He laughed.

It was Oct. 5, 1982, and "E.T." was the No. 1 movie in America. John Cougar Mellencamp’s “Jack and Diane” was blasting on every radio from Texas to Indiana. And in a press briefing at the White House, Reagan’s press secretary, Larry Speakes, laughed. A reporter, Lester Kinsolving, asked Speakes if he had any comment about the 853 people who had died from “AIDS,” a mysterious illness recently classified by the Centers for Disease Control as an “epidemic.” The disease was still so new in the public consciousness that when posing the question, Kinsolving spells the acronym out “A-I-D-S,” rather than saying ayds.

To highlight the severity of AIDS, Kinsolving referred to it as the “gay plague.” “It’s a pretty serious thing,” he said. “Over one in every three people who get this have died, and I wonder if the president was aware of this?” “I don’t have it,” Speakes chuckles. “Do you?”

That laughter would stand in place of silence. If Speakes brushed off the hundreds who had died from AIDS, that became the unofficial policy of his boss’s administration. Ronald Reagan wouldn’t publicly speak out about AIDS until a press conference three years later, when he was asked about federal funding for HIV research. Just over two weeks after, Rock Hudson passed away after collapsing at Paris’ Ritz Hotel. A note from the first lady, whom Hudson knew from their Hollywood days, could have prolonged his life by transferring the 59-year-old actor to a military hospital specializing in experimental treatment. But Mrs. Reagan refused to get involved, all but leaving her old friend to die.

***

If you know anything about Reagan’s involvement in the 1980s AIDS crisis, surely you know that he and his wife were no friends to the gays, ignoring the problem while millions died in the streets. When Hudson died on Oct. 2, 1985, the community was akin to a mass grave. But maybe you don’t. Hillary Clinton apparently didn’t. During an MSNBC interview conducted before she spoke at Nancy Reagan’s funeral, Clinton credited the late first lady’s “low-key” activism in “starting a national conversation when before nobody would talk about it, nobody wanted to do anything about it.”

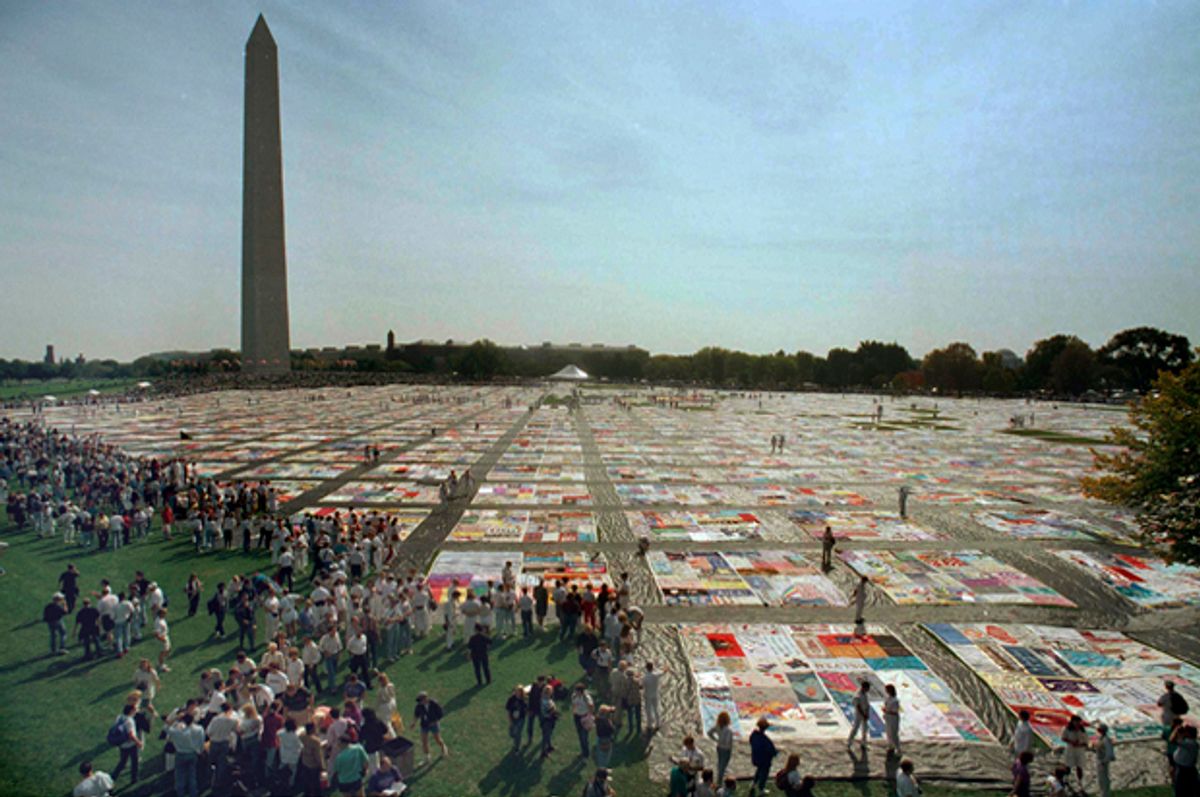

To say that her comments broke the gay Internet would be an understatement. The former secretary of state may as well have ripped it apart with her bare, perfectly manicured hands. The backlash was so severe that Clinton issued not one but two apologies in the subsequent days. In an initial tweet, Mrs. Clinton claimed that she merely “misspoke.” In a Medium post, the candidate further elaborated her position. “To be clear, the Reagans did not start a national conversation about HIV and AIDS,” she wrote. “That distinction belongs to generations of brave lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender people, along with straight allies, who started not just a conversation but a movement that continues to this day.”

