Livy had some choice advice for her husband, Mark Twain: Make it less funny. Give the audience a chance to catch its breath.

Never a champion of his vaudeville tendencies, she now wanted him to show off his narrative talents. Lesser men could tell that christening joke; she suggested that he insert at least one long, moving emotional story into his program, maybe Huck Finn and runaway slave Jim on the raft floating down the Mississippi. He could build to the key scene when the poor undereducated white boy, the hooligan son of the town drunk, agonizes over whether to do what everyone in Hannibal tells him is the right thing to do, that is, to hand over his best friend, Jim, to the slave catchers. Huck, in that moment, must decide whether to ignore his heart and obey the community “conscience” and the laws of the slave state of Missouri. It is immensely powerful in the midst of a novel, but would it work as a twenty-minute monologue?

Twain was skeptical, but he took her advice in Minneapolis, the sixth stop of the tour, and that Huck-and-Jim story would prove far and away the most popular of his round-the-world repertoire, singled out by critics and audiences from North America to New Zealand to India.

But before he could deliver in Minneapolis, he had to weather the fifth stop, Duluth, which had played out like a comedy of errors. The gargantuan steamship SS Northwest had hit a traffic jam of 600 boats waiting at the locks connecting the unequal water levels of Lake Huron and Lake Superior, and that delay had caused 1,250 paying customers to wait an hour in 100-degree heat in the unventilated First Methodist Church. Major Pond had shouted at the dock to the panicked church organizer:

“Don’t worry, we’ll have ’em convulsed in ten minutes.” When Susy later heard about Pond’s slick promise, she wondered how “poor little modest mama” was able “to put up with such splurge.”

After some mix-ups in baggage transfers and unbooked sleeping cars, the Clemens entourage arrived, exhausted, in Minneapolis on the morning of Tuesday, July 23. Pond checked them into the city’s finest, the eight-story West Hotel, so luxurious that it charged $5 a night per person, while other excellent places in town charged $2. (It’s a tad ironic that Twain, trying to escape bankruptcy, almost always stayed in each city’s best hotel; he seemed determined never to lower his heiress wife’s standard of living.)

Minneapolis in 1895 was a fast-expanding commercial metropolis of 200,000 “including many Scandinavians,” parked on the Mississippi River, harnessing “the power of 120,000 horses” at St. Anthony Falls to run flour and textile mills. Pillsbury produced more fine-grade flour than any other mill in the world, with quality equal to the “best Hungarian fancy brands,” according to the Baedeker guide. Lumber mills north of the city band-sawed 400 million board feet of pine and hardwood logs a year. Prosperity attracted investment from East Coast enterprises, such as New York Life Insurance, whose building featured a famous French-inspired double-spiral staircase.

Major Pond had also booked Twain to have lunch with the mayor and other prominent citizens at the Commercial Club. A newspaper reporter claimed he overheard at least fifty people inform the author that "Innocents Abroad" was the first book they had ever read. In every city, celebrities attracted invitations. The author endured the glad-handing, but he admitted in his notebooks that he often found small talk very small, and preferred an audience of one thousand strangers to an audience of one stranger.

Twain was fagged out after the night train and chitchat, and his thigh was hurting. He begged off for an afternoon nap. Major Pond woke him to talk to six reporters. He refused to get out of bed, so the reporters interviewed him there, still under the covers.

He liked self-promotion but hated interviews; he even crafted a comedy segment—that he performed about a dozen times—on how to baffle interviewers with mounds of contradictory answers. He would cite three birthplaces; he would claim he was a twin and that he wasn’t certain whether he or his brother had drowned. He’d say a birthmark might prove it, but he wasn’t sure which twin had the birthmark. “There it is on my hand,” he would say, confessing that he must have been the twin that drowned.

Being a former newspaperman, he expected to be misquoted. He also hated giving away material for free and loathed how reporters summarized and bollixed his stories. He would attend a banquet, make some remarks, and then read his quotes in the next day’s paper. “You do not recognize the corpse, you wonder is this really that gay and handsome creature of the evening before.”

