"When the going gets tough, the tough get arty." This was the introduction to the inaugural issue of the Arlington Public Library's "Quaranzine," a zine of art, poetry, comics, photos, and short fiction reflective of current life in the surrounding community amid the novel coronavirus pandemic.

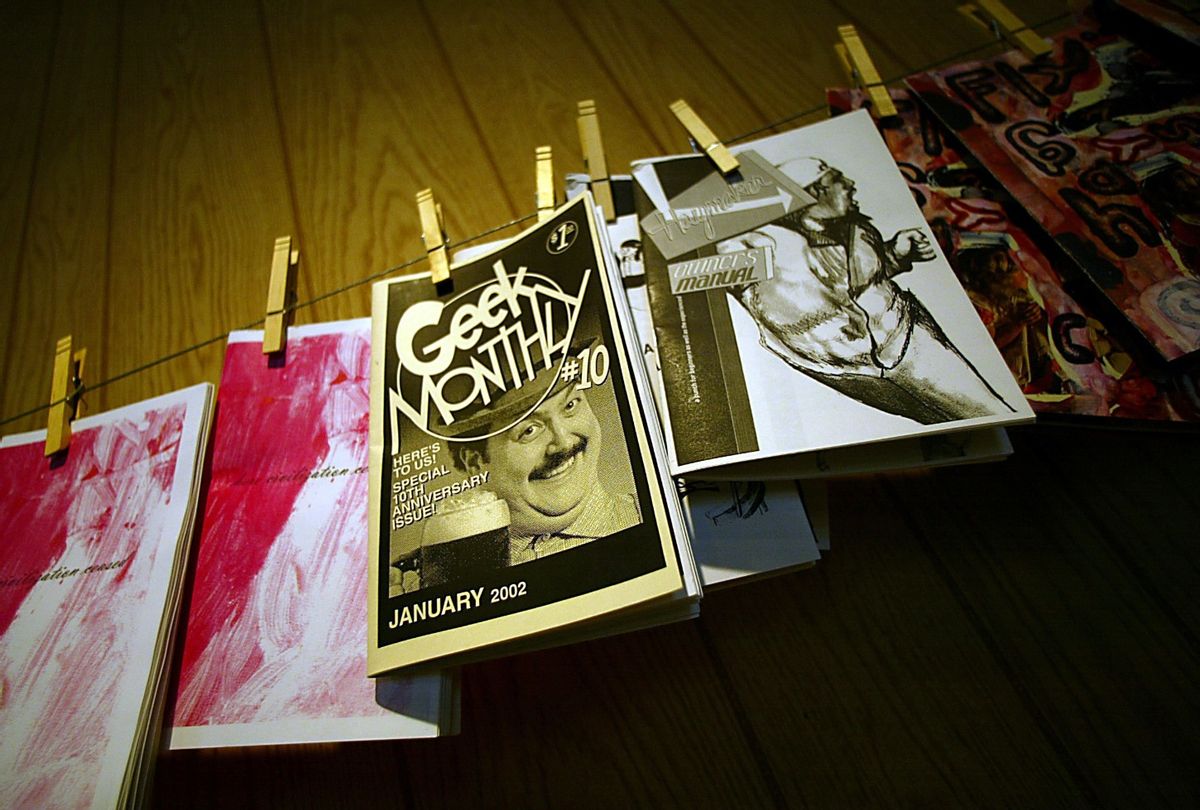

"Zines, popular from the 1980s through the early 1990s, are small publications created by an individual or group. Handwritten, photocopied, hand-drawn, collaged, they can boast a DIY aesthetic or be highly stylized and released digitally," wrote library director Diane Kresh. "'Quaranzine' will likely be a mix of both."

Launched in April, the library's "Quarazine" now has 10 issues (as well as a few special editions covering topics such as confronting racism and kids' issues). Each of them have titles that are affirming and upbeat, like "Keep Hope Alive" and "Holding Steady."