To make that kind of error isn’t just a mistake. It dangerously rewrites the history of the AIDS epidemic in favor of the oppressors. It’s disgusting and horrifying, but in a way, it was unsurprising. “She was part of a Democratic establishment in the 1980s that was by and large as out of touch with the plight of HIV/AIDS and LGBTQ people as the Reagan administration was at the time,” Vox’s German Lopez wrote. “So it's wholly plausible that her recollection of the period genuinely reflected well on the Reagans, at least on this issue.”

But if Clinton’s position of privilege reflects her own ignorance on the lived experiences of the men and women living with AIDS, it also highlights something equally troubling: Very few Americans—whether queer or heterosexual—know all that much about LGBT history. A 2009 survey from Newsweek showed that a majority of U.S. citizens didn’t know even basic facts about American government—like what the Constitution does—so the problem is that we don’t know anyone’s history. However, this phenomenon is especially dangerous for LGBT people—because without educating ourselves our cultural legacy, it allows others to use our own history against us.

A glaring example of this reared its ugly head during the recent Oscar ceremony, when Sam Smith won the trophy for best song for his Bond tune, “The Writing’s on the Wall.” In his speech, he infamously suggested that he was making history. “I read an article a few months ago by Sir Ian McKellen, and he said that no openly gay man had ever won an Oscar,” Smith said. “If this is the case—even if it isn’t the case—I want to dedicate this to the LGBT community all around the world.”

Sam Smith would later learn that he did not, in fact, shatter the glass ceiling for gay men at the Oscars. That honor belongs to Howard Ashman, who won two Oscars in Smith’s same category (for “The Little Mermaid” and “Beauty and the Beast”). The very same evening, a reporter informed Smith of this, and he inserted his foot all the way down his throat. “I should know him,” Smith joked. “We should date.” Ashman died of AIDS in 1991.

Call his remarks what you will—either deeply regrettable or the product of deluded narcissism—but they’re also indicative of the widening “gay generation gap” in the LGBT community, in which many young queer people coming of age today know very little about those who bravely fought for the rights they now enjoy. If Sam Smith is unaware of who Howard Ashman is, would you expect him to know about Miss Major or Marsha P. Johnson, the pioneering trans activists who helped lead the Stonewall Riots? For that matter, would you expect Hillary Clinton to?

In a New York magazine essay six years ago, Mark Harris argued that the community was deeply divided between the generations that were shaped by the experience of the HIV crisis and those who came later, many of whom weren’t even born during the Reagan administration. If previous generations shared their history through culture—or what Harris calls the “(sub)cultural iconography” that ranges from Judy Garland to "All About Eve"—older gay men feel as though the millennial gay experience is not just ahistorical. It’s at the expense of their own legacy, acting as a kind of cultural erasure.

“For most of them, AIDS is not their past but the past,” Harris wrote. “No wonder some of us feel frustrated; when we complain that young gay men don’t know their history, what we’re really saying is that they don’t know our history—that once again, we feel invisible, this time within our own ranks.”

Today, queer experience is both more connected and less so than ever before. Through apps like Grindr and Scruff, young LGBT people have the ability to get to know each other on an unprecedented global scale, but these experiences often promote insularity as much as they do connectivity. When you can meet someone through your phone, there’s less of an incentive to go out to a bar, meet others around you, or get to know those who have come before you. In 2016, you can just google Bayard Rustin, but the problem is that many won’t.

In a series of tweets after Smith’s Oscar win, screenwriter Dustin Lance Black reminded us that we “stand on the shoulders of countless brave men and women who paved the way for us.” Just seven years before Sam Smith was able to add “Oscar-winner” to the front of his name, Black earned a little gold statuette for “Milk,” the 2008 biopic about Harvey Milk, the first openly gay man elected to political office in California. The Guardian’s Owen Jones argued that preserving the legacies of leaders like Milk, Cleve Jones and Peter Staley “encourages us to continue in their tradition to overcome all forms of oppression and prejudice.”

But the real lesson here is that what our queer forebears fought for isn’t over. If not, no one would ever, ever confuse the Reagans for the queer community’s saviors. It’s hard to believe that a politician seeking the highest office in the land would be responsible for such a galling gaffe, but what’s equally worth pointing out is that—until the Internet corrected her—many queer people likely wouldn’t have known there was anything wrong with her comments.

Unless LGBT people start to educate our community—especially its youth—about our history, it’s men like Larry Speakes who will have the last laugh.

Shares