colleagues, and family in Paris were okay in the wake of what France 24 declared a “French 9/11. The whole world is in danger.” Whether directly or via friends of friends, I knew almost instantly that the people I knew personally were physically unscathed.

But having been in Paris on 9/11 and finding myself unable to get through to friends in New York City, it was against that memory of not-knowing that I first saw the Facebook status announcing SAFE for one of my French family members in Paris, even as steady updates regarding the attacks were popping up in my Twitter feed. Then a SAFE notification popped up for another. And another.

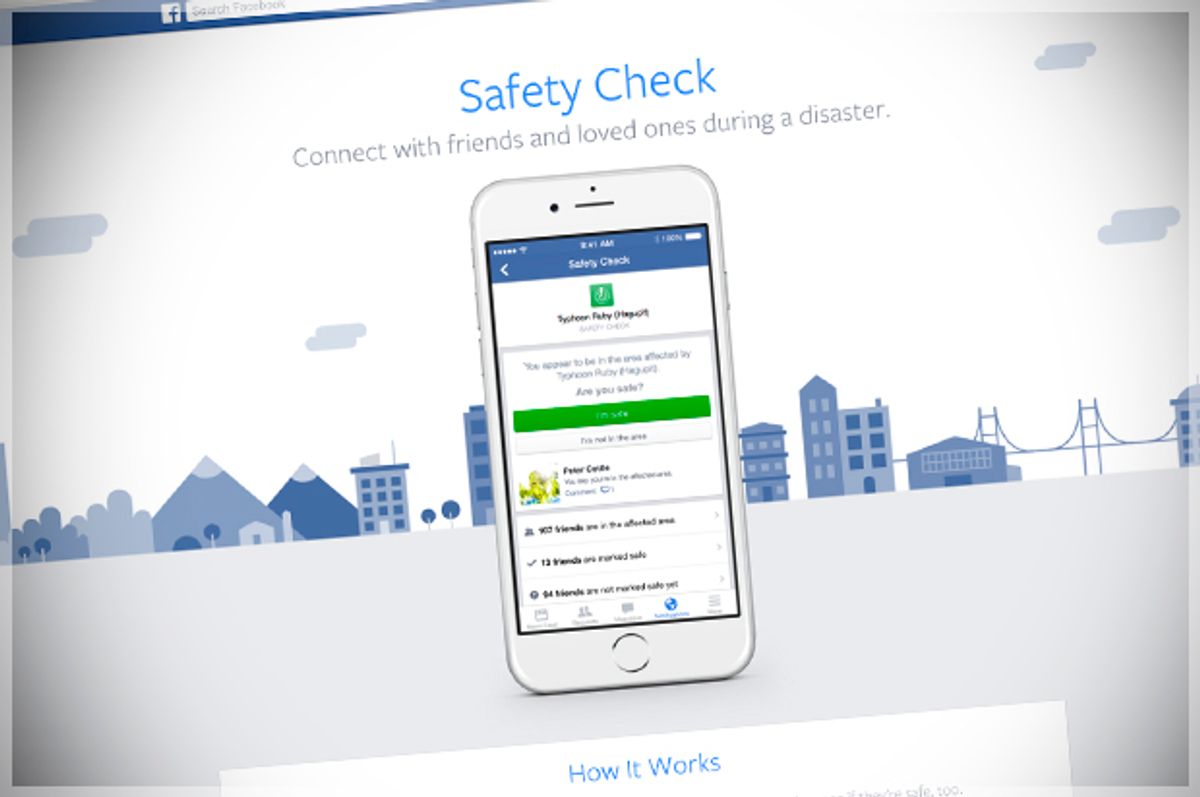

I was curious, so I fished around, trying to see if I could activate a SAFE notification for myself. Nope. It’s something that Facebook elves turn on for you, based on the city indicated in your profile and where your devices think you are. If you’re in an affected area, the Safety Check feature gets turned on. This is just a fancy way of saying that Facebook tracks you better than Santa, but at times like these, nobody cares about the epistemological implications regarding privacy, surveillance, or the increasing impossibility of functioning autonomously outside of a networked media system. Instead, to even challenge the steady process of mediatic assimilation marks one as a relic of a worldview rapidly being marginalized as anti-progressive and anachronistic.

The “safety check” feature on Facebook grew out of a need identified in the wake of Japan’s earthquake and tsunami of 2011. The feature was implemented in October 2014, but Paris was the first time it was activated for an act of terrorism instead of a natural disaster. It came under immediate criticism for its implicit Eurocentric bias. Why wasn’t the four-year-old feature activated immediately when nearly identical terrorist acts murdered similar numbers of civilians in Beirut? It was turned on after Boko Haram bombed Nigeria yesterday. Will it be turned on for the people of Bamako, Mali, currently the site of an unfolding hostage situation at a luxury hotel?

What we talk about when we talk about Facebook flags and safety check features is really about something else, which is why their implementation (or lack thereof) generates so much free-form anxiety. It boils down to the nagging sense that our Freudian slips are showing, and that the features reveal the uncomfortable fact that “some terror victims deemed more newsworthy than others.” In other words, we’re getting the media we deserve, says Jeff Yang. Facebook merely reflects the vagaries of a consumer-driven media market. And safety check shows that some humans are more equal than others, because technotopia is not a universal.

