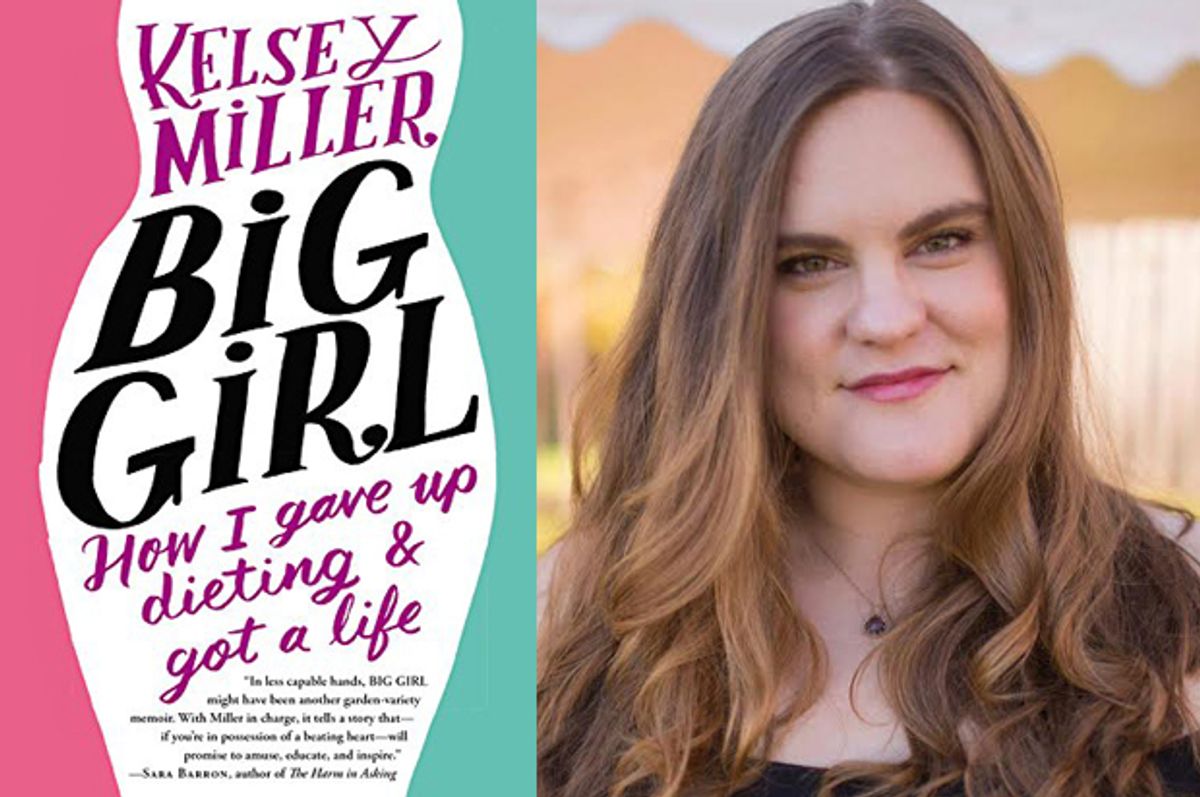

Masses of Americans will resolve to lose weight for New Year’s, but Kelsey Miller, a senior features writer at Refinery29 and author of the upcoming memoir "Big Girl: How I Gave Up Dieting and Got a Life" (Jan. 5), would propose a different solution to body image woes.

Miller struggled with her weight since childhood and hopped on and off fad diets throughout her teens and twenties. It took collapsing in the woods after a failed “Spartan Warrior Workout” for her to realize this method wasn't working. She had tried the same thing — dieting — for years and expected different results, the oft-cited definition of insanity. The outcome, of course, was instead the same: She’d grow miserable, relapse to “unhealthy” eating, and end up back where she started, eager to check another weight-loss regime off her list.

So at 29, Miller embarked on a fast from fasting itself, chronicling her experiment in Refinery29's Anti-Diet Project column. Secretly, she hoped this new approach would somehow help her shed pounds. But when her nutrition therapist asked if she'd be okay never losing an ounce through intuitive eating — consuming exactly what she was hungry for — she was forced to reconsider what health and fitness meant.