But when those six reporters entered Room 204 of West Hotel, Twain charmed them. He explained about the carbuncle forcing him to stay in bed; he discussed some of his favorite living authors (William Dean Howells and Rudyard Kipling); he told a cute family story about how his then nine-year-old daughter Jean had once tried to jump into an adult conversation. “I know who wrote Tom Sawyer,” Jean chimed in. All the dinner guests stared at the little girl. “Mrs. Harriet Beecher Stowe did!”

And the author waved the American flag, saying he was ending his four years of living in Europe. “I am going to settle down in my Hartford home and enjoy life in a quiet way.”

As always, Twain addressed the reporters, as he spoke to friends, in a s-l-o-w manner with his mesmerizing voice with a hint of a twang, similar to his stage performance.

His talk—I encountered him several times in London and New York—was delightfully whimsical and individual. The only drawback was that his natural drawl—freely punctuated, moreover, by his perpetual cigar being constantly put into and taken out of his mouth—made his utterance terribly slow. While waiting in a faithful and always justified hope that the point would come, you were reduced to admiring his magnificent head, leonine, with a snow-white mane.

So wrote Anthony Hope (1863–1933), English author of the huge 1894 bestseller "The Prisoner of Zenda."

At the agreed cut-off time, Major Pond burst into the room. A scribe was just asking Twain if he had ever visited the city, and he replied that he had, eleven years earlier. Pond chirped: “Why, I was in Minneapolis when there were no saloons here.”

Twain drawled: “Well, you didn’t stay long.” The newspapermen “laughed at the major’s expense.”

Twain rested and continued to memorize the new material.

Around 7:30 p.m., he and Pond took the short walk to the Metropolitan Opera House along sidewalks paved with thick cedar slabs. The ornate opera house was packed from the orchestra seats to the top gallery, with captains of industry and children, college students and mill workers. Twain attracted a diverse crowd. The Minneapolis Times, in its scene setter, estimated that no living American had made more people laugh than Mark Twain, especially in the wake of “the untimely death of Artemus Ward.”

As he had put in his first flyer: “The trouble begins at eight.” At the stroke of the hour, he strode out in the “swallow-tail [jacket] and immaculate shirt-bosom of fin-de-siecle society.” One reviewer marveled at his transformation from the rough miner and suntanned riverboat pilot of the 1860s. The Times entitled its piece “Twice Told Tales” because for the most part Twain was telling his greatest hits.

Twain waited for the applause to die down, then said simply: “Ladies and gentlemen, with your permission, I will dispense with an introduction.” More applause greeted him. (He was casting off that rambling “Morals” speech.)