As reported by the New York Times, Facebook’s policy of when to activate it is still developing. “There has to be a first time for trying something new, even in complex and sensitive times, and for us that was Paris,” wrote Alex Schultz, the company’s vice president for growth, adding that Safety Check is less useful in continuing wars and epidemics because, without a clear end point, “it’s impossible to know when someone is truly ‘safe.'”

And that is the crux of the matter. Where in the world, now, are we safe? More importantly, is the binary safe/unsafe even legitimate to assert, or does that continue to foster a false narrative promising that if we only get from troubled here to peaceful there—say the land of Oz-- we will be able to exhale in relief?

***

Lois K.’s daughter is somewhere in limbo. American Heather K. had first met Aurélian, a Frenchman, on a couch-surfing adventure that took her to Toulouse, France. Then she began “wwooffing,” or volunteer working on organic farms and smallholdings as a way to see the world. She and Aurélian skyped each other for a year, and then the two of them moved to New Zealand, as a way to see if their relationship could work in real life.

By now, they’d been in New Zealand for a year. Together, Heather and Aurélian had gone to Australia for three weeks for a great adventure. Heather was supposed to be coming back to the U.S. this Wednesday, and Aurélian was heading to France. Lois tells me she was on the phone with her 27-year-old daughter, and had asked her directly if she had gotten engaged. Annoyed, her daughter hung up the phone. And the very next moment, as she sighed in motherly exasperation, Lois became aware of the news in Paris. She kept saying to herself, “uh oh.” There was no point in calling her daughter again, because Heather’s cell phone is in a drawer at her home. For someone wwoofing as a way to travel, it’s too expensive to call international on a mobile, and Heather was using up the very last of her funds to return to the US. Lois has to wait until her daughter calls her collect on a pay phone or ventures into an internet café. Meanwhile, she doesn’t have Aurélian’s contact information and he never checks Facebook. She assumes he’s going to be stranded in Australia indefinitely, unless he ends up coming to the U.S. with her daughter. Which is, on multiple levels, the best case scenario for everybody.

These are 20-somethings living mostly offline, and their middle-aged mother, who has worked in the post office for thirty-one years, finds herself wondering if they are okay and where Aurélian will go. Mostly, however, she is wondering what their future will look like.

Is this adventuresome pair in an “unsafe” zone? Not at all, and yet the events of Paris are having real repercussions for them, just as they are for travelers everywhere trying to get back home. And it is accurately "them," not just him, for the status of your loved one implicates your existence as well. A button on Facebook does little to assuage Lois’s larger worries for her daughter and her boyfriend, though in the short term, it would certainly help silence the gremlins chittering in her head if she simply knew they’d reached the airport.

In every circumstance, technology is only as good as its operators. As it happens, the Facebook “safety check” feature also lets other people mark you SAFE. This makes sense, given that not everyone in an emergency situation will have battery power or be able to get online. But I tend to use social media incorrectly, and expected that I would futz up the SAFE button were I able to make it go in the first place, which is why I wanted to try it out in advance of an emergency. As I was chatting with Lois about her daughter, a woman named Theresa (who likewise asked that her last name be withheld) told me that a friend of hers in Paris had accidentally marked people “safe” — those who were no longer living in Paris, as far as the friend knew — using the new feature. "I wanted to keep people from being thrown into a panic, but in doing so I may have caused just that," the friend posted in apology.

Similarly, Twitter hashtags such as #PorteOuverte (open door), was supposed to be a way for stranded tourists to find someplace to crash, but became overwhelmed by well-wishers using it simply to tweet out their support. In other words, the existence of technology creates as many problems as it solves. It is not a magic button that makes the ills of the world disappear, but a panacea, a sigh of relief, a good-to-know and onward with the business of ordinary living.

What is true is that Paris was and remains a cosmopolitan city, a city now showing us the 21st reality of a world that is interconnected in frightening and wondrous ways. As a cosmos in miniature, it is an aspirational site that is as much an idea as a destination. Famously, playwright Oscar Wilde quipped, “When good Americans die, they go to Paris,” prompting the inevitable rejoinder, “…so where do the bad ones go?” (The answer: also to Paris.) Safety is an illusion, and always has been. Which doesn’t mean that fear of the unknown should drive domestic and foreign policy. Quite the contrary. By embracing 30,000 refugees in the wake of the attacks, vowing to remain a “country of freedom,” France has found true strength within tragedy.

But the fact that Safety Check allows us to virtually confirm—or so we believe—that those whose well-being we can’t verify in person are doing okay, it also doesn’t mean that the technology we implement must be neutrally benevolent. The same vectors that allow fear & paranoia to travel instantly across great swath of time and space, makes it equally possible to breathe easy in the knowledge that your loved ones are as safe as they can be.

As a postscript: Heather made it back to her mom. Aurélian made it back to France. They are engaged and planned to be married next year in France. Lois and her family are saving up to go to the wedding.

Shares