At a café in her home borough of Brooklyn, Miller told Salon about what she learned along her diet-free journey, the toxic messages the media sends about food and weight, and the advice she'd give others seeking a saner relationship with their bodies. The interview has been condensed and lightly edited for clarity.

At the beginning of your book, you ditch dieting in favor of a new philosophy called intuitive eating. Could you explain what intuitive eating is?

It sounds like a fake thing, and that’s what I thought it was when I first heard about it, before I quit dieting. I’d stumbled across it a couple times and thought it sounded sort of adorable and crunchy and like something I should probably definitely do, but not yet — when I was thinner.

When I had the big turning point, that phrase was hanging around in my head. Really, it’s just diet deprogramming and learning to eat like a normal person again. For better or worse, most of us don’t have a sense of the way we ate when we were 3 years old, when we weren’t afraid of basic carbohydrates. It’s learning to eat again as if you were a child with all those instincts firmly in place, before they got polluted by diet culture and outside influence. It’s having full permission to eat whatever. Nothing is going to make you a bad person if you eat it. And then it’s monitoring your fullness, which is just a very fancy way of saying, “You eat when you’re hungry. No matter what, you do it. And when you’re full, you acknowledge that.”

Some people think it means you can only eat according to hunger and fullness and there’s no leeway for when you’re just like, “Oh my God, that cookie looks really good.” But of course you’re allowed to do that. I have a friend who’s an intuitive eating coach who references birthday cake as a case of “emotional eating” that’s important. We eat birthday cake for a reason. If you’re really not in the mood and you don’t feel like it, you don’t have it. But you don’t eat birthday cake because you’re like, “My body really needs some birthday cake right now, and I’m going to honor that,” and that doesn’t make it illegitimate.

Can intuitive eating include consideration for what is healthiest to put in your body? Or is that its own form of disordered eating?

That was my fear when I started. I really thought I was just going to eat pizza until I died of pizza. But the truth is, when nothing is off limits and you’re eating mindfully, you realize pizza is good, and then too much pizza doesn’t feel good. And if you have a sense that there will always be pizza, you can always get more pizza, and it isn’t going anywhere, you’re not going to have that need to eat all the pizza when it’s in front of you. That sense of deprivation is really what leads to overeating.

Once you have a sense of security around food and you’re not approaching food with a sense of deprivation and fear, absolutely, you can think of nutrition. I’ll have the thought sometimes, “There aren’t really a lot of vegetables in my breakfast this morning. I’ve got to get some greens in there.” I know my body feels better when I have roughage in it. Most people who have been dieting their whole lives have a sense of what’s healthy and what’s not, and the issue is that a lot of the ideas we form are a perversion of health. Instead of being like, “I don’t want to eat too much sugar because obviously I know that eating cups and cups of sugar won’t make my body feel good and function well,” we end up thinking, “Sugar is Satan, sugar is the devil, and if you eat sugar, I’ll call the police.” That sense of moralization around food and healthiness is different from wanting a vegetable on my plate.

The association between food and morality was a major theme in your book. You wrote that while you were dieting, you viewed eating after 7 p.m. as "a crime on par with infanticide." How do you think we learn to assign moral value to food?

Man, we should write a thesis on that. I’m sure there is one somewhere. But, for one thing, we associate thinness with goodness and restriction with being good. “I’m being good this week” — that kind of thing. So, our language and the way we perceive and talk about food totally foster that connection. On the flip side, we hear about junk food and garbage food and poison — “gluten is poison,” people say — and so we take it to extremes. That’s the other side of the perversion of healthiness: that sense that I’m a bad person if I eat refined bread. It’s really hard to let go of that.

Also, we have what we’re told growing up: what you should eat, when you should eat, what you shouldn’t have too much of. If I ate too much of something that my mom or dad didn’t want me to eat, I felt bad. I felt like I did something wrong. It starts very early, and the way we talk about food in the media totally feeds into that moral discussion.

Do you think that’s a problem for women especially?

