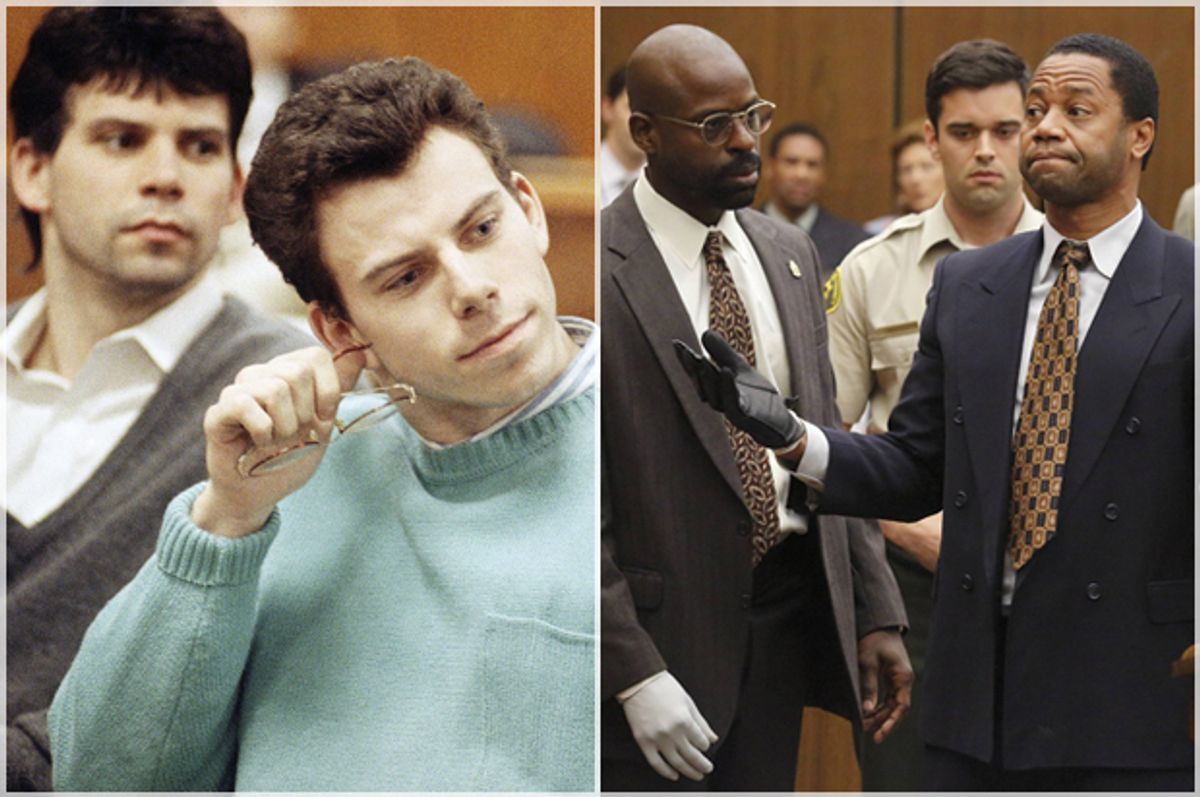

Late yesterday, in an announcement that probably could have been predicted and recited in chorus by anyone following television news, CBS announced that it ordering a true-crime anthology miniseries on the JonBenet Ramsey case, following the 20-year anniversary of the 6-year-old’s disappearance and murder. The announcement comes just a day after NBC ordered its own true-crime anthology miniseries, on the Menendez brothers, convicted of murdering both their parents and nearly getting away with it. And it comes just two days after the brilliant conclusion to FX’s “The People V. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story,” which closed with equally brilliant ratings for the cable network.

We are seeing the convergence of two trends—albeit two closely related trends—which together, studios hope, will snag viewers’ attention even more potently. The first is the anthology miniseries trend—not a new format for television, but one that FX and creator Ryan Murphy revived with “American Horror Story,” in 2011. The second is true-crime—an even less original trend, to be sure, but one that has chewed out increasingly more space in the national conversation.

