Sell your home at a loss and Congress says tough luck. Whether you paid too much or the market collapsed, it’s a personal loss and you get no tax deduction. The loss is 100 percent yours and yours alone.

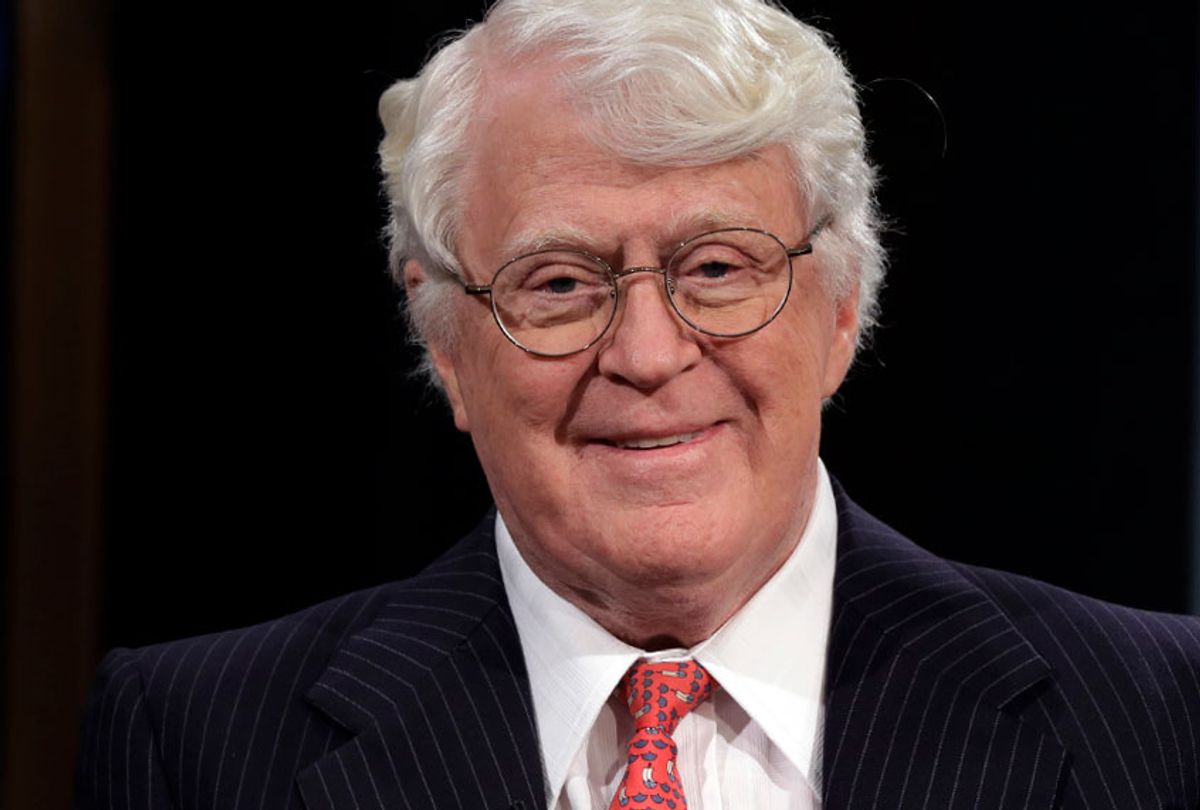

In this fourth installment of The Koch Papers, we’ll look at Bill Koch’s purchase of an estate to expand his Cape Cod vacation home and a deduction he then took on his personal income tax return. The case raises questions about the diligence of federal tax law enforcement and whether under the Trump administration the IRS shows favoritism to Trump supporters.

William Ingraham Koch wanted to expand his Cape Cod vacation home compound, a lavish estate where he hosted a 2016 campaign fundraiser for Donald Trump. The Florida billionaire, whose primary home is in Palm Beach six blocks from Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort, wanted the neighboring 26-acre estate so much that, The Koch Papers show, he paid more than twice the $29.5 million appraised value of the property.

The total amount he deducted? $42,637,729.

The price Bill Koch paid? $63,744,920.