I think it is for everybody, but certainly women are far more targeted by the diet industry. Obviously, men pick up on these things a lot, and we don’t talk about it with men. I don’t think a lot of men feel as comfortable talking about these things. There’s a lot more crossover than there used to be, but I think there’s an emphasis on women. If you look back, we associate women with morality, so why wouldn’t we associate women with purity and health and thinness?

What do you mean when you say we associate women with morality?

I’m thinking of the righteous wife, “pure as the driven snow,” all those archetypes of women in literature. Women are often described as virgins or whores, and those are just the opposite sides of morality.

It seems like there are two opposing movements in this country right now. On the one hand, there’s the push away from moralizing food and bodies, toward body positivity and fat acceptance. On the other, there’s this fear of the so-called obesity epidemic, which some medical professionals and public figures like Michelle Obama are trying to combat. Do you think there’s room for both, or is concern for health just fat-shaming in disguise?

The health-at-every-size movement has shed light on some interesting things, and this is an ongoing exploration, but the fact that people react to fat positivity and health-at-any-size should tell us something.

The way we associate size and health is clearly wrongheaded. It’s vitriolic and hateful and just speaks to this enormous bias that’s absolutely endemic across our culture. That is something we need to take a good, hard look at. We should be addressing the foods we’re feeding ourselves and our kids, but we also need to be acknowledging and thinking about the way we feed them and the way we feed ourselves.

We all know there are some people who are just going to be bigger naturally and some people who will be smaller naturally, and there are some people who are going to be bigger because they are eating poorly or they’re eating in a disordered way or they’re just overeating. There’s a lot of reasons behind that, but it’s not as simple as “fat person = bad, unhealthy person.” That moralization of health is in there because there’s nothing but shame and disgust in the way we talk about fatness. We have to address a lot of the foods we eat but also the way we talk about our bodies. If anything’s an emergency, that’s an emergency as well.

But the quote-unquote obesity epidemic is a complicated matter, and I have no question that the people behind that are trying to do something good. Nobody wants American children to eat piles of mac and cheese nonstop and no vegetables. But why aren’t we talking about that instead of saying, “We have to fix our fat kids?” We now know that shaming and restriction haven’t gotten us very far. They have never made anybody any thinner or healthier or better. Why isn’t that part of the conversation more? That needs to be a global discussion as well.

It seems like your experience with disordered eating without a diagnosable eating disorder is really common. What are some signs that your eating habits could be disordered?

That’s a really important distinction a lot of people don’t recognize yet. A lot more people have disordered eating than eating disorders. If any part of your day or your life is anchored around food, that’s a disordered behavior. If you have a moral attachment to a way of eating, that’s a disordered behavior. It’s a little complicated because there are people like ethical vegans who aren’t necessarily eating in a disordered way even though there is a morality there. But I think you have to take a hard look at yourself, which is very difficult, and say, “Am I engaging with this food in a way that is neutral by treating it like food, or am I treating it like something else?” I think food neutrality is the barometer there.

Could you explain what you mean by “food neutrality?”

The example I use in the book is that French fries were the ultimate food on my bad list, versus kale, which was like the saintliest of greens and just feels like you’re eating Gwyneth Paltrow’s blonde hair. It’s like you’re consuming something so pure and good and it’s making you better, whereas you have to eat French fries in a dark room alone so nobody can see this terrible crime you have committed, and you have to repent with kale and eat it in the presence of a thin person.

That’s the food neutrality issue: when you’re treating food as something other than food. Even people who use words like “I’m so bad! I just ate a ton of French fries” — in the end, if it’s not haunting you but you’re still like, “Well, I ate the French fries. That’s too bad I ate a huge pile of French fries,” you’re still engaging with it like it’s not just food but the thing defining your moral character.

That’s really difficult to let go of. I can’t look at a potato and not see Weight Watcher’s points. My brain just has that data, so I have to consciously look at a potato, and I hear the points in my head, and I tell myself the rest of the story about the potato: “This is the potato. It’s a potato. It is not something I’m going to have to make up for. It’s a vegetable. It’s a starch. Do I want it? Am I hungry? Do I crave it?” I ask myself a bunch of questions to bring it back to what it is: just a potato, nothing more.

What did you gain from dieting that made it so hard to give up? How do you get those things now?