Campy true-crime has never really disappeared from television; “Dateline NBC,” “Unsolved Mysteries,” and the entire programming lineup of networks like Investigation Discovery have been producing, with maximum schlock, tales of horror from middle America. From Lifetime’s re-enactment films to “Law & Order”’s “ripped from the headlines” episodes—from “Judge Judy” to “Divorce Court,” even—the national fascination with crimes from seemingly next door, in a system we all live in and perpetuate, has never gone anywhere.

But the popularity of the podcast “Serial,” hosted by “This American Life” alum Sarah Koenig, changed what true-crime could be—at least in the minds of network executives. Where true-crime was usually splashy and exploitative, “Serial” was thoughtful and journalistic; where the “characters” were often stereotypes or caricatures, Koenig’s interviewing and research created complex figures—anchored, of course, by phone calls with convicted murderer Adnan Syed himself.

"Serial" was quickly followed up by HBO’s “The Jinx,” which went, incredibly, even further. Not only did the filmmakers, led by Andrew Jarecki, make Robert Durst into an approachable, and even sympathetic figure, they also did what law enforcement couldn’t — “The Jinx” found new evidence that led to the case being reopened. “Serial” whetted the prestige audience’s appetite for a quest for truth. “The Jinx” found a way to actually feed it, with one of the more stunning miniseries finales I can remember.

At that point, you could almost hear networks scrambling to find new crime stories. Netflix, for example, put up its “Making A Murderer,” and FX produced the aforementioned “The People V. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story.” Both were hits, though “Making A Murderer,” to my mind, is a lot less satisfying than “The People V. O.J. Simpson.” But that’s at least some of the explanation for why we’re now facing re-enactment after re-enactment of long-abandoned crimes that captured the public’s imagination.

The other, naturally, is “True Detective.” “American Horror Story,” the first of this spate of anthology miniseries, is a special, once-brilliant show. But “True Detective”’s first season was a phenomenon not unlike “Serial” or “The Jinx.” And much of that season’s success, I think, came not just from stand-out protagonist Rust Cohle (Matthew McConaughey) or showrunner Nic Pizzolatto’s weird brush with genius, but with the season-long drive to solve a crime. “Fargo,” also on FX, was not about solving a case (we knew whodunit from the first episode) but more about struggling with evil; “American Horror Story” was not about crime at all.

But in all of this, studios learned something fundamental about their audiences that they seemed to forget in the glut of prestige television — viewers like to get to a well-structured end of a story, after a time investment that is neither barbarically long nor criminally short. Six to 12 hour-long episodes seem to be a sweet spot for audiences interested in “Serial,” “The Jinx,” and “True Detective.”

And real-life tabloid crime seems to be the most engrossing of all. "Making A Murderer" and "Serial" depicted real-life crimes like the small-town scandals of the fictional "True Detective," "Fargo," and "American Crime." In the arena of true-crime cold cases, though, "The People V. O.J. Simpson: American Crime Story" went for the metaphorical jugular—the trial of the century, a tabloid-cover, primetime-news, mass media phenomenon that rocked the nation. This isn't just about solving a crime, this is about examining, with the lens of either nostalgia or critique, the way a media narrative filtered through a nation. JonBenet Ramsey's case, and the Menendez brothers' story, are other examples of this. Even though Casey Anthony and Amanda Knox got their own Lifetime made-for-TV movies already, cases like theirs may not be far behind as studios scramble to duplicate the cocktail of voyeuristic nostalgia, high production values, and true-to-life thrilling scandal that audiences have taken to.

Et voilà, here we are. True-crime anthology miniseries are, according to ratings math and studio logic, exactly what viewers want to see. So now, we are going to see a lot of them. I am curious, but also a little bit skeptical of any copycat trend, which is likely to create a lot of lesser iterations of the same. It will be interesting to watch networks realize that it is not format or topic that really indicates a show’s merit, but that other, elusive, essential metric: quality.

Shares