How did Koch deduct two-thirds of the value of a personal residence? The key was buying the property not in his own name, but through a Limited Liability Company or LLC. Another key is that the IRS, which is focused on income. It doesn’t normally look at real estate ownership records.

The purchase added 26 acres to Koch’s existing property, including a peninsula that gave him increased privacy. The purchased property a magnificent 7,000 square foot home, more than a thousand feet of waterfront with a beach house, tennis courts and extensive gardens.

Sotheby’s, in a brochure, called the property Koch bought “One of the most significant parcels on the entire East Coast.” The 2013 Cape Cod real estate deal was widely reported in publications covering real estate and Boston area business.

Koch deducted all of the $34.6 million premium he paid for the neighboring property. Then he deducted another $8 million, the Koch Papers show. He did this even though Congress has enacted laws that explicitly deny losses on personal residences.

The IRS was told of this apparently illegal deduction in May 2018, in a whistleblower complaint filed by Charles Middleton, the former chief tax executive for Koch’s company, Oxbow Carbon LLC. Middleton and his office prepared both the company’s and Koch’s personal tax returns.

Middleton called the losses taken on the Cape Cod vacation home tax fraud.

Koch’s spokesman, in a statement, said “It is not Mr. Koch’s personal residence. It was an investment property.”

That position shows how Congress needs to hold hearings on the rules barring losses on personal residences. By using S corporations to acquire homes where one lives, including neighboring properties whose purchase would expand an existing vacation home compound, taxpayers could easily get around the rules prohibiting losses on personal residences.

Middleton told the IRS that the sale price, tax deduction and other amounts in his complaint were “all set forth in spreadsheets and PowerPoint documents prepared by Oxbow’s tax department.”

There is no indication the IRS followed up on Middleton’s 2018 complaint. A prior complaint filed during the waning days of the Obama administration about other Koch tax avoidance strategies sparked an IRS criminal inquiry, the Koch Papers show, but the IRS appears to have closed the investigation shortly after Trump took office in 2017.

Hidden documents

Middleton told the IRS in his 2016 complaint about an arrangement under which profits earned by Koch’s Oxbow Carbon LLC were reported as profits earned in the Bahamas. He also told the IRS that key documents were hidden from the IRS during an audit of the 2011 and 2012 tax returns of both Koch and his Oxbow Carbon LLC.

Koch and his company, in a statement, said the IRS closed the audits without making any changes. The company said it fired Middleton for cause. Middleton says he was fired after discovering documents were withheld from the IRS and reporting this to Bill Koch.

Since Congress denies tax losses on personal residences, other taxpayers could reasonably expect the IRS to investigate. But Middleton’s lawyers say that five months after Trump took office the IRS stopped communicating with them. William Cohan, the Rancho Santa Fe, Calif., tax litigator who is Middleton’s main lawyer, said the IRS has never responded to the 2018 complaint, the one that includes the claim of improperly deducting the loss on the Cape Cod vacation home purchase.

Normally, the IRS only looks at the past six years of tax returns unless fraud is involved. There is no statute of limitation on tax fraud. The tax return on which the deductions for the Cape Cod vacation home expansion were taken was filed less than six years ago.

State tax issues, too

The losses may also invite scrutiny by the Massachusetts Department of Revenue of both Koch’s actions, including whether property tax laws were violated, and the taxes of the seller, socialite Rachel “Bunny” Mellon, an heiress to the Listerine mouthwash fortune and widow of Paul Mellon, the art collector. The widow, a noted horticulturist who was 102 at the time of the sale, died a year after the sale.

Like our federal government, Massachusetts does not allow tax deductions for losses on personal residences. It does tax gains on residential sales with some exceptions that are not relevant here.

Significantly, Koch didn’t even sell the property on which he took the deduction. Instead, he used a tax gambit involving a widely used type of corporation, the LLC.

He bought the Mellon property through Indian Point LLC, which Koch declared to be an S corporation, according to Middleton. Then Koch liquidated Indian Point, in effect closing it. When a business is closed down all of the internal gains and losses have to be taken into account.