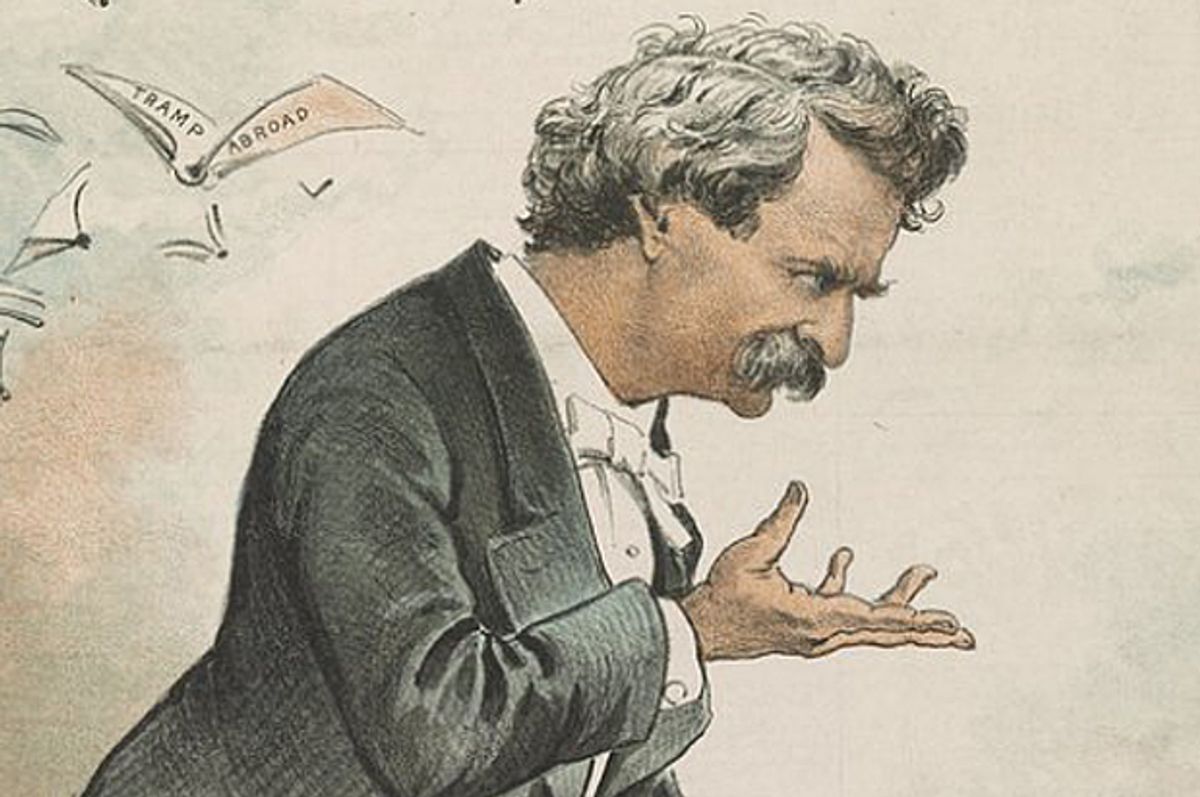

He stood there, bushy brows, mustache and thick wavy hair—a caricaturist’s delight—with the merest, faintest rumor of a hint of mischief in the eyes. He spoke slowly, not loudly, but his rich voice carried in an intimate way. He never smiled, seemed startled that anyone would laugh. Many claimed that hearing him topped reading him, a high bar indeed. (No recordings exist of Twain’s performance or even of his voice; he feared he’d miss out on a payday if someone started making copies on Edison wax cylinders and selling them.)

He launched right into his first story. (The Minneapolis Times noted pauses and laughter.)

A man ought to know himself early—the earlier the better. He ought to find out . . . how far he can go and how much bravery there is in him and when to stop—not overstrain. I had the good fortune to learn the limit of my personal courage when I was only thirteen. My father at that time was a magistrate in Hannibal, Missouri.

Twain explained that his father was also the town coroner and that he kept a little bird-coop-sized office with a sofa.

Often when I was on my way to school I would notice that [the sky] was threatening; that it was not good weather for school (laughter) and very likely to get wet and I better go—fishing (laughter), so I went fishing. It was wrong—yes, it was wrong. That is why I did it. Forbidden fruit was just as satisfactory to me as it was to Adam. If he had been there he would have gone a-fishing.

I always had more confidence in my own judgment than I did in anybody else’s. And now when I returned from those unorthodox excursions it was not safe for me to go home, for I would be confronted with all sorts of ignorant prejudice. (laughter)

And so I used to spend the night in that little office and let the atmosphere clear it (laughter).

Twain recounted that one day in Hannibal, while he was off fishing, a street fight had broken out. A man had been stabbed in the chest with a Bowie knife and killed, and his corpse—stripped to the waist—had been dragged to his father’s office for an inquest the following morning.

Well, I arrived about midnight (laughter) and I didn’t know anything about that (laughter), and I slipped in the back way and groped around until I found that [sofa], and laid down on it, and I was just dropping off into that sweetest of all slumbers, which is procured by honest endeavor. (laughter) When my eyes became a little more accustomed to the gloom it seemed to me that I could make out the vague, dim outline of a shapeless mass stretched there on the floor, and it made me uncomfortable. My first thought was to go and feel of it—and then I thought I wouldn’t. (laughter) Well, my attention was carried away from my sleep. I was just beyond that thing.

Twain decided to wait till the moonlight through the window revealed the object.

But it got to be so dreary and so uncanny and sort of ghastly— waiting on that creeping moonlight, and that mystery grew and grew and grew in size and importance all the time and it got so that it didn’t seem to me that I could endure it. And then I had an idea. I would turn over with my face to the wall and count a thousand (laughter) and give the moonlight a chance (laughter).

He made it as high as forty-five, drifted off a few times, whirled a few times, and then the next time, he saw a “pallid hand” in a square of moonlight.