"I hate to use phrases like the 'new normal' because there is nothing about this situation that is normal," Kresh wrote in the introduction to the first issue. "It just is. Our hope is that 'Quaranzine' will make what 'is' a little easier. For all of us."

Kresh isn't the only person with that hope; all across the country, artists and amateurs are creating their own "quaranzines" to reflect the ways in which they see the current reality, and as a way to assert that creating and consuming art remains a balm in troubled times. It's an extension of the urban homesteading and maker movement that has dominated the pandemic aesthetic — just swap out sourdough starter for a pack of colored pencils.

Plus, it's something to take up time now that all our days seem to run together.

Searching the hashtag #quaranzine on social media returns thousands of results. There are artful contemplations on naps, like Daniella Napolitano's "40 Winks," and zines that reflect on our natural world like John Fellows' "Mountains I Have Known" and Sheri Roloff's "The Golden Hour." Some of the zines are very of the moment, like Bianca Mabute-Louie's "Woes of Online Teaching" and Debbie Bamberger's "The Zooms in my Life," while others are a little more whimsical, like Kirk Reedstrom's "I Am (dressed as) Batman, A Day in the Life."

Libraries, community centers and independent publishers all across the country have started hosting online zine-making courses. There are even zines dedicated to teaching readers how to make zines. Some of the creators are professional artists and designers, but the quarazine movement has also captured the attention of newcomers to crafting, like Ciara McClaren, the co-author of the "Quarantine Prom Queen Dream Zine."

"I was aware of zine culture and thought it was one of the things that was a little too cool for me to actually participate in," McClaren jokes. "But the pandemic was the horrifying suspension of time that made things seem possible that weren't in the past."

This was true literally, Mclaren said. Her job as a teacher shifted during the pandemic, so she was no longer going into a physical classroom.

"And in more spiritual terms, I felt this almost suspension of reality that made it a lot more doable to work on this thing," she said.

McClaren, who collaborated on the zine with her two sisters, said they came up with the name first and then wrote content to fit it: an interview with a would-be prom queen, illustrated quarantine dreams and "choose your fighter: prom date edition." The result is earnest, funny and a little surrealistic.

McClaren and her sisters plan on releasing more content digitally, but made the intentional choice to keep their zine free (though readers do have the option to donate an amount they see fit).

"I do think that the pandemic has many people reexamining capitalism, and on a more personal level, the pandemic has people reexamining how much of their time went to work that didn't sustain them, alienation from labor, and all that jazz," McClaren said. "That is definitely a feeling I experienced creating the zine, really feeling sustained by my work and not in a way that had anything to do with money."

But for some professional artists, like Leslie Barlow, creating a quaranzine was an ideal way to tap into their creativity while also making up a noticeable loss in gallery show profits during the pandemic. Barlow is a Minneapolis-based portrait artist whose oil paintings examine "racial identities through decolonizing and healing our collective understanding of belonging and what it means to be family."

She said that she experienced some symptoms of depression early into the pandemic, especially as she was trying to figure out what it meant to be a portrait artist when she couldn't physically be in the same space as her subjects. In response, she started creating portraits via Zoom and Google Hangouts.

The resulting collection was titled "Portraits During a Pandemic," but with gallery spaces still closed, she had nowhere to display them. That's what sparked the idea for her zine, "Connection Unstable."

"I was like, 'Well, it would be really wonderful if I could actually share this with people beyond the digital space,' because we were always online at that point," she said. "I wanted to have that physical experience again, so the zine idea was perfect for that."

Barlow and photographer Ryan Stopera printed 50 copies of the 68-page zine, priced at $28 apiece. Within a few weeks, they were all sold out.

With an uncertain future for gallery spaces, Barlow is looking into getting an art book funded — or maybe even just another zine.

"Especially for people who can't physically be in those [gallery and museum] spaces, how do you still allow them access to that world?" Barlow said. "I think print material is a great way."

Shares