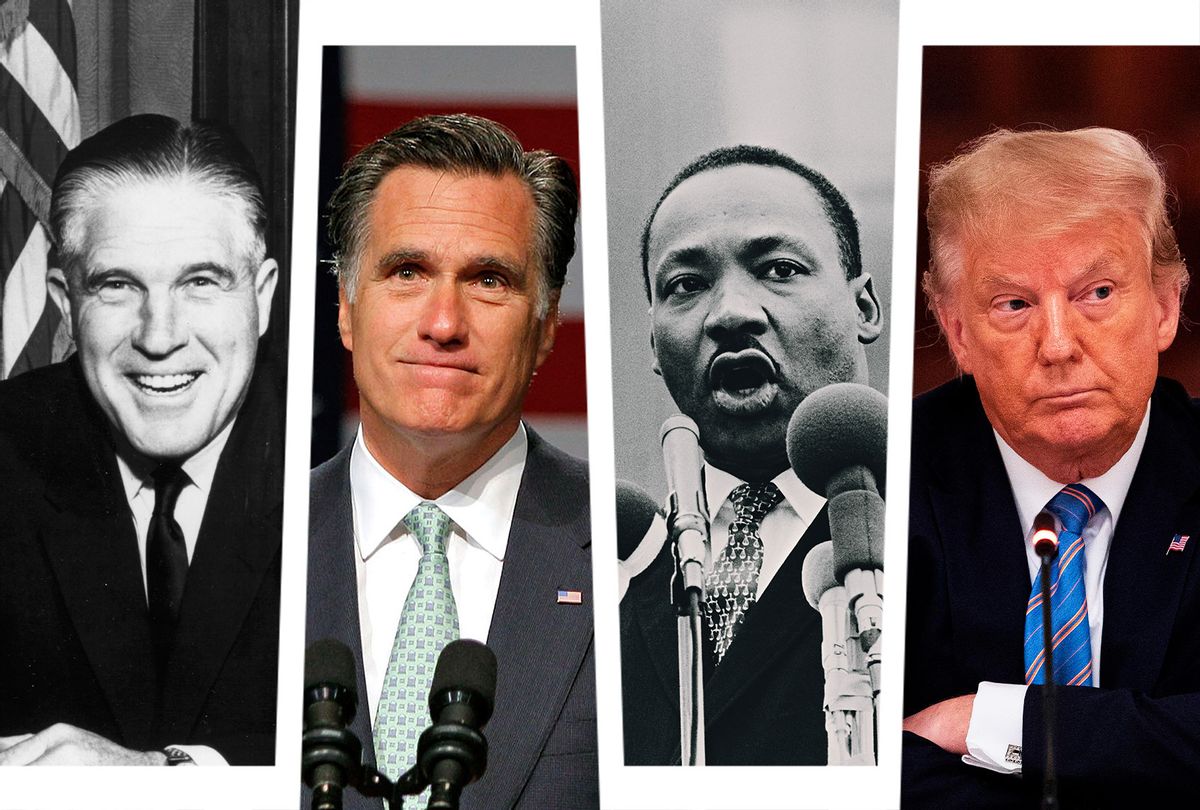

Once upon a time a very long time ago (in the late 1960s), the Republican Party had a moderate and competent Midwestern governor some thought could become their presidential nominee.

He was a prosperous businessman with a reputation for bipartisanship, was impeccably honest and (according to polls) had a good chance of winning a general election. While these things rarely matter in terms of political strategy discussions, he also would have broken a historic barrier by becoming America's first Mormon president (which we still have not had). As it happens, this man was also on the right side of history when it came to key issues like civil rights and the Vietnam War — another consideration that may not matter to strategists, but does to historians.

Yet George W. Romney made a mistake. At one point while discussing the Vietnam War, he offhandedly used the term "brainwash" to describe how he had been treated by policymakers. The press, which already thought Romney was prone to embarrassing himself, deemed that word choice to be both hilarious and disqualifying. Before he knew it, he was dealing with a PR nightmare (some claimed to be offended by the remark, some ridiculed him, etc.) and his 1968 candidacy — which had already been struggling — became a punchline. The Republicans instead nominated Richard Nixon, who was eventually elected and appointed Romney as his secretary of Housing and Urban Development. Before long the controversy was mostly forgotten, particularly the fact that Romney had only used that word to describe how President Lyndon Johnson's officials were lying to the American people about the war. As pundits indulged themselves in a frenzy of self-righteous snark, they conveniently ignored that Romney had been right. Like many other Americans, he had initially supported Johnson's policies because he had been misled.

America may well owe George Romney something of an apology, as well as an acknowledgment of the ways his son, Sen. Mitt Romney of Utah, is or is not carrying on his father's legacy.