Because of the accounting rules for such liquidations Koch had to report a gain of $8,819,817 on land that was undervalued. But he then more than offset this gain by reporting the more than $42 million loss. The loss represented the difference between the more than $63 million he paid for the property and the close-out value, which Koch reported as $19.5 million, Middleton told the IRS.

The net tax effect of what Middleton told the IRS was “the improper position” Koch took on his personal tax return…a tax benefit worth $8 million.

The way the IRS operates, employees, pensioners and investors have very limited opportunities to cheat because all of their income is independently verified by employers, retirement plan administrators and investment firms.

But Congress trusts owners of LLCs and other businesses to report income in full without verification. Reports by the IRS, by its Taxpayer Advocate, by the Treasury Inspector General for Tax Administration, by the investigative arm of Congress and by journalists including me have shown that unverified income results in vast opportunities to understate income and overstate deductions. Yet Congress has done nothing to correct this except to add stock and mutual fund investment gains to the income verification regime, a change I and a few others urged.

Business owners like Bill Koch and Trump still benefit from not having their incomes independently verified.

Using corporations instead of owning property directly can also be used to assert tax benefits, as the statement issued by Bill Koch’s spokesperson shows. The statement raises questions about whether individuals who own their homes directly are treated unfavorably compared with those who buy homes through corporations.

“The previous owner, an unrelated third party, held [the purchased vacation home] in a subchapter S corporation,” the statement said. “Mr. Koch purchased the stock of the subchapter S corporation. When he liquidated the subchapter S corporation, he incurred a loss of $42 million, which was offset by a gain to the S corporation on the distribution, for a net loss of $33 million. As you know, the tax code allows taxpayers to lawfully deduct losses on investment properties. In this case, the stock of the S corporation was the investment property.”

That statement confirms that Koch paid far more than the market value of the neighboring vacation home he acquired by buying the S corporation, known as Indian Point. And that raises questions about the propriety of taking a deduction for a price that was more than double the market price at the time and triple the value claimed after the deduction, based on the numbers in The Koch Papers.

A big deal

Given the written evidence that Middleton says will show that Koch took a massive tax deduction on a personal residence, it is difficult to fathom any reason the IRS to not reach out to him for more evidence. Even with the massive cuts to tax law enforcement that ProPublica, I and others have documented, the evidence here seems easy to pursue. It’s not like the complex allegations of fraud that Middleton described regarding the transfer of profits untaxed out of the United States and then sending them back, still untaxed, to Bill Koch and the 26 minority owners of Oxbow Carbon.

The IRS, as required by Congress under Section 6103 of our tax code, said it could not comment.

That brings up an interesting connection to the adoption of Section 6103, an anti-corruption law, in 1924.

Before 1924, tax returns were public record. Newspapers carried news items reporting that this and that ultra-wealthy American earned so much and paid so much income tax. But that ended in the wake of the 1920s Teapot Dome scandal.

An ironic twist

The 1924 law has a connection to Bunny Mellon’s father-in-law, banking and oil magnate Andrew Mellon. He served as Treasury secretary under three successive Republican presidents. And Mellon was accused by some in Congress of being a tax cheat, which he denied. So the law that gives tax confidentiality to the transactions in which Koch took deductions on a personal residence shields him from public knowledge of the way he handled his transaction with the relative of the man whose conduct played a major role in inspiring the law.

The 1924 law introduced two significant changes to our federal tax code were then enacted by our Congress.

It modified Section 6103 to make tax returns private, a huge boon to tax cheats unless the IRS is well financed to audit returns, which it is not. Under federal law, if an utterly fraudulent tax return is filed but not audited, it’s accepted. That means dishonest tax returns are accepted as filed and the tax thief gets away with his or her crime. Thanks to tax confidentiality, who but insiders would ever know?

Congress also granted itself the same power the president had to examine any tax return on written request. That is what Trump, whose campaign received more than $1 million of donations thanks to Koch, is fighting in ordering the IRS to not turn over six years of his returns to the House Ways and Means Committee chairman.

As I tell my Syracuse University College of Law students, anti-corruption laws can end up fostering corruption because every legal sword can be fashioned into a legal shield. Not only should the IRS and the Massachusetts Department of Revenue investigate, but Congress should also examine whether it needs to overhaul Section 6103.

Shares