The thrill. The thrill of the new diet and the fantasy that comes with it. Every time you start a new diet, you really believe this will be the one to change your body and that everything in your life will be a million times better and more magical when you’re done. They don’t say, “When you’re finished with this, you’ll have a pony,” but it’s basically implied. They imply that everything will be wonderful. And then, of course, there’s the comfort of failure. It’s all very familiar to start something new and then have some success and then stumble or plateau and then fail and then just reverse to that binge-y period in between diets.

I won’t say I don’t miss that structure. I don’t want it, but it was a loss in my life. And I’m glad. I willingly sacrificed it because now I live a real life without the structure of the fantasy and the failure and everything so linear and all tied to how much I ate in a day. Now I live a much more complicated life. It’s a more full life, but I miss the simplicity sometimes. I miss the goals. I miss not having to think about it so much. So I have sympathy for myself and everybody else who still does this because it’s not just about the desire to lose weight. It’s about that cycle as well.

I don’t have something that promises me a perfect future 30 pounds from now anymore, but that’s okay because that’s not a sustainable pattern, and that wasn’t getting me anywhere. That was keeping me stuck in limbo for a really long time, and now I live in the reality of day to day, which is sometimes great and sometimes shitty and sometimes boring, but it’s real. It’s the real deal.

Do you think the Internet makes it harder to remain sane about food? For example, your book describes feeling overwhelmed with options when you order from Seamless, and you recount Internet trolls making you self-conscious.

What has the Internet not affected in our lives? It makes everything better and worse, doesn’t it? I think the Internet has really fetishized food even more. We have all these food channels, and we have this crazy bacon obsession. It’s very extreme: “Oh my God, the bacon bonanza and the pork belly! What’s the most fatty, decadent thing I can eat?” versus “CLEANSING!” Social media has fed into that. I always want to take a picture of my sandwich. Every time you do that, you’re making food more than food. It took me a really long time to recognize that as maybe not the healthiest impulse.

Is loving food just as destructive as fearing it, then?

There’s a difference between loving food and having your life centered on it — because, man, there are those meals that really are special, and sometimes you have that life-changing burger or that thing your mom used to make that you’ll always remember from childhood. That is a normal and very okay thing to have in your life. But there’s a difference when every food has that intense vibration, when it stands out and you can’t just pick up an apple and eat it because that’s what you’d like to eat right now.

So, yes, I think you can love food and not be obsessed with it. I still have foods that I absolutely love. I’ve even written about the “food porn” Instagram. You have to define the line for yourself, but there are times when it’s perfectly acceptable to be like, “Look at this goddamn beautiful cake I made” or “This pasta is wowing me.” Food is part of our lives, and we should celebrate it, but we have to be conscious about what we’re doing.

What other advice would you give people who want to develop a healthier relationship with food and their bodies?

For starters, it’s always good to get some help if you can, at least in the beginning. If I just did this myself, I wouldn’t have been held accountable. I needed somebody to remind me what I was doing, to remind me to trust myself. Whenever you feel alone, things are a lot more painful and harder to commit to.

Help is available, even if it’s just picking up the Intuitive Eating book and going online to an intuitive eating community. While there’s a “pro-ana” community that people rely on to maintain their commitment to anorexia, there’s a much bigger and healthier community around body positivity. But you have to seek it out because you’re not just going to turn on the television and see body-positive representations.

I’m certainly not the only one talking about these things. There’s plenty of people of all shapes and sizes and genders and backgrounds. So make an effort to immerse yourself in literature and blogs and people and a culture that support what you’re doing.

If you could go back in time and talk to the version of yourself that was still dieting, is there anything you would say to spare yourself the pain of learning all these things the hard way?

I think about that sometimes, but at that time I probably wouldn’t have been ready to hear it and would have just rejected it. It would be amazing, though, if I could have just shaken my shoulders and said, “You think your life’s going to change with this diet, but really, nothing is going to change until you stop this. Until you really, really stop this.” I wasted so much of my life treading water in this cycle and feeling like I couldn’t do anything until I fixed this problem that was my body. If I could, I’d tell myself, “Just go out and start your career and date people and live your life. Don’t wait until anything. Don’t wait.”

Shares