"George Romney was unlike any other politician," Rick Perlstein, the American historian and journalist who has penned acclaimed books on the 1960s and 1970s like "Before the Storm" and "Nixonland," told Salon. He described Romney was independent-minded and even to the left of some Democrats on certain issues. "His remarks about Vietnam generally, running for president in 1967 and early 1968, were absolutely prophetic," Perlstein explained. "We're talking more what someone like Robert F. Kennedy] was saying than what Hubert Humphrey was saying — how it was colonialist. He had this prophetic mode, which was really unique among politicians, and spoke his truth in a way that was quite brave."

Romney's stances against right-wing extremism in his party stand out the most. Romney was a tireless advocate for civil rights (and was attacked by some fellow Latter-day Saints for this) and made it clear that Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was welcome in Michigan when King arrived to protest racial discrimination. Romney insisted, in speech after speech, that race should play no role in determining how a human being is treated by other people. He was horrified when the segregationist Barry Goldwater became the Republican nominee in 1964, and refused to back him.

George Romney's legacy is not without controversy. (Keeanga-Yamahtta Taylor has criticized Romney's policies as a Nixon cabinet official.) But he was described by Pulitzer-winning historian Theodore H. White as having "a sincerity so profound that, in conversation, one was almost embarrassed." Furthermore, a political figure does not need to be perfect to receive credit for courage. Indeed, the notion that we must always add caveats to any praise we offer a person from "the other side" is symptomatic of a much bigger problem in American politics.

This brings us to Mitt Romney.

You may already know that the trajectory of the younger Romney's career mirrored his father's: Success in business, serving as governor in a non-Western, non-Mormon state (Massachusetts instead of Michigan), presidential campaigns (unlike his father, Mitt won the Republican nomination, but lost to Barack Obama in the 2012 general election) and then election to the Senate from Utah.

In an email to Salon, Mitt Romney discussed his father's influence. "I saw in my father a person without guile," the senator observed. "He acted from principle, not politics. He was a man driven by what he thought was right and did not worry about the consequences. His commitment to civil rights put him ahead of his time. Throughout my personal and political life, I have tried to live by the example he set."

Perlstein does not agree that Mitt Romney has lived up to his father's example, and referred back to what he wrote in a 2012 article for Rolling Stone.

Mitt learned at an impressionable age that in politics, authenticity kills. Heeding the lesson of his father's fall, he became a virtual parody of an inauthentic politician. In 1994 he ran for senate to Ted Kennedy's left on gay rights; as governor, of course, he installed the dreaded individual mandate into Massachusetts' healthcare system. Then he raced to the right to run for president.

Perlstein raises legitimate criticisms of Romney's policies and philosophy, and his chameleonic ability to say different things to different audiences (once describing himself as "severely conservative" during the 2012 campaign). But on at least one point, I disagree.

"I think Mitt Romney and Donald Trump are bad and dangerous in different ways," Perlstein said. "I think Mitt fits into this tradition where you only dip into enough demagoguery to maintain your political respectability, and Trump is more in a tradition where you blow through respectability and go into pure demagoguery." Speaking about Romney's potential role in his party, he added, "I'm cynical of a lot of Never Trumpers. I think a lot of them have placed a strategic political bet that Trumpism collapses and they can inherit the ruins of the Republican Party."

I don't think that's entirely fair. Romney has suffered tremendous blowback for his opposition to Trump. He recognized that Trump was a fraud during the 2016 campaign and forcefully called him out on it at the time. He was the only Republican senator who voted to convict Trump twice, and has refused to play along with Trump's Big Lie about the 2020 election. Romney has been consistent and clear in saying that his loyalty is to his principles, not to his party or any individual leader. He has even followed in his father's civil rights-era footsteps by joining Black Lives Matter protesters. Let's give him credit where it's due.

Romney has made no small sacrifice in standing up to the Trumpers. He has been harassed, booed and personally attacked. He must know that if he continues to oppose Trump, things will likely get worse. Trump willingly put his own vice president in physical danger during the Jan. 6 insurrection attempt. He has insulted and belittled other former opponents like Ted Cruz and Lindsey Graham, in the process reducing them to sycophants — because they now see the political danger of crossing him.

Romney is aware of that danger too, but has not backed down. Of course it's legitimate to disagree with Romney's political views, but acts of courage tend to be preserved by historians long after immediate partisan passions have cooled. When that happens, Mitt Romney will likely be remembered as one of the few truly courageous Republicans in the Trump era. In that sense, at least, he's a credit to his dad, who taught him to build bridges between communities instead of burning them down, and to believe that honor matters more than political factionalism.

Shares