I sat right up and began to stare at that dead hand and began to try—to say to myself “Be quiet, be calm, don’t lose your nerve” (laughter). So I did the best I could and watched that moonlight creep, creep, creep up that white, dead arm, and it was the miserable, miserable . . . —I never was so embarrassed in my life (laughter). It crept, crept, crept until it exposed the whole arm and the white shoulder and a projecting lock of hair—it got so unendurable that I thought I must begin to do somethin’ some time or other, some how or other.—I closed my eyes, put my hands on my eyes and held them as long as I could stand it, and then opened them. And then I got just one glimpse, just one glimpse and there was that drawn white face, white as wax in the moonlight, and staring glassy eyes, the mangled body. . . . Just that one swift glimpse and then, well, I went away from there (laughter).

I did not go in what you might call a hurry—I just went (laughter) that is all. I went out the window (laughter). Took the [curtain] sash with me (renewed laughter). I didn’t need the sash but it was handier to take it than it was to leave it (laughter) so I took it.

Ten minutes in and Twain was off to a very good start. He now made no pretense of using “Morals” to bind the stories together. He simply said, with absolutely no basis for saying it: “Now that brings me by a natural and easy transition to Simon Wheeler.” He then told “Jumping Frog,” which he had whittled down to thirteen minutes, and then “Grandfather’s Old Ram,” drawn from Roughing It. The brilliant punch line is that there is no punch line; the meandering storyteller veers off again and again. “My grandfather was stooping down in the level meadow, with his hands on his knees, hunting for a dime that he had lost in the grass and that ram was back yonder in the meadow when he sees him in that attitude he took him for a target . . . and came bearing down at twenty miles an hour.” The story hinged on the teller always getting sidetracked and never revealing whatever happened to the old man and the ram. By the end, he had some audience members gasping for air.

Now Twain followed Livy’s advice. Even though his comedy was flourishing, he sought the downbeat and told Tom and Huck. He needed an adept introduction to place listeners who hadn’t read the book smack in the middle of the drama.

And that brings me by the same process which I am following right along, regular sequence morally, and to an incident which made a great deal of stir at the time when I was a boy down there in [Hannibal], a sort of thing which you cannot very well understand now; that was the loyalty of everybody, rich and poor, down there in the South to the institution of slavery, and I remember Huck Finn, a boy who I knew very well, a common drunkard’s son, absolutely without education but with plenty of liberty, more liberty than we had, didn’t have to go to school or Sunday school, or change his clothes during the life of the clothes, and we preferred to associate with him because we envied him. Even Huck Finn recognized and subscribed to the common feeling of that community; that it was a shame, that it was a humiliation, that it was a dishonor, for any man when a negro was escaping from slavery—it was his duty to go and give up that negro. It shows what you can do with a conscience. You can train it in any direction you want to. I have written about that in a story where Huck Finn runs away from his brutal father and at the same time the slave Jim runs away from his mistress [i.e., owner], because he finds she is going to sell him down the river, and they meet by accident on a wooded island and they catch a piece of raft that is adrift and they travel on that at night, hiding in the daytime and they float down the Mississippi.

Now Twain needed to act out the scenes on the raft. He had marked up his own copy of Huck Finn, crossing out words, adding underlines for emphasis, and colloquial bridges. He even marked when to “blubber” or “bellow.”

So, he described how Huck and Jim were approaching the “free” town of Cairo, Illinois, but Huck’s conscience was troubling him.

That was where it pinched. Conscience says to me, “What had poor Miss Watson done to you that you could see her nigger go off right under your eyes and never say one single word? What did that poor old woman do to you that you could treat her so mean? Why, she tried to learn you your book, she tried to learn you your manners, she tried to learn you to be a Christian. She tried to be good to you every way she knowed how. That’s what she done.” I got to feeling so mean and treacherous, and miserable I most wished I was dead.

Then Twain described how Jim made Huck feel even worse because he told him that when he was free, that if he couldn’t buy his children, he’d get an abolitionist to go steal them.

It most froze me to hear such talk. It was awful to hear it. He wouldn’t ever dared to talk such talk in his life before. Here was this nigger, which I had as good as helped to run away, coming right out flat-footed and saying he would steal his children—The children didn’t belong to him at all. (Laughter.) The children belonged to a man I didn’t even know; a man that hadn’t ever done me no harm.

Huck is torn and goes off in a canoe, maybe to tell on Jim, but as he’s paddling away, he hears the runaway slave yell:

“Dah you goes, dar you goes, de ole true Huck; de on’y white genlman dat ever kep’ his promise to ole Jim.” Oh, when he said that, it kind o’ broke me all up.

Then Huck runs into a boat full of slave catchers. And one asks him:

“What’s that yonder?”

“A piece of a raft,” I says.

“Do you belong on it?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Any men on it?”

“Only one, sir.”

“Well, there’s five niggers run off to-night up yonder, above the head of the bend. Is your man white or black?”I tried to say he was black but the words wouldn’t come. They hung fire and I seemed to hear that voice. I did not hear it at all, but it seemed just as natural as anything in the world, that voice a-saying “You true Huck. you only fren’ left Jim now.”

There was my conscience tugging after me all the time. It kept saying that anybody that does wrong, goes to the bad place [i.e., Hell]. It made me shiver and then I says “I don’t care anything about it. I will go to the bad place. I will take my chances. I ain’t going to give Jim up. And then I says, “The man on the raft is white.”

And then he says, “It took you a good while to make up your mind what his color is. I reckon we’ll go and see what his color is.”

Twain has been acting out the voices: the boy, the slave, the men. The Minneapolis auditorium was dead silent, waiting. He slips back into Huck’s voice.

Well, I was up a stump, I got to lie . . . Just in ordinary circumstances truth is all right but when you get in a close place you can’t depend on it at all. So I had an idea and I says: “It’s pap and he

is sick, and so is Mary Jane and the baby and pap will be powerful thankful for you will help me tow the raft ashore. I have told everybody before and they have just gone away and left us,” and he says, “That’s mighty mean!” And the other says, “Mighty bad, too.”“What is the matter with your father?” “He is all right; it ain’t catching.”

“Set her back, John. Keep away, boy, keep to leeward. Confound I just expect the wind has blowed it to us. Your pap’s got the smallpox and you know it precious well. Why didn’t you come out and say so? Do you want to spread it all over? Good-bye, boy. You put twenty miles between us just as quick as you can. You will find a town down the river—tell them the family have got the chills and fever. Everybody got that down there. Don’t you tell them, they have the small-pox. Good-bye, boy.”

“Good-bye, sir,” says I. “I won’t let no runaway niggers get by me if I can help it.”

The audience applauded, and over time as Twain realized the power of the story he expanded it and acted out Huck blubbering, begging the men to come help his sick family, all to make the lie more convincing.

And he would also work on sharing the moral while trying not to sound preachy. He would refine the introduction to include this pithy phrase: “In a crucial moral emergency a sound heart is a safer guide than an ill-trained conscience.” Reread that line. Somehow, this concept seems to go to the essence of all Mark Twain’s writings and beliefs. Forget the conventional wisdom, the current laws or religious teachings, try to follow the “sound heart” of a boy or youngster.

The message resonated. Audiences in Timaru, New Zealand, and Rawalpindi, India, applauded long and loud, and in the mill town of Minneapolis, Minnesota. “I am getting into good platform condition at last,” he wrote to H.H. the next morning. “It went well, went to suit me here last night.”

Twain told a few more stories, even gave a brief encore anecdote; then he bowed, soaked up the applause, and remained standing there center-stage for a long time as the house emptied. It was as though, at least in that triumphant moment, the financial woes and horrible stress of relearning his craft were finally melting away.

Major Pond wrote in his diary:

It was about as big a night as Mark ever had, to my knowledge. He had a new entertainment blending pathos with humor, with unusual continuity. This was at Mrs. Clemens’ suggestion . . . the show is a triumph.

Twain now began filling his notebooks with speech ideas and travel observations. His leg healed. As he fine-tuned his delivery over the next few cities, he began to receive louder, longer ovations and even more effusive daily tributes in the newspapers. Editorials were sympathetic. He might have dreaded the platform, but he didn’t dread the praise. As he once wrote to his youngest daughter: “I can stand considerable petting. Born so, Jean.”

Excerpted from "CHASING THE LAST LAUGH" by Richard Zacks. Copyright © 2016 by Richard Zacks. Excerpted by permission of Doubleday, a division of Penguin Random House. All rights reserved